Ships in Class

| Ship | Laid Down | Launched | Commissioned | Decommissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

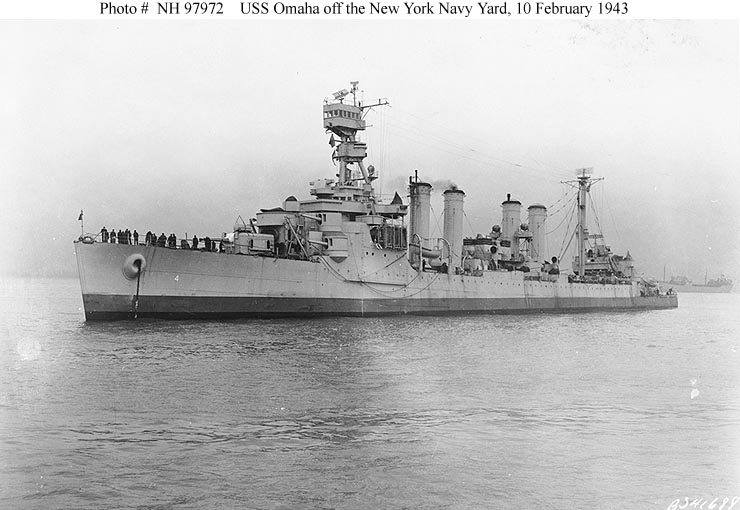

| Omaha (CL-4) | 6 Dec. 1918 | 14 Dec. 1920 | 24 Feb. 1923 | 1 Nov. 1945 | Scrapped Feb. 1946 |

| Milwaukee (CL-5) | 13 Dec. 1918 | 24 Mar. 1921 | 20 Jun. 1923 | 16 Mar. 1949 | Sold for scrap Dec. 1949 |

| Cincinnati (CL-6) | 15 May 1920 | 23 May 1921 | 1 Jan. 1924 | 1 Nov. 1945 | Scrapped Feb. 1946 |

| Raleigh (CL-7) | 16 Aug. 1920 | 25 Oct. 1922 | 6 Feb. 1924 | 2 Nov. 1945 | Scrapped Feb. 1946 |

