Ships in Class

| Ship | Laid Down | Launched | Commissioned | Decommissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamilton (WHEC-715) | Jan. 1965 | 18 Dec. 1965 | 18 Mar. 1967 | 28 Mar. 2011 | Transferred to the Philippine Navy 13 May 2011 (BPR Gregorio del Pilar (PF-15)) |

| Dallas (WHEC-716) | 7 Feb. 1966 | 1 Oct. 1966 | 26 Oct. 1967 | 30 Mar. 2012 | Transferred to the Philippine Navy 22 May 2012 (BPR Ramon Alcaraz (PF-16)) |

| Mellon (WHEC-717) | 25 Jul. 1966 | 11 Feb. 1967 | 9 Jan. 1968 | 20 Aug. 2020 | To be transferred to the Vietnam Coast Guard |

| Chase (WHEC-718) | 15 Oct. 1966 | 20 May 1967 | 11 Mar. 1968 | 29 Mar. 2011 | Transferred to the Nigerian Navy 13 May 2011 (NNS Thunder (F90)) |

| Boutwell (WHEC-719) | 12 Dec. 1966 | 17 Jun. 1967 | 24 Jun. 1968 | 16 Mar. 2016 | Transferred to the Philippine Navy 21 July 2016 (BRP Andrés Bonifacio (PF-17)) |

| Sherman (WHEC-720) | 13 Feb. 1967 | 23 Sept. 1967 | 23 Aug. 1968 | 29 Mar. 2018 | Transferred to the Sri Lanka Navy 27 August 2018 (SLNS Gajabahu (P626)) |

| Gallatin (WHEC-721) | 17 Apr. 1967 | 18 Nov. 1967 | 20 Dec. 1968 | 31 Mar. 2014 | Transferred to Nigerian Navy 7 May 2014 (NNS Okpabana (F93)) |

| Morgenthau (WHEC-722) | 17 Jul. 1967 | 10 Feb. 1968 | 14 Feb. 1969 | 18 Apr 2017 | Transferred to the Vietnam Coast Guard 25 May 2017 (CSB 8020) |

| Rush (WHEC-723) | 23 Oct. 1967 | 16 Nov. 1968 | 3 Jul. 1969 | 3 Feb. 2015 | Transferred to the Bangladesh Navy 6 May 2015 (BNS Somudra Avijan) |

| Munro (AKA Douglas Munro) (WHEC-724) | 18 Feb. 1970 | 5 Dec. 1970 | 27 Sept. 1971 | 24 Apr. 2021 | Transferred to the Sri Lanka Navy 26 October 2021 (SLNS Vijayabahu (P627)) |

| Jarvis (WHEC-725) | 9 Sept. 1970 | 24 Apr. 1971 | 17 Jan. 1972 | 2 Oct. 2012 | Transferred to the Bangladesh Navy 23 May 2013 (BNS Somudra Joy) |

| Midgett (AKA John Midgett) (WHEC-726) | 5 Apr. 1971 | 4 Sept. 1971 | 30 Mar. 1972 | Jun. 2020 | Transferred to Vietnam Coast Guard 1 June 2021 (CSB 8021) |

Characteristics

| Displacement | 2,716 tons (standard), 3,050 tons (full) |

| Dimensions | Length 378 feet (overall), 350 feet (waterline), beam 42 feet 8 inches, draft 20 feet (maximum) (1967) |

| Speed | 29 knots (max sustained), 19 knots (cruising), 11 knots (economical) |

| Propulsion | 2x Fairbanks-Morse 38TD8-1/8-12 12-cylinder diesel engines and 2x Pratt & Whitney FT4-A6 gas turbines in a Combined Diesel or Gas (CODOG) configuration. 2 shafts with controllable pitch propellers; 7,000 shp (on diesels) or 36,000 shp (on gas turbines) |

| Range | 14,000 nm at 11 knots; 9,600 nm at 19 knots; 2,400 nm at 29 knots. |

| Sensors | Radar: 2x SPS-64 (navigation), 1x SPS-29D (1987) (air search); 2x SPS-64, 1x SPS-40B (1990) (air search). Sonar: SQS-38 (1987). |

| Armament | (as designed): 1x 5″/38 (single mount), 2x 20mm/80 (single mounts), 2x 81mm mortars, 2x 0.50 cal MGs, 6x Mark 32 torpedo tubes (in 2 triple mounts) (post-FRAM upgrades): 1x 76mm/62 Mark 75 (single mount), 2x 25mm/87 Mark 38 Bushmaster MGS (single mounts), 1x 20mm Mark 15 Phalanx CIWS, 8x RGM-84 Harpoon AshM (on certain cutters). |