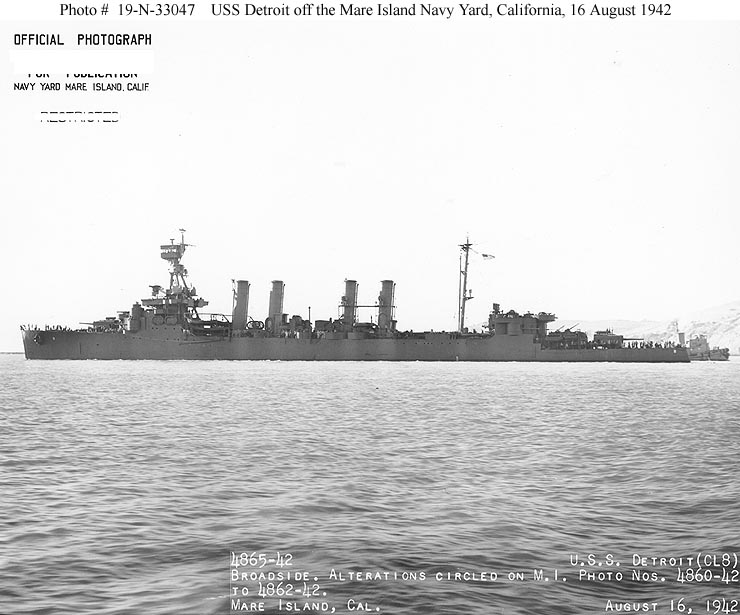

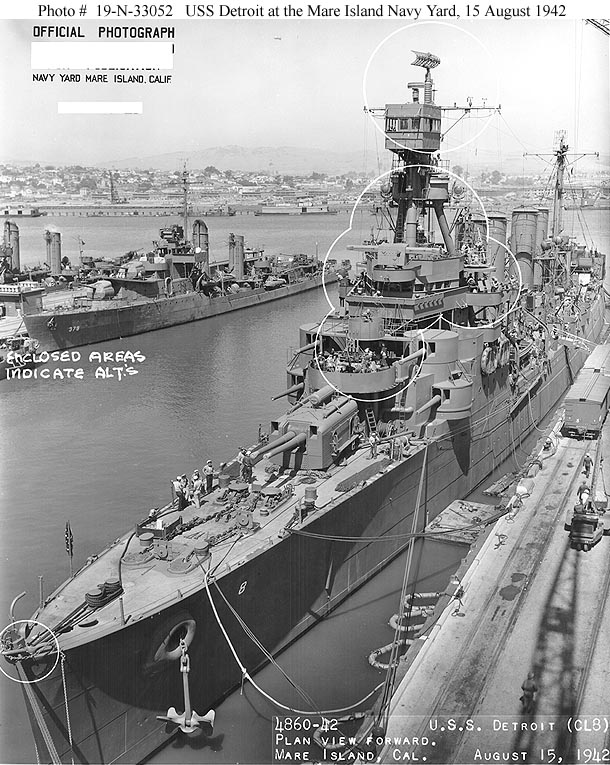

| Detroit (CL-8) | 10 Nov. 1920 | 29 Jun. 1922 | 31 Jul. 1923 | 11 Jan. 1946 | Scrapped Feb. 1946 |

| Richmond (CL-9) | 16 Feb. 1920 | 29 Sept. 1921 | 2 Jul. 1923 | 21 Dec. 1945 | Sold for scrap Dec. 1946 |

| Concord (CL-10) | 29 Mar. 1920 | 15 Dec. 1921 | 3 Nov. 1923 | 12 Dec. 1945 | Sold for scrap Jan. 1947 |

| Trenton (CL-11) | 18 Aug. 1920 | 16 Apr. 1923 | 19 Apr. 1924 | 20 Dec. 1945 | Sold for scrap Dec. 1946 |

| Marblehead (CL-12) | 4 Aug. 1920 | 9 Oct. 1923 | 8 Sept. 1924 | 1 Nov. 1945 | Sold for scrap Feb. 1946 |

| Memphis (CL-13) | 14 Oct. 1920 | 17 Apr. 1924 | 4 Feb. 1925 | 17 Dec. 1945 | Sold for scrap Dec. 1947 |

Characteristics

- Displacement: 7,050 tons (standard)

- Dimensions: Length 550.5 feet, beam 55.4 feet, draft 20 feet

- Speed: 34 knots

- Propulsion: 4x Westinghouse reduction-geared turbines (4 shafts), 12 Yarrow boilers, 90,000 shp

- Range: 10,000 nm at 15 knots

- Protection: belt 3 inches, deck 1.5 inches, turret 2 inches

- Crew: 458 (peacetime)

Armament

*The following list does not represent any single ship at any given time. The armament on these ships changed over their service life. Some of the 6″ guns and 21″ torpedo tubes were removed while the AA armament frequently changed in caliber and was increased.

- 12x (later 10x) 6″/53 guns (4x in twin turrets, 8x in single casemates)

- 2x (later 8x) 3″/50 AA guns

- 2x 3-pdr. guns

- 8x 0.5″ machine guns

- 12x 28mm/75 machine guns

- 8x 20mm machine guns

- 6x 40mm AA guns

- 10x (later 6x) 21″ torpedo tubes (in 2 twin and 2 triple mounts)

Design

At first glance, the Omaha cruisers bear a striking resemblance to the 4-stacked Clemson-class destroyers they were designed to lead. U.S. naval construction prior to World War I emphasized battleships, battlecruisers, and scout cruisers. Subsequent reports on the Battle of Jutland seemed to indicate that battlecruisers were overrated. That being said, on 29 August 1916, the Senate authorized a three-year building program from FY 17-19. This building program included 10 battleships, 6 battlecruisers, and 10 scouts. These scouts were to become the Omaha-class light cruisers (Friedman, 1984, p. 72).

Around the same time that the General Board was considering designs for its battlecruisers, it laid down characteristics for the scout cruisers in December of 1915. The Board called for a cruiser with a displacement of about 8,000 tons, a speed greater than 30 knots, an endurance of 10,000 nautical miles, and a battery of ten 6” guns (arranged for maximum end-on-fire), four AA guns (two heavy and two automatic), and two above-water torpedo tubes on each side. Additionally, it was to carry four aircraft. For armor, the design was to include 3” over the belt and 1.5” over the deck to cover the machinery spaces. The chosen design described the Omaha cruisers as a “big destroyer” with a displacement of 6,750 tons, a length of 550 feet, a beam of 51 feet, and a draft of 26 feet (Friedman, 1984, p. 76-77).

The unique fitting of dual-turret and single casemate guns was born out of the requirement for a maximum end-on and broadside fire arrangement. In this configuration, six guns could be fired directly ahead or astern while eight could be presented in a broadside (Hore & Ireland, 2010, p. 437). The placement of the main armament was debated and the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) even proposed a design that would have four twin gun mounts on the centerline. However, the General Board was skeptical of such an arrangement since it viewed centerline armament as more useful on capital ships rather than on scouts. Whereas capital ships were expected to fight in line-ahead formation, scouts would have to deal with attacks from multiple directions simultaneously. Eventually, the cruisers would be completed with two twin mounts on the centerline in addition to their four broadside casemated guns (Friedman, 1984, p. 79).

In service, the twin 6”/53 gun was cramped and did not fire as quickly as two single guns. The two lower, after broadside guns, were also found to be impossible to operate, even in moderate weather. By 1928, alterations to the Omaha-class included a reduction in the number of guns, on most of the ships this meant the lower, after guns. By 1939, Marblehead had ten guns and only CLs 4, 5, 10, 11, and 13 had retained all twelve guns (Friedman, 1984, p. 84).

The Omaha cruisers were envisioned to carry a sizeable number of torpedoes, but the storage of reloads was considered hazardous. Moreover, in January 1920, the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) opined that no reloads should be carried because “the opportunity for their use will not arise often, or be known beforehand. …In battle there will be no chance to reload… and in [most types of weather] loading torpedoes would be extremely dangerous, or at any rate quite impracticable.” Ultimately, it was decided to equip them with a total of ten torpedoes in two triple mounts and two twin mounts (Friedman, 1984, p. 80).

Following favorable tests on destroyers, CLs 7-13 were fitted with hydrophones housed in 30-foot blisters positioned roughly between frames 10 and 18 on each side (Friedman, 1984, p. 80).

The original AA battery of two 3”/50 guns was increased to four during construction. In 1938, the Concord was fitted with two more 3”/50 guns on her centerline aft while at Mare Island. These were considered useful because they could fire from right astern to well forward of the beam. Earlier, in 1933, the Trenton was fitted with machine guns for defense against dive bombers (Friedman, 1984, p. 84).

Already a packed design, they turned out to be badly overloaded. They drew 2 feet more than their designed figure and tended to heel over sharply when turning. This often flooded the main deck twin torpedo mounts. By 1924, all the COs of these ships and the Board of Inspection and Survey asked that the twin tubes be landed. The growth of the ship’s complement from 330 to 425 also led to proposals for increased living space. Approved changes from the General Board included crew space housing in the after upper deck around the 6” guns, moving the galleys from the main deck to the upper deck, removing the mine stowage tracks between frames 112-120, and converting some of the warrant officers’ mess spaces to crew accommodations. The main deck torpedo tube ports were sealed off, and the mine tracks for the 224 mines were landed, although the capability to lay mines remained (Friedman, 1984, p. 80).