| Crew | 15 officers, 140 enlisted (1967), later increased to 173 total. |

Design

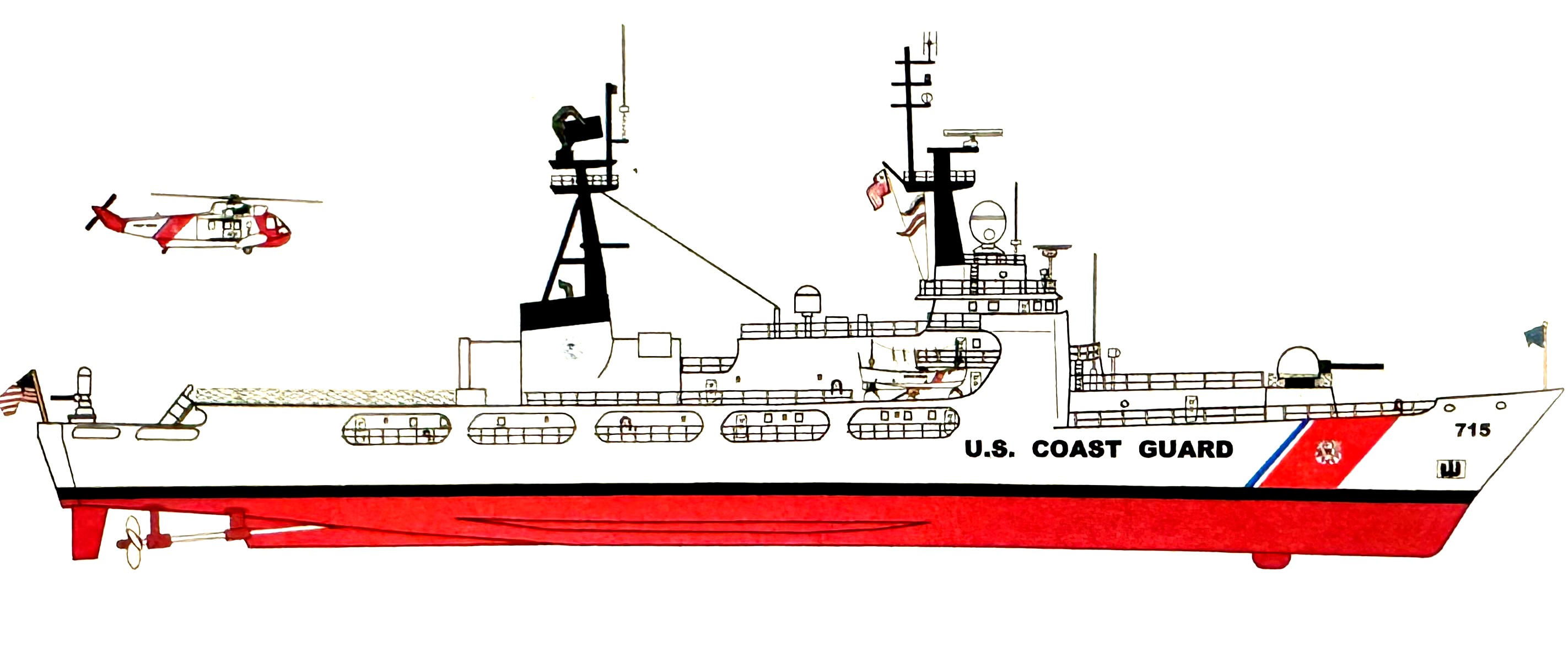

The Hamilton-class cutters were the largest ships in the U.S. Coast Guard, apart from the Polar-class icebreakers and the icebreaker Healy, until they were replaced by the Legend-class National Security Cutters starting in 2008. They are also known as the Secretary-class since most of them are named after Secretaries of the Treasury; however, three of them (Jarvis, Midgett, and Munro) are also called the Hero-class for being named after Coast Guard heroes, although their design is the same as the others. As with other vessels in the Coast Guard, they would also be colloquially referred to by their length, as “378s.”

Between the end of WWII and 1977, the Ocean Station program was ongoing and positioned ships at various points throughout the oceans to provide meteorological and oceanographic data, navigational aids, and rescue sites for vessels and aircraft in distress. This necessitated the need for ships with the ability to remain at sea for extended periods. Since 1944, the U.S. Coast Guard had been relying on converted U.S. Navy warships to satisfy its need for long-range cruising cutters, but in 1965, the Coast Guard adopted the “High-Endurance Cutter” (WHEC) designation, which encompassed vessels that were previously classified as gunboats (WPGs) and small seaplane tenders (WAVPs). Thus, one of the basic design criteria for the Hamilton-class cutters was the ability to conduct sustained operations of 30 days or more at sea to allow them to operate on ocean stations. Designed to be versatile, an additional requirement for the Hamilton-class cutters was to possess the speed and weapons to achieve interoperability with the U.S. Navy. For these reasons, it was envisioned that these cutters were to be used primarily for law enforcement, combat operations, and search-and-rescue duties. While 36 cutters were originally planned for the class, only 12 were built due to the wind-down of the Ocean Station program.1 Although advancements in communications and navigation technology resulted in the termination of the Ocean Station program, the passing of the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act in 1976 set limits on fishing to preserve stocks, and the U.S. Coast Guard was tasked with enforcing these limits. Ships with long-range and high speeds were required for fisheries enforcement, and the Hamilton-class was well-suited for this duty. Subsequently, all but two of the Hamilton-class cutters were shifted to the Pacific Area.2

The Hamilton-class has welded steel hulls and aluminum superstructures. Instead of the U-shaped cross-section favored by the U.S. Navy, the Coast Guard decided to go with a V-shaped hull commonly used by the British. Water tank testing using four 20-foot wooden hull mock-ups showed that these ships could sustain damage and expect to stay afloat for longer than other designs.3 All ships in the class were constructed at Avondale Shipyards in New Orleans, LA. Before the introduction of the U.S. Navy’s Spruance-class destroyers, the 378s were the largest U.S. warships built with gas turbine engines. Improved habitability was factored into the design of these ships with air-conditioned living spaces.4 The Fairbanks-Morse diesel engines have been in continuous manufacture since 1938 and are commonly used in railroad, marine, and industrial applications as power plants. U.S. Navy diesel-electric submarines throughout WWII and the 1950s also used these as propulsion plants, and they continue to be used as backup generators on many nuclear-powered submarines. The Fairbanks Morse 38TD8-1/8 (12-cylinder) diesel engines on the Hamilton-class are larger versions of a 1968 design used in locomotives. The Pratt & Whitney FT4-A6 gas turbines are marine derivatives of the Pratt & Whitney J75 turbojet and are similar to the engines used in Boeing 707 airliners and F-105 Thunderchief jets, although they have no afterburner function.5 Their combined diesel or gas (CODOG) powerplant configuration means that they can run on their diesel engines (each producing 3,400 shp) when cruising at around 17 – 19 knots, or their gas turbines (each producing 18,000 shp) for high speeds of up to 29 knots. However, they cannot operate both diesel engines and gas turbines at the same time. Their screws are 13 feet, four-bladed, inward rotating, and controllable pitch. In addition, the cutters have a 350 hp, 360-degree retractable bow propulsion unit, which aids in maneuvering in restricted waters and in station keeping. The bow propulsion unit can also be used to propel the ship at 5 knots should the main propulsion be disabled.6 WHEC 716 – 723 have synchronizing clutches, while the remaining three have synchro-self-shifting clutches.7 Other specifications indicate that they have a fuel capacity of 732 tons of diesel and 18 tons of JP5 aviation fuel. They have a freshwater capacity of 16,000 gallons with the capability of producing 7,500 gallons/day via evaporators. The ships have three auxiliary power generators producing 500 KW each.8

For research missions, the cutters are equipped with both a wet and a dry laboratory, and an electro-hydraulic winch with a bathythermograph sensor, which can collect oceanographic data on salinity, temperature, and depth. Originally, located between the exhaust stacks and turbine intakes was a weather balloon shelter and an aerological office.9 The balloon shelter could also serve as a “nose shelter” for the amphibious helicopters in use at the time that could land on the 80-foot flight deck.10

For combat operations, the ships have a fully equipped Combat Information Center (CIC) that can serve as an at-sea rescue coordination center, if needed. The originally mounted 5″/38 gun, supplied by the Navy, was controlled by the Mark 56 Gun Fire Control System (GFCS), and her torpedoes could be controlled with the Mark 309 underwater battery fire control system. A closed-circuit television system is installed throughout the ship to allow personnel on the bridge, damage control central, and the two repair lockers to monitor combat operations, flight operations, towing evolutions, engine and machinery spaces, and damage control efforts. A portable video camera can also be connected to this system.11

FRAM upgrades

After 20 years of service, in order to maintain their interoperability with U.S. Navy warships, these cutters went through the Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization (FRAM) program from late 1986 to 1990. WHECs 715, 716, 718, and 721 were modernized at Bath Iron Works in Bath, ME. The rest were modernized at Todd Shipyard in Seattle, WA.12 In general, these changes increased their service life to 44 years and upgraded their gunnery, electronics, and aviation capabilities.13

The structural and internal FRAM upgrades included the following:

- Replacement of numerous structural members and hull plating (given that most of the cutters had been in service for 20 years at the time).