Comparisons between the Omaha cruisers and pre-WWI British cruisers such as the “C” class were favorable with the Omahas possessing significantly greater endurance, speed, and armament layout. Further development of the Omaha-class was halted with the U.S. entry into WWI and especially with the passing of the Washington Naval Treaty in 1922 which would usher in the various treaty cruiser designs (Friedman, 1984, p. 105).

In 1924, C&R admitted that these ships could not be made comfortable in light of the size and heat that the machinery gave off. In 1929, a report by the CinC U.S. Fleet mentioned that the Omahas were poorly insulated, too hot in the tropics, and too cold in the northern latitudes. Specifically, the absence of wood decks and awnings as well as the lack of slop chutes and scuppers made the ships uninhabitable and filthy in warm climates or during the summers. The uncovered steel decks were unbearably hot. C&R noted that toilet arrangements were unacceptable with 1 head for 24 men compared to 1 per 16 as designed (Friedman, 1984, p. 80).

Despite their issues, the Omahas were described as good seaboats. But, even at moderate speed and in moderate seas, the fore and aft broadside gun compartments would flood with spray and the torpedo compartments would flood with green water. There were complaints that the steering engines were not powerful enough, but the tactical diameter was satisfactory. The hulls had a tendency to leak and at high sustained speeds, the oil tanks would become contaminated with seawater. In one instance, Richmond, steaming at 25 knots, lost power for 30 minutes (Friedman, 1984, p. 80).

Upon their commissioning, the Omahas were the last broadside cruisers in the world. When completed, they were the fastest cruisers in the U.S. Navy (Terzibaschitsch, 1984, p. 36). Although designed as scouts, they spent the interwar years leading destroyer flotillas (Friedman, 1984, p. 80). Tactical scouting became the purview of cruiser aircraft and distant scouting was conducted by heavy cruisers of the scouting force. Thus, the distinction between screening and scouting that had been integral to the design of the Omahas was now irrelevant (Friedman, 1984, p. 84).

Possible Conversion to AA Cruiser

In order to get more heavy AA guns aboard ships, C&R proposed in June of 1940 to convert the Omahas to anti-aircraft cruisers. This would have meant all 6” and 3” guns were to be replaced with seven 5”/25 or 5”/38 guns and six quadruple 1.1” guns. Various other proposals were batted around until it was decided that the mounting of 5”/38 guns and the associated directors would have been impossible. In July of 1940, the General Board ordered two of the 3” guns replaced with quadruple 1.1” AA guns and the Omahas converted for anti-aircraft duty. The conning towers were removed and an open bridge structure was built forward of the pilot house. Mk 50 directors were installed to control the 3”/50 mounts and by March of 1942, the AA battery was composed of seven 3”/50s, two quadruple 1.1” (to be replaced by two twin 40mm Bofors), and eight 20mm guns. The main armament was reduced to ten 6”/53s with the lower aft guns removed on Omaha, Milwaukee, Concord, Trenton, and Memphis. Further weight reduction involved the removal of the machine gun platform on the foremast, as well as a reduction in the number of boats and 6” gun ammunition. The ships underwent further armament modifications in 1943, but Cincinnati was unique in that she had two single army-type 40mm guns installed in place of her torpedo tubes. By 1944, it was realized that little could be done to significantly improve the AA armament of these cruisers given their age (Friedman, 1984, p. 341 – 343).

Operational Histories

*I’ll just be covering some highlights from certain ships in the class.

For the most part, the Omahas went through WWII in secondary roles, such as performing patrol duties in the South Atlantic, the Caribbean, and around South America (Friedman, 1984, p. 315).

Omaha (CL-4)

Omaha spent much of the interwar period conducting fleet exercises in the Caribbean and patrolling off the western coast of the United States.

While conducting Neutrality Patrols in the Atlantic on 6 November 1941 with the destroyer Somers (DD-381), she intercepted the German blockade runner Odenwald. After seizing the cargo of nearly 4,000 tons of rubber, members of Omaha‘s boarding party were each awarded $3,000 by the U.S. government several years later. This would be the last time that prize money was awarded to a U.S. Navy ship.

Omaha would spend the next several years conducting convoy escort duties and interdicting German blockade runners in the South Atlantic between the coasts of Brazil and West Africa. She largely operated out of the port of Recife, Brazil.

From 18 – 20 May 1942, Omaha assisted in the salvage of the Commandante Lyra which had been torpedoed by the Italian submarine Barbarigo. After locating the Commandante Lyra, Omaha‘s salvage team managed to save the ship allowing her to be towed back to Fortaleza, Brazil.

On 1 June 1942, Omaha rescued 40 survivors from the torpedoed Charlbury.

On 4 January 1944, Omaha and Jouett (DD-396) sank the German blockade runner Rio Grande. The Marblehead would later rescue 72 survivors. The very next day Omaha would sink the German blockade runner Burgenland in the same area where she encountered the Rio Grande.

On 6 February 1944, while patrolling with Jouett and Memphis, Omaha rescued survivors from U-177 which had been sunk by a PB4Y-1 Liberator from Ascension Island.

On 4 July 1944, Omaha departed for the Mediterranean Theater. She assisted in several bombardments during the invasion of southern France before returning to the South Atlantic in September. She would spend the next 10 months performing escort duties.

On 8 July 1945, she assisted in the search and rescue of the Brazilian cruiser Bahia (C.12) which had reportedly been torpedoed by a submarine. However, an investigation determined that one of Bahia‘s gunners had accidentally fired into a rack of depth charges during an anti-aircraft gunnery exercise.

Omaha returned to the U.S. in August and was decommissioned on 1 November 1945.

Milwaukee (CL-5)

Milwaukee spent the interwar years cruising the Pacific and the Caribbean. She assisted Omaha in the salvage of Commandante Lyra in May of 1942.

On 21 November 1942, she, along with the cruiser Cincinnati (CL‑6) and the destroyer Somers (DD‑381), intercepted the German blockade runner Annaliese Essenberger which was masquerading as a Norwegian vessel. Giving chase, the crew scuttled the ship before they caught her. Milwaukee took 62 prisoners aboard.

She patrolled the South Atlantic until February 1944. In late February and early March, she escorted a convoy to Ireland. Later that month, she provided escort for convoys headed to Murmansk and Archangelsk. On 20 April 1944, she was transferred to the Soviet Navy under Lend-Lease and commissioned as the Murmansk. She would continue convoy escort duties in the Atlantic for the remainder of the war until being transferred back to the U.S. on 16 March 1949 when she was decommissioned.

Raleigh (CL-7)

During the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Raleigh was moored at berth F-12, on the east side of the north channel. In the first attack wave, a torpedo hit Raleigh port side amidships. The explosion tore through her number 2 boiler room. Both the forward boiler rooms and the forward engine room flooded. Additionally, a bomb from a dive bomber hit her aft, passed through three decks, missed her aviation gas tanks, and exploded in the water 100 yards from her. Thanks to the hard work of the crew who pumped out the water and jettisoned a great deal of topside weight, the ship was saved. Indeed, BuShips believed that the ship would have been lost (Friedman, 1984, p. 314). Amazingly, only a few were wounded.

After some repairs, she departed Pearl Harbor on 21 February 1942 for Mare Island. Following further repairs and overhaul, she spent the rest of 1942 escorting convoys around the Pacific and searching for enemy picket ships. From November 1942 she began patrolling Alaskan waters around Dutch Harbor and Kiska. On 2 August, she participated in the bombardment of Kiska.

In February 1944 she would also bombard positions in Kurabu Zaki, Paramushiru, and the Northern Kuriles. The remainder of her career was fairly uneventful. She was decommissioned on 2 November 1945.

Detroit (CL-8)

Like the Raleigh, Detroit was present at Pearl Harbor during the Japanese attack. However, she was able to get underway and contribute to the anti-aircraft defense of the harbor. After the attack, she searched the western shore of Oahu for possible Japanese landings and then for any retiring Japanese forces.