- Removal of both diesel engines and gas turbines, which were sent to their manufacturers to be restored to “like new” condition.

- Restoration or replacement of the emergency gas turbine generator with a standard model across all ships.

- Restoration or replacement of all pumps, compressors, and valves.

- Configuration changes to the fuel tanks and piping. The fuel tanks also received a new coating system.

- Redesign of the HVAC system.

- Installation of an Aqueous Fire-Fighting Foam (AFFF) and HALON system in the machinery

spaces as well as in the newly installed retractable hangar. - Installation of a fuel probe system to aid in at-sea refueling evolutions.

- Relocation of the CIC from the 01 and 02 levels in the superstructure to the third deck within the hull. New berthing areas replaced the now vacated spaces.

- Changing the mainmast to a tripod configuration to support the weight of new sensors and combat systems.

- Extending the deck house forward to provide space for a control booth and loading spaces for the new 76mm gun. (Later known as the gun deck.)

- Reinforcement of the flight deck by eliminating the aftmost rectangular porthole to accommodate heavier helicopters.

- One of the easiest ways of distinguishing the Hamilton-class cutters in their original configuration versus their later FRAM upgrades was the six large rectangular portholes on the ship’s side. The strengthening of the flight deck to accommodate the larger helicopters entering service at the time meant deleting the aftmost porthole.15

- Conversion of the balloon shelter into a retractable hangar on the flight deck to meet requirements for helicopter storage and maintenance.

- The addition of the retractable hangar also reduced the size of the flight deck. The hangar can only accommodate one HH-65 Dolphin helicopter since the HH-60 Jayhawk helicopters are too large and lack folding rotor blades and tail booms to fit inside the hangar.16

- Installation of a glide slope indicator, deck status lights, deck and hangar wash lights, line-up lights, and wave-off lights to aid in helicopter landings.

In addition to overhauling the cutters, the Navy and the Coast Guard agreed to modernize their combat systems and weapons following their FRAM upgrades. In economic terms, it was more cost-efficient for the Navy and Coast Guard to upgrade these 12 cutters with modernized anti-surface and anti-submarine weapons, with the additional benefit of providing a trained crew that could serve as a further force multiplier, if needed. All for the cost of one new frigate.17

Armament and weapons systems upgrades during the FRAM program included the following:

- Replacement of the 5″/38 Mark 30 gun with an OTO Melara 76mm/62 Mark 75 gun, which was more reliable and easier to maintain.

- Replacement of the Mark 56 GFCS with a Mark 92 mod 1 GFCS.

- Upgrading the Mark 32 Torpedo tubes from mod 5 to mod 7.

- Installation of Mark 36 mod 1 Super Rapid-Blooming Offboard Chaff (SRBOC) launchers on the deck aft of the pilothouse.

- Replacement of the AN/SPS-29D Air Search Radar with an AN/SPS-40B (later updated to the

40E). - Upgrading the AN/SPS-64v Surface Search Radar with a collision avoidance system. (This radar was later replaced by the AN/SPS-73)

- Upgrading the Electronics Support Measures (ESM) suite by adding an AN/SLA-10B to the AN/WLR-1C (later upgraded to the WLR-1H).

In total, the FRAM upgrades resulted in about 75% of the shipboard electronics being changed out or modified and one-third of the engineering systems being overhauled or replaced; in addition to reconfiguring the living spaces, flight deck, and changing the weapons systems.18

Post-FRAM upgrades

Following their FRAM upgrades, additional upgrades to the Hamilton-class included the installation of certain weapon systems, which were completed in the early 1990s. These post-FRAM changes included the following:

- Installing a 20mm Mark 15 Phalanx Close-In Weapons System (CIWS) on the stern.

- Removal of the Mark 32 torpedo tubes, AN/SQS-38 sonar, Mark 309 underwater battery fire control system, and the AN/SLQ-25 (NIXIE) torpedo countermeasure system.

- Installing two 25mm Mark 38 Machine Gun Systems amidships in place of the torpedo tubes.

- Installing two quadruple Mark 141 canister launchers with RGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missiles on the gun deck just aft of the main gun. (These missiles were reportedly only installed on five cutters and were removed after the program was canceled in 1992.)

The deletion of their antisubmarine and antiship missile systems was due to the end of the Cold War and the lack of a Soviet naval threat. As such, these weapons systems were deemed unnecessary.19

Operational Histories

Note: I’ll only be covering the histories of these ships based on the information I can verify through official sources. As a result, some of the histories will be quite long, and others may be limited to their service up to 1990, since official information after that time may be sparse, even though all of them served for at least another 21 years. I’m also omitting any time they spent on an ocean station unless it involved a rescue, as well as any service they’ve seen since being transferred to foreign navies.

Hamilton (WHEC-715)

(Not to be confused with the current Legend-class cutter, Hamilton (WMSL-573))

USCGC Hamilton was homeported in Boston, MA, from February 1967 to 1980. During that time, she was used for search-and-rescue, ocean station, and law enforcement duties. On 6 May 1968, Hamilton medevaced a seaman from FV Little Growler. Then, on 5 July 1968, she assisted the British MV Tactician, which was in distress. From 1 November 1969 to 25 May 1970, she was assigned to duty in Vietnam with Coast Guard Squadron Three, along with the cutters Dallas (WHEC-716), Mellon (WHEC-717), Chase (WHEC-718), and Ponchartrain (WHEC-70). This included participating in the U.S. Navy’s Operation Market Time to interdict enemy supply vessels, as well as providing coastal surveillance and naval gunfire support. During her time in Vietnam, Hamilton interdicted enemy weapons shipments, fired more than 4,600 rounds for gunfire support missions, and the crew participated in medical civilian assistance programs (MEDCAPs) that provided temporary medical dispensaries, civic action, and charitable projects to civilians. Following her service in Vietnam, Hamilton returned to her home port of Boston and continued duties on various Ocean Stations. From 1980 to 1981, she was stationed in New York, NY, and used for search-and-rescue and law enforcement duties. She returned to Boston the following year. Hamilton later took part in Operation Buccaneer to surveil and interdict drug shipments in the Windward Passage. On 6 October 1981, she seized 18.5 tons of marijuana from Dona Victoria. Eight days later, she seized 7.5 tons of marijuana from Danny. On 22 July 1982, she stopped Wanda, which was found to be carrying 2.5 tons of marijuana. Later that year, on 18 November 1982, she seized 7.5 tons of marijuana from Ramses II. On 26 March 1983, Hamilton was forced to disable Anna I with 18 rounds of 20mm gunfire after she refused to stop. Anna I was found to be carrying contraband. On 9 December 1983, she stopped Vanessa and seized one pound of marijuana. On 1 February 1984, Hamilton seized 12 tons of marijuana from the FV Rama Cay, 300 miles north of the Caicos Islands in the Caribbean Sea. On 24 May 1984, she seized 9 tons of marijuana from Janeth near Crooked Island. On 27 November 1984, Hamilton intercepted the FV Princess 65 miles north of Punta de la Cruz, Colombia. However, the crew of Princess scuttled the boat to prevent her from being boarded. Operation Buccaneer ended that year. Hamilton underwent her FRAM upgrades at Bath Iron Works from October 1985 to December 1988. In 1991, Hamilton‘s homeport was changed to San Pedro, CA.20