In the following days, she escorted convoys between Hawaii and the West Coast. On one such journey, she carried 9 tons of gold and 13 tons of silver from the submarine USS Trout (SS-202) that had been evacuated from Corregidor following the Japanese invasion of the Philippines. She delivered the bullion to the Treasury Department in San Fransisco.

On 10 November 1942, Detroit sailed for Kodiak, Alaska to become the flagship of TG 8.6 which patrolled between Adak and Attu to prevent further Japanese seizure of the Aleutians. In April and May of 1943, she supported the capture of Attu and then in August, she bombarded Kiska. However, the Japanese had already evacuated the island.

In June of 1944, she bombarded installations in the Kuriles with TF94. In February 1945, she served as flagship for the replenishment group of the 5th Fleet at Ulithi. She would continue to oversee replenishment operations following the end of the war and was decommissioned on 11 January 1946.

Richmond (CL-9)

On 7 December 1941, Richmond was en route to Valparaiso, Chile. She was recalled and patrolled off Panama to escort convoys coming in from the Society and Galapagos Islands.

In January 1943, she headed for the Aleutians where she became the flagship of TG16.6 which defended the approaches to Amchitka. Later she would participate in the bombardment of Attu.

On 27 March 1943, the Japanese mounted an attempt at resupplying the Aleutian islands. Three transports were escorted by the heavy cruisers Nachi and Maya, the light cruisers Tama and Abukuma, and the destroyers Wakaba, Hatsushimo, Ikazuchi, and Inazuma. In contrast, the American force was composed of the heavy cruiser Salt Lake City, the light cruiser Richmond, and the destroyers Coghlan, Bailey, Dale, and Monaghan. Sending the transports and one destroyer ahead, the Japanese and Americans were about to make contact.

About 180 miles west of Attu and 100 miles south of the Komandorski Islands, the two forces met. While the Richmond was initially fired upon, the Japanese shifted their fire to Salt Lake City. In a running battle, Salt Lake City was disabled and dead in the water. Richmond assisted her while the American destroyers closed on the Japanese for a torpedo attack. The Japanese, low on fuel and ammo, failed to realize that they outgunned the American force and turned west to retreat. The Japanese transports similarly turned back before reaching Attu. While the battle was tactically inconclusive, the Americans had succeeded in preventing the Japanese from resupplying Attu which was retaken in May.

In July, Richmond participated in the pre-invasion bombardment of Kiska, only to later discover the island abandoned. After a brief refit at Mare Island, Richmond continued to patrol the Aleutians for the remainder of the year.

In February 1944 she bombarded installations in the Kuriles and conducted antishipping patrols for the rest of the war. She was decommissioned on 21 December 1945.

Trenton (CL-11)

From June 1939 to May 1940, Trenton patrolled around the Mediterranean and off the coast of the Iberian Peninsula to protect U.S. interests during the Spanish Civil War. During her return home, she carried Luxembourg’s royal family which was fleeing the Nazis at the time.

From 1941 to mid-1944, she operated as part of the Southeast Pacific Force. During this time she escorted convoys and patrolled off the western coast of South America between the Panama Canal and the Strait of Magellan.

In July 1944, Trenton headed north for duty in the Aleutians. She made several patrols to the Kuriles and bombarded Paramushiru on 3 January 1945 before resuming patrols around Alaska for the remainder of the war. In 1945, she periodically made patrols to the Kuriles to bombard Paramushiru and Matsuwa. She was decommissioned on 20 December 1945.

Marblehead (CL-12)

In 1938, Marblehead was assigned to the Asiatic Fleet in Cavite, Philippines. She patrolled around the Sea of Japan and the South and East China Seas as tensions rose in Asia.

Upon the outbreak of the Pacific War, Marblehead joined with the Royal Netherlands Navy and Royal Australian Navy ships to cover Allied shipping withdrawing from the Japanese invasion of the Philippines. On 24 January 1942, Marblehead covered the withdrawal of a Dutch and American force that had attacked a Japanese convoy at Balikpapan.