From 1993 to 1994, Hamilton took part in Operations Able Manner and Able Vigil. During Able Manner (15 January 1993 to 26 November 1994), Hamilton was the on-scene commander in charge of 17 cutters, 9 aircraft, and 5 U.S. Navy vessels that were operating off the Haitian coastline. Together, they intercepted 25,177 migrants fleeing Haiti (as many as 3,247 in a single day). In total, Operation Able Manner consisted of more than 6,000 cutter days and 14,000 flight hours. Operation Able Vigil lasted from 19 August to 23 September 1994 and involved 29 cutters (including the Hamilton), 6 aircraft, and 9 U.S. Navy vessels that operated in the Straits of Florida. These assets ultimately intercepted 30,224 Cuban migrants (as many as 3,253 in a single day). Hamilton also rescued 135 Haitians after their sailboat capsized and sank. For her rescue efforts, she was awarded the Coast Guard Meritorious Unit Commendation.21

In 1996, Hamilton was assigned as the command-and-control platform for Operation Frontier Shield. She deployed to Panama in a multi-agency effort to curb the narcotics entering the U.S. via the Panama Canal and the Caribbean Sea. In total, she seized 14 vessels carrying more than 115 tons of contraband worth $200 million. In 1999, Hamilton seized more than 5,952 pounds of cocaine in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Also, that year, her homeport was changed to San Diego, CA. In March 2007, Hamilton and Sherman stopped the Panamanian-flagged FV Gatun in international waters and seized 20 metric tons of cocaine worth an estimated $600 million. It was one of the largest drug busts in Coast Guard history. In 2010, during her final year of service in the Coast Guard, Hamilton sailed for 205 days, covering over 50,000 nautical miles, and supported Haitian earthquake relief efforts, counter-narcotic operations, and conducted a winter patrol in the Bering Sea.22 She was decommissioned from the U.S. Coast Guard on 28 March 2011. Following her Coast Guard service, Hamilton was transferred to the Philippine Navy on 13 May 2011 and recommissioned as BPR Gregorio del Pilar (PF-15).

Dallas (WHEC-716)

USCGC Dallas was stationed in New York, NY, from 26 October 1967 to 1996 and used for search-and-rescue, law enforcement, and ocean station duties. On 19 September 1968, she assisted the Dutch tanker Johannes Frans, which was disabled 250 miles northeast of Bermuda. Dallas provided dewatering pumps and other materials to keep the ship afloat. After three days, two commercial tugs arrived and towed the stricken vessel to Bermuda.23

From 3 November 1969 to 19 June 1970, Dallas was assigned to Coast Guard Squadron Three off Vietnam.24 During her time in Vietnam, Dallas conducted 161 naval gunfire support missions, fired 7,665 rounds of ammunition, destroyed 58 sampans, and destroyed or damaged 29 enemy supply routes, base camps, and rest areas. One of her notable actions occurred in April of 1970 when Dallas supported a South Vietnamese Army sweep. She provided gunfire support for 300 South Vietnamese troops who were pinned down and in danger of being overrun by enemy forces. After firing nearly every projectile in the magazine, Dallas stopped the enemy attack. In addition to gunfire support missions, Dallas’s crew rendered medical aid to over 1,500 South Vietnamese citizens; built a dispensary, a playground, and school benches for 300 children; and painted a school building. For her service in Vietnam, Dallas earned the Navy’s Meritorious Unit Commendation.25 Dallas served on various ocean stations upon returning from Vietnam.

In 1973, Dallas participated in the search for survivors of the cargo ship Norse Variant, which broke apart 250 miles off the New Jersey coast. Only one survivor was saved. In 1978, Dallas took part in the search for the missing FV Capt. Cosmo. During the search, she encountered heavy seas with waves as high as the bridge wings. Unfortunately, neither Capt. Cosmo or any of her survivors were ever found. In June 1979, Dallas seized the FV Foxy Lady, which was found to be carrying 15 tons of marijuana. The vessel was interned in San Juan, Puerto Rico.26

From May to June 1980, Dallas served as the on-scene commander for patrols during the Mariel boatlift, a refugee exodus that involved more than 100,000 people fleeing Mariel, Cuba, and Haiti in dangerously unseaworthy craft. This would turn out to be the largest humanitarian response in Coast Guard history up to that point. At times, Dallas had up to 500 refugees on board and provided aid to over 300 boats. During this six-week effort, Dallas coordinated the response of a dozen larger cutters and numerous smaller cutters and patrol boats, as well as Navy and Marine Corps assets.27

Throughout the rest of the 1980s, Dallas continued to interdict drug shipments in the Caribbean. On 6 June 1982, Dallas seized 5.5 tons of marijuana from Yvette. On 24 October 1982, she seized Libra, which was found to be carrying 3.5 tons of marijuana. From 7 to 8 April 1983, she assisted the grounded sailboat Leo and towed the MV Grace a Dieu to Tortuga Island after it had become disabled in the Windward Passage. On 25 October 1983, she seized Saint Nicholas, which was carrying 13 tons of marijuana. On 3 November 1983, she stopped Narwal, which was carrying 15 tons of marijuana. Three days later, on 6 November, Dallas stopped Miss Debbie, which was carrying 11.5 tons of marijuana. On 13 November, she boarded Nistanova and seized 4 tons of marijuana. On 16 November, Dallas seized 5 tons of marijuana from W and V. On 23 November, she seized 2.5 tons of marijuana from El Vira III. For her fall 1983 patrol in the Caribbean, Dallas received the Coast Guard Unit Commendation. In all, she interdicted 90 Haitian immigrants, made seven drug seizures, 51 arrests, and confiscated 50 tons of marijuana. The following year, on 17 June 1984, Dallas seized the MV Stecarika and the sailboat Esperance 150 miles southwest of Puerto Rico after finding contraband in concealed compartments. On 23 February 1985, she seized Star Trek, which was carrying 15 tons of marijuana.28 Apart from drug seizures, Dallas served as the on-scene coordinator for the recovery of debris from the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger off Cape Canaveral, FL, from 28 January to 7 February 1986.29 For her role in the response, which was the largest search and rescue operation in Coast Guard history at the time, Dallas received the Coast Guard Meritorious Unit Commendation.30

Dallas underwent her FRAM upgrades at Bath Iron Works in Bath, ME, from November 1986 to December 1989.31 Further upgrades were added between 1991 and 1993. These included improvements to the Shipboard Command and Control Systems (SCCS), mounting the Phalanx CIWS, and installing the INMARSAT global commercial satellite telephone uplink for advanced ship-to-shore telecommunications.32