Later, on 4 February 1942, while attempting to interdict further Japanese forces in the Makassar Strait, the force was attacked by 36 Japanese bombers. Although managing to evade several waves, Marblehead was hit by two 100 kg bombs. One struck aft near her steering gear and the other hit her between the bridge and fore funnel. Oil fires broke out and were extinguished, but her rudder jammed causing her to perpetually circle to port at 25 knots for three hours, during which she heeled over to starboard. Additionally, a near miss off the bow ruptured the hull plating and caused significant flooding in her bow which meant that the ship had to be re-trimmed by removing oil in order to maneuver (Friedman, 1984, p. 314).

The crew managed to get her rudder back to 9 degrees left and steer her by varying the speed of the engines. The damaged Marblehead then began a more than 16,000-mile journey back to New York via Ceylon, South Africa, and Brazil, making intermittent repairs along the way. She finally arrived at Brooklyn Navy Yard on 4 May after a nearly 3 month-long journey where she went directly into drydock (Rickard, 2014).

On 15 October 1942, the repaired Marblehead joined the South Atlantic Force and operated from Recife and Bahia, Brazil. She then operated in the North Atlantic on convoy duty from February to July of 1944 after which she sailed for the Mediterranean to support Operation Anvil. From 15 – 17 of August, she bombarded positions around St. Raphael. She later returned to the U.S. and was decommissioned on 1 November 1945.

Summation

Throughout World War II, the Omaha-class was found to be lacking in effective AA fire control despite the increase in AA armament. The subdivision was also poor and the low freeboard and fine run meant that the ships possessed little reserve buoyancy (Hore & Ireland, 2010, p. 437). Given their already overloaded state, several ships had their catapults removed and the class did not receive much in the way of modernization. However, the AA armament was increased with the mounting of 20mm and 40mm guns and radar. No Omaha cruisers were lost during the war (Terzibaschitsch, 1984, p. 36).

Evaluation

Ultimately the Omaha-class cruisers were relics of an era when cruisers still acted as the scouting eyes of the battle line. It has been noted that the Omahas were not designed with the same level of subdivision as newer cruisers, indeed they lacked watertight bulkheads above the main deck. Their age and riveted construction, not to mention poor anti-aircraft fire control, were also factors that worked against them. No other U.S. cruisers suffered so badly from such small bombs. The survival of these ships is therefore a testament to the determination of their crews (Friedman, 1984, p. 314-315). By the time World War II ended, these vessels were of a completely obsolete design.

References

Friedman, N. (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Hore, P. & Ireland, B. (2010). The World Encyclopedia of Battleships & Cruisers. London, UK: Anness Publishing.

Naval History and Heritage Command (2015, Jul. 6). Detroit IV (CL-8). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/d/detroit-iv.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, Aug. 10). Milwaukee III (CL-5). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/milwaukee-iii.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, Aug. 26). Raleigh III (CL-7). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/r/raleigh-iii.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2015, Aug. 31). Richmond IV (CL-9). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/r/richmond-iv.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2016, Dec. 26). Marblehead III (CL-12). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/m/marblehead-iii.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2018, Jan. 27). Omaha II (CL-4). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/o/omaha-ii.html.

Naval History and Heritage Command. (2019, Jun. 11). Trenton II (CL-11). Retrieved from https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/t/trenton-ii.html.

Rickard, J. (2014, Jan. 30). USS Marblehead (CL-12). Retrieved from http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_USS_Marblehead_CL12.html.

Terzibaschitsch, S. (1984). Cruisers of the US Navy 1922-1962 (H. Erenberg, Trans.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

Very nice write up, Tim! The Omahas are an interesting design. An AA conversion where all the 6″/53 were removed and replaced with 5″/38 would have solved many of their problems, but probably not worth the expense on such old hulls. That would be fun to model as a “what if”.

LikeLike

It sounds like the Omaha class were not very comfortable for their crews.

LikeLike