Following the 1991 coup d’etat in Haiti, Dallas served as the on-scene commander for a flotilla of 27 Coast Guard cutters (the largest ever assembled) during the exodus of Haitians fleeing the country. As the flagship of Task Unit 44.7.4, Dallas served as a model for an operational organization that continues to be used with multi-unit operations in the Coast Guard. The Task Unit ultimately rescued nearly 35,000 migrants and transported them to the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for processing by immigration officials. For its efforts during the crisis, Dallas would receive the Humanitarian Service Medal and the Meritorious Unit Commendation with the operational distinguishing device.33

On 4 July 1992, Dallas served as the command and control platform for Coast Guard assets on the Hudson River during a tall ship parade commemorating the 500th anniversary of the voyage of Christopher Columbus. In 1993, Dallas seized the MV Gladiator, which was smuggling over 5,500 pounds of cocaine. That same year, she assisted the capsized Haitian ferry, Neptune, which had over 800 passengers aboard. She also medevaced an ill crewmember from the Ukrainian cruise ship Karelya in the first use of a ship-deployed Coast Guard HH-60 Jayhawk helicopter. In response to large numbers of people fleeing Haiti in 1993, 22 Coast Guard and Navy ships, and 22 aircraft were deployed to participate in Operation Able Manner to deter migrants attempting the dangerous voyage. Dallas served as the flagship of Task Unit 44.7.4 on three separate patrols from 1993 to 1994 (February to April, July to September, and December to January 1994). For her efforts, Dallas earned a Coast Guard Unit Commendation.34

While returning from one of her deployments to Operation Able Manner in 1993, Dallas stopped the MV Mermaid No. 1 and discovered it to be carrying 237 Chinese migrants. From April to May 1994, during the Joint Service Exercise Able Provider, Dallas served as the tactical control unit for three 110-foot Coast Guard patrol boats and had the role of the anti-surface warfare commander for the task force that was conducting an amphibious assault exercise off the beaches near Camp Lejeune, NC. Following that exercise, Dallas represented the U.S. Coast Guard at the 50th anniversary of the D-Day invasion at Normandy. During that time, she participated in the invasion re-enactment fleet and made port calls in Ireland, the UK, and France. After the D-Day anniversary, Dallas made goodwill visits to Morocco and the Cape Verde Islands. Returning from Europe to the Caribbean, Dallas participated in Operation Able Vigil as the flagship for a 27-cutter flotilla that was responding to a mass migration from Cuba. Dallas later coordinated the repatriation of Haitian migrants from Guantanamo Bay to Haiti. She received the Coast Guard Unit Commendation for this operation.35

During the summer of 1995, Dallas joined USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) Battle Group as part of the Sixth Fleet to support Operations Deny Flight and Sharp Guard that was blockading materials to the former Yugoslavia. This was the first time a Coast Guard cutter had operated with the Sixth Fleet. During this time, she conducted training and professional exchanges with countries in the Mediterranean, Adriatic, and Black Seas (Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, Tunisia, Albania, and Italy). Dallas also became the first Coast Guard ship to operate in the Black Sea and received the Armed Forces Medal for her support.36

During the last few months of 1995, Dallas went in for an extensive dry dock period. The overhaul included removing the sonar dome, installing a new water evaporator, and overhauling the ship’s antennas, transducers, steering gear, and bow prop. Her AN/SPS-40 radar was also upgraded, and two fuel tanks were converted to carry JP-5 aviation fuel for helicopters and the ship’s gas turbines. Finally, the ship was sandblasted and re-painted. The total cost of the dry docking was $2.2 million.37

Dallas would be back in the Caribbean in 1996 doing counter-drug operations. On 11 August 1996, Dallas seized the Colombian-registered MV Colopan, which was found to be carrying 3,850 pounds of cocaine. On 21 August, she stopped the Haitian MV Express that was smuggling 767 pounds of cocaine. During Operation Monitor II in the late summer of 1996, Dallas served as the flagship for a task unit of three 110-foot cutters monitoring groups of Cuban-American vessels protesting the sinking of a Cuban tugboat. The operation successfully kept the boats out of Cuban waters, and the Cuban Navy did not interfere. In 1997 and 1998, Dallas took part in Operations Frontier Shield and Frontier Lance. These were counter-drug operations in the Caribbean using enhanced surface and airborne radar, infrared surveillance, covert tracking, and rapid response assets. Frontier Lance was the successor to Frontier Shield. It utilized C-130 aircraft, shipboard HH-65 Dolphin helicopters, and rigid-hulled inflatable boats. Additionally, Operation Frontier Lance saw the first use of MH-90 Enforcer helicopters that would eventually lead to the formation of the Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron (HITRON) and their Airborne Use of Force (AUF) tactics. The interagency cooperation and intelligence provided during these operations ultimately proved highly effective.38

Following the terrorist attack on 9/11, Dallas was stationed off the southeastern U.S. as part of Operation Noble Eagle. During that time, she monitored and boarded vessels entering U.S. waterways. This marked a shift in Coast Guard operations from drug and migrant interdiction to homeland security missions. The following summer of 2002, Dallas deployed with the cutter Gallatin (WHEC-721) to take part in Operation New Frontier. The two cutters supported HITRON helicopters, stopping high-speed (“go fast”) drug boats carrying contraband to their destinations. In 2003, Dallas deployed to the Mediterranean and again joined the Sixth Fleet in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom. As part of Patrol Forces Mediterranean (PATFORMED), which included four 110-foot patrol boats, Dallas escorted Coalition vessels transiting the Strait of Gibraltar and boarded vessels exiting the Suez Canal in search of any Iraqi leaders who might be trying to escape via the Mediterranean Sea. Dallas made several port calls in the region before returning to the United States with the other patrol boats.39

In the summer of 1999, Dallas was again assigned to the Sixth Fleet to support Operation Allied Force during the Kosovo War. Although the conflict was resolved as Dallas was in transit, she remained in the region to train Ukrainian and Georgian naval personnel, as well as the Turkish Coast Guard and the armed forces of Malta.40

In September 2006, Dallas intercepted the 60-foot fishing vessel Desperado, which was carrying 78 illegal Cuban migrants. A law enforcement team arrested the crew of four smugglers and provided aid to the people on board. Dallas later took custody of eight Cuban migrants who had been rescued by USNS Cobb. All the detainees and migrants were later transferred to another cutter for processing. On 17 October 2006, Dallas recovered four bales of cocaine weighing 380 pounds from a foiled airdrop to a smuggling boat. In the spring of 2008, Dallas deployed to West Africa to participate in the Africa Partnership Station (APS), which sought to strengthen international relationships. During that time, she hosted law enforcement personnel from the Cape Verde Islands and became the first U.S. vessel to assist a foreign country with law enforcement in its own waters. Later that year, in the summer, Dallas joined the Sixth Fleet and participated in Operation Assured Delivery to provide humanitarian aid to the Republic of Georgia, which was impacted by the Russo-Georgian War. In January 2010, Dallas deployed to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, following the 7.0 magnitude earthquake that had struck the country and helped to coordinate the air and maritime assets responding to the disaster. Also, that year, Dallas seized several smuggling boats and a self-propelled semi-submersible. In total, Dallas confiscated 5.5 metric tons of cocaine in 2010. During her final Caribbean patrol in 2012, Dallas seized 5,000 pounds of cocaine and 1,000 pounds of marijuana.41

Dallas was decommissioned from the U.S. Coast Guard on 30 March 2012 and transferred to the Philippine Navy, where she was recommissioned as the frigate BRP Ramon Alcaraz (PF-16).

Mellon (WHEC-717)

USCGC Mellon was homeported in Honolulu, HI, from 22 December 1967 to 1980 and used for search-and-rescue, ocean station, and law enforcement duties.42 She was one of the newer ships of her class to have a joystick helm, whereas the previous High Endurance Cutters were equipped with standard ship wheels as helms.43 Whether or not the earlier-commissioned cutters of the class, Hamilton and Dallas, also had joystick helms is unknown. Mellon’s first Commanding Officer, Captain Robert P. Cunningham, was also the first Coast Guard aviator to command a 378-foot cutter.44 Shortly after her commissioning and arrival at Honolulu, Mellon took part in a naval review in San Diego, CA. A state-of-the-art design, at the time, she demonstrated her impressive maneuverability and speed when she reached speeds greater than 20 knots in less than two ship lengths from a standing stop. Newspapers reported that she could attain 20 knots in less than 20 seconds and go from full ahead to full astern in less than 60 seconds. Additionally, with her bow propulsion unit, she was also able to maneuver into a narrow berth without the assistance of tugs.45

From 31 March to 2 July 1970, Mellon was in Vietnam serving with Coast Guard Squadron Three. During that time, she conducted naval gunfire support missions, rescue operations, and interdicted enemy weapons shipments along the coastline of Vietnam. Along with other Coast Guard cutter crews, Mellon‘s crew also participated in medical civic action programs and trained Vietnamese military personnel. Upon returning from Vietnam, Mellon served on Ocean Station duty throughout the Pacific. In April 1972, she seized the Japanese fishing vessels Kohoyo Maru 31 and Ryoyo Maru for fisheries violations. On 11 February 1974, she medevaced a crewman from the Norwegian MV Norbeth in the mid-Pacific.46 Also that month, Mellon assisted in the rescue of crewmembers from the Italian supertanker Giovanna Lolli-ghetti that had sunk 230 miles southeast of Hawaii following an explosion. After receiving the distress call around midnight, Mellon arrived on the scene around 1115 the following morning. The Norwegian vessel Tamerlane was in the process of rescuing survivors who were then transferred to Mellon for medical care. Also during that rescue, and despite Cold War era tensions between the countries, the Russian vessel Novikov Privoy arrived with doctors to render further assistance. Mellon took all but 7 of the survivors back to Honolulu. In February 1975, Mellon assisted the freighter London Pioneer that had become disabled by a flash fire in her engine room 900 miles northeast of Honolulu. Later during that same patrol, Mellon assisted the Liberian bulk carrier Rose S., which was taking on water in heavy seas at 300 tons per day. Rendezvousing with the ship 300 miles northwest of Honolulu, Mellon helped pump 250 tons of seawater overboard and towed the vessel back to Honolulu. In August of that year, Mellon responded to Ryukyo Maru, which was leaking fuel oil into the Bering Sea near St. Paul Island. She arrived and anchored nearby, then supported efforts to contain the spill of more than 300,000 gallons of oil. For her operations between 28 June 1975 and 2 February 1976, Mellon was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation due to her efforts at tracking and reporting vessels that were illegally discharging oil into the sea.47

Mellon‘s operations shifted to the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea when the Ocean Station program ended, and the Magnuson Fishery Conservation and Management Act was passed in 1976. On 11 May 1976, the sloop Sorcery was dismasted by a large wave while on a trans-Pacific voyage from Tokyo to San Francisco with 11 crewmembers on board. With her navigation equipment destroyed, a distress call was made using a HAM radio on board. Mellon was near Kodiak, AK, and responded, but didn’t know the sloop’s last known position. Two unknown HAM operators were able to relay messages between Mellon and Sorcery, and Mellon was eventually able to evacuate the crew. Several of these crewmembers were then evacuated by helicopter for additional treatment ashore. Sorcery was later towed into port.48

On 18 November 1976, Mellon responded to a distress call from the MV Carnelian I. which was 100 miles north of Oahu and in danger of foundering. Coast Guard aircraft attempted to drop survival gear on the vessel, but weather conditions, including high winds, low visibility, and rough seas, impaired the rescue. Carnelian I. sank, but Mellon arrived on-scene and recovered 16 of the 33 crewmembers who were found clinging to floating debris. On 6 March 1977, Mellon responded to a volcanic eruption on Seguam Island in the Aleutians. Also, that year, the first women were assigned to the cutter.49 On 9 December 1979, Mellon seized the FV Ryuho Maru 38 for fishing violations.50

On 30 September, the 427-foot luxury liner Prinsendam departed from Vancouver, British Columbia, on a 31-day cruise through the inside passage of southeast Alaska and across the Pacific with stops in Ketchikan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore. She had a total of 519 persons aboard, including 164 Indonesian crew members, 26 Dutch officers, and 329 passengers, most of whom were elderly. Around midnight on 4 October 1980, a fire broke out in the engine room of Prinsendam, which was 120 miles south of Yakutat, AK.51 With the fire raging out of control, the vessel’s captain sent out a distress call. The Rescue Coordination Center in Juneau organized the response, which included a C-130 and an HH-3 helicopter. Mellon was on patrol near Vancouver, BC, and began heading toward the scene, 550 nautical miles away. As other cutters were diverted to assist, the 1000-foot supertanker, Williamsburgh, was also diverted to render assistance. At approximately 0630, Prinsendam began evacuating, with 15 passengers and 25 crewmembers remaining on board. Williamsburgh arrived at 0745, and the on-scene helicopter began transferring survivors from the lifeboats onto the deck of the tanker. Around mid-afternoon, the cutter Boutwell arrived and took on survivors in critical condition for transfer to Sitka, AK. Mellon arrived around 1830 and dispatched a medical team to Williamsburgh to render medical assistance. By 2100, 20 passengers and 2 Air Force aviator technicians were still reported missing in one of the lifeboats. Coast Guard Command in Juneau directed Boutwell and a C-130 to search for the missing lifeboat, which was located around 0100 after a flare from the boat was spotted. Amazingly, at the end of the rescue, all of Prinsendam‘s passengers and crew were alive and accounted for with no serious injuries.52

On 26 October 1980, Mellon seized Ryuho Maru 38 (again) for fishing violations near Alaska. Mellon‘s homeport was changed to Seattle, WA, from 1981 to 1990. During her first Alaskan patrol after transferring to Seattle, Mellon participated in the rescue of four crewmen from a C-130 that crashed on Attu in 1982. In August 1982, she assisted the MV Regina Maris off Hawaii. On 14 February 1984, she assisted in the rescue of survivors from Kyowa Maru 170 miles off St. George Island, AK. Mellon underwent her FRAM upgrades from October 1985 to March 1989 at Todd Shipyard in Seattle, WA.53 For her successful execution of several military readiness missions from 6 February 1989 to 27 February 1990, Mellon received the Coast Guard Unit Commendation Medal. This included her successful test firing of a Harpoon antiship missile on 16 January 1990. While five Hamilton-class cutters received Harpoon missiles, Mellon was the only one to perform a test firing. Budget constraints eventually saw the missiles removed from the cutters.54

Mellon made a diplomatic visit to Vladivostok, Russia, in 1991 to join the 73rd anniversary of the Russian Maritime Border Guard. In 1992, Mellon represented the Coast Guard in Portland, OR, for the start of their “Just Say No to Drugs” campaign. She made several subsequent visits to the city. Also in 1992, Mellon received the Admiral John B. Hayes Award from the Coast Guard Foundation for its achievements as a Pacific Area unit. She would also conduct professional exchanges with maritime agencies in Costa Rica and Panama in 1993. In the spring of 1994, Mellon was engaged in two pursuits of Russian fishing vessels suspected of poaching in the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. One interesting event occurred during a patrol in 1998. Mellon steamed at high speed for several hundred miles to assist an injured sailor on a sailboat. Embarking a U.S. Air Force pararescue team, Mellon launched her embarked helicopter with the PJs aboard who located the vessel. Dropping the PJs into the water, they boarded the boat and began treating the patient. Eventually, the sailor was transferred to Mellon via helicopter and then flown ashore for further treatment.55

Mellon spent the remainder of her career in the Coast Guard patrolling the Bering Sea and the eastern Pacific around Mexico and Central America. In the Bering Sea, she typically patrolled the Maritime Boundary Line between the U.S. and Russia. Frequently coming into contact with Russian, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese fishing vessels pursuing their pollock catch across the line, Mellon would be assisted by air assets in conducting her law enforcement operations. Mellon also conducted fisheries enforcement along the Alaska Peninsula. During patrols to Central America, Mellon acted as part of the national “Steel Web” strategy to deny narcotics smugglers access to the U.S. via maritime routes. Additionally, Mellon would enforce immigration laws and stop vessels attempting to smuggle people into the U.S.56

Mellon was decommissioned from the U.S. Coast Guard on 20 August 2020. She was originally slated for transfer to Bahrain but is now awaiting transfer to the Vietnam Coast Guard.

Chase (WHEC-718)

From 1 March 1968 to 1990, USCGC Chase was stationed in Boston, MA, and used for law enforcement, search-and-rescue, and ocean station duties. From 6 December 1969 to 28 May 1970, Chase, along with the cutters Hamilton (WHEC-715), Dallas (WHEC-716), Mellon (WHEC-717), and Pontchartrain (WHEC-90), was assigned to Coast Guard Squadron Three in Vietnam. As part of the Navy’s Operation Market Time, the squadron conducted coastal surveillance and at least 12 naval gunfire support missions for troops ashore. She also conducted underway replenishment with Navy replenishment vessels and resupplied smaller Coast Guard vessels in the theater. Chase‘s crew also participated in medical civilian assistance programs (MEDCAPs). For her service in Vietnam, Chase received the Navy Meritorious Unit Commendation and the Vietnam Service Medal. She continued to serve on ocean stations throughout the 1970s. In 1973, Chase participated in Operation Seaconex with seven destroyers and an amphibious assault ship to test their abilities to defend a convoy against air, surface, and subsurface threats. In 1976, while on a cruise with Coast Guard cadets, Chase joined Operation Fluid Drive and, along with the aircraft carrier USS America and the landing ship USS Spiegel Grove, evacuated U.S. nationals from Beirut, Lebanon, after the assassination of two U.S. officials.57

In August 1980, Chase assisted the U.S. containership American Apollo 6, which was 6 miles off the southwest coast of Haiti. In October 1981, she intercepted a sinking 30-foot sailboat 120 miles northwest of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, carrying 57 illegal Haitian refugees. The refugees were later repatriated to Haiti. On 12 November 1981, Chase seized 5 tons of marijuana from Fao. On 29 November 1981, she seized Cary, which was carrying 1.5 tons of marijuana. On 5 December 1981, she seized Captain Romie carrying 1 pound of marijuana. On 11 July 1982, Chase turned back an 18-foot sailboat with 8 Haitians aboard off southeast Cuba. On 7 January 1983, she seized the MV Juan Robinson 270 miles off Bermuda, which was carrying 17 tons of marijuana. In 1982 and 1983, Chase participated in exercises Safe Pass, United Effort, and Ocean Safari with U.S. Navy and NATO warships. These exercises tested her ability to operate with foreign naval forces under wartime conditions. Chase also participated in Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. invasion of Grenada, from October 1983 to July 1984. For this service, Chase received the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal. In May 1985, a fire broke out in the engine room while Chase was cruising off Cape Cod after returning from the Caribbean. The fire disabled the propulsion of the cutter and killed one crewman, MK3 Nicholas V. Barei. The cutter Chilula (WMEC 153) later arrived and towed Chase into Boston. In September 1987, she intercepted the fishing vessel Bethsioa, which was illegally carrying 72 Haitians who were then repatriated. On 24 September 1987, Chase seized 5 tons of marijuana from FL-6907-FR. On 10 October 1987, she seized the vessel New Year, which was carrying 3 tons of marijuana. In total, from 1981 through 1987, Chase interdicted ten smuggling vessels and seized over 66 tons of marijuana. Between January 1985 and March 1988, Chase repatriated more than 338 migrants during the Haitian Migration Interdiction Operations (HMIO).58

Chase underwent her FRAM upgrades at Bath Iron Works in Bath, ME, from July 1989 to 1990.59 She returned to service on 22 March 1991. Later in July, when returning from refresher training, Chase struck a whale that damaged a screw and left her disabled 70 miles off Cape Cod. The cutter Harriet Lane (WMEC 903) towed Chase into port for repairs.60

All but two of the Hamilton-class cutters were transferred to Pacific ports following the termination of the Ocean Stations in the Atlantic. The high-endurance cutters were deemed more suitable for the longer distances of the Pacific and for policing the fishing grounds in rough weather. Chase arrived in San Pedro, CA, on 15 November 1991. On 22 December 1992, Chase represented the United States in Vladivostok, Russia, as the U.S. Consulate was reestablished there. In 1994, Chase led U.S. forces into Port-au-Prince, Haiti, to establish the first Harbor Defense Command in foreign waters. She later participated in Operations Able Manner and Able Vigil, during which she interdicted 130 Cuban refugees. In 1995, Chase stopped the motor vessel Xin Ji Li Hou off Baja California, Mexico, and interdicted 150 Chinese migrants.61

From April to June 1997, Chase was the first Coast Guard cutter to participate in Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training (CARAT) in Southeast Asia. Chase trained with the Royal Thai Navy and visited various ports in Thailand. She later received the Coast Guard Meritorious Unit Commendation for stopping the high seas drift net vessel, Cao Yu. In 1998, Chase joined USS Russell (DDG-59), USS Crommelin (FFG-37), and USS O’Brien (DD-975) for Military Interdiction Operations (MIO) in the Persian Gulf. Chase assisted in diverting four vessels that were violating UN sanctions against Iraq. She also reported a spill of 1,527,740 gallons of fuel oil and took part in 85 gunnery exercises. In 1999, Chase seized seven metric tons of cocaine from a vessel. At the time, this was the second-largest drug bust in Coast Guard history. In August 1999, Chase was transferred to San Diego, CA.62

Chase was decommissioned from the U.S. Coast Guard on 29 March 2011 and transferred to the Nigerian Navy, which recommissioned her as the frigate NNS Thunder (F90).

Boutwell (WHEC-719)

USCGC Boutwell was homeported in Boston, MA, from 24 June 1968 to 197,3 where she was used for ocean station, search-and-rescue, and law enforcement duties. On 11 October 1969, she medevaced crewmen from the Liberian MV Saint Nicholas in the mid-Atlantic. On 13 February 1970, she rescued two from a drifting barge off Jamaica.63 In February 1972, while on ocean station duty, Boutwell was dispatched to surveil a disabled Soviet submarine 600 miles northeast of St. John’s, Newfoundland, after it had been spotted by a U.S. Navy P-3 Orion aircraft. Locating the submarine, Boutwell offered assistance but received no reply. Trailing the sub for nine days, from 26 February to 5 March, Boutwell negotiated 60-foot seas and 80-mile-per-hour winds, remaining with the disabled sub. On 5 March, Boutwell was relieved by the cutter Gallatin, which remained on-scene until 21 March when Soviet vessels arrived and towed the sub to a port.64

After five years in the Atlantic, Boutwell was transferred to a new homeport in Seattle, WA. While en route, Boutwell assisted the FV Juliette that was taking on water 40 miles northwest of Depoe Bay, OR. Boutwell successfully stopped the flooding and escorted the vessel to safety.65 On 17 October 1973, while patrolling near Alaska, Boutwell assisted the FV Sundance that was taking on water north of Kodiak. After a repair party successfully controlled the flooding, she escorted the vessel to Kodiak. Boutwell also participated in the unsuccessful search for the missing crab boat Dauntless.66

On 19 December, Boutwell got underway from Seattle in response to a distress call from SS Oriental Monarch that was sinking in heavy seas 500 miles off Victoria, British Columbia. Despite sprinting to her location, Oriental Monarch sank, and Boutwell commenced recovery operations. She was able to locate six bodies.67

After a period of refresher training in San Diego, Boutwell joined the U.S. Third Fleet and several Canadian vessels for Exercise Bead Coral. This involved 20 ships and 120 aircraft, emphasizing anti-submarine and air defense tactics. Following the exercise, Boutwell was on ocean station duty, and after being relieved by Mellon, a fuel line broke and caused a fire in her engine room, which damaged one diesel and one gas turbine engine. With the fire subdued, Boutwell made her way back to Seattle for repairs.68

On 16 January 1976, Boutwell responded to the 476-foot Panamanian freighter, Caspian Career, that was about 1,100 miles west of San Francisco. She had suffered cracks in her hull plating and was flooding in her hold. Although the crew tried to pump out the water, the pumps became clogged with the cargo of potash, and the crew resorted to manually bailing out the water with buckets. As the flooding increased to 20 feet, the bulkheads of the adjacent holds began to buckle under pressure. After locating the vessel, Boutwell sent over dewatering pumps, and the crew managed to pump out the water to about 10 feet in the hold. Coast Guard cutter Resolute (WMEC-620) eventually arrived to escort Caspain Career to San Francisco, which she reached on 23 January. Later that spring, during an Alaska patrol, on 24 April, Boutwell towed the NOAA vessel Surveyor to Kodiak, AK, after she had suffered a casualty in her reduction gear. Following this patrol, Boutwell participated in Operation READIEX 4-76 off the coast of southern California from 21 to 30 June. This involved 14 ships and was designed to test the readiness of the U.S. Third Fleet. The exercise stressed anti-submarine and surface warfare tactics.69 While on her way home from another Alaska patrol on 11 October, Boutwell diverted to assist the FV Blue Swan that was taking on water and in danger of sinking off Victoria, British Columbia. Arriving in time, Boutwell assisted in successfully dewatering the vessel before handing her over to the cutter Point Bennett (WPB-82351), who escorted her to safety.70

When the Magnuson–Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act was passed in 1976, the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) was extended from 12 to 200 nautical miles. As a result, Boutwell‘s patrols increased in the Bering Sea. On 15 May 1977, Boutwell medevaced an injured Japanese fisherman from Jikyu Maru. The following month, Boutwell rescued four men from a life raft after their vessel, Ahaliq, had sunk 45 miles north of Port Heiden. Boutwell continued to perform patrols around Alaska and conducted 69 boardings of foreign fishing vessels to ensure compliance with laws.71 Boutwell continued to do Alaska patrols and refresher training throughout the remainder of the 1970s. In the summer of 1979, Boutwell participated in Operation ARCTIC WEST and became the second Hamilton-class cutter to cross the Arctic Circle. In addition, she conducted 15 law enforcement boardings and two search-and-rescue cases before returning home on 19 August.72

On 4 October 1980 at 0140, Boutwell received urgent tasking to get underway from Juneau, AK, when a fire broke out in Prinsendam‘s engine room. In addition to Boutwell, other assets responding to the distress call were Coast Guard cutters Woodrush (WLB-407) and Mellon, along with the tanker Williamsburgh. Air assets included four U.S. Coast Guard HH-3 Pelican helicopters, two HC-130 Hercules aircraft, one U.S. Air Force HH-3 helicopter, and one HC-130 Hercules refueler. The Canadian Armed Forces also contributed two CH-46 helicopters and three fixed-wing aircraft. With the evacuation underway, Prinsendam had six lifeboats, one covered motor launch, and four life rafts. With seas at 5 – 10 feet and winds of 10 – 15 knots, 50 crew remained aboard to fight the fire.73

Unfortunately, the weather continued to deteriorate with helicopters continually lifting survivors off Prinsendam and depositing them onto the deck of Williamsburgh. Boutwell arrived on-scene at 1345 as the seas grew to 20 – 35 feet with winds of over 25 knots. Boutwell recovered the remaining survivors as Williamsburgh headed for Yakutat, AK. By 1845, all 519 survivors were accounted for. However, upon doing another head count, two Canadian pararescuemen remained unaccounted for, having last been seen in a lifeboat with 18 survivors. Boutwell and Woodrush commenced a search for the lifeboat at 0015 on 5 October, which was located about 45 minutes later. Boutwell arrived in Sitka later that day with 83 survivors. Williamsburgh later arrived in Valdez with over 380 survivors. Prinsendam later sank on 10 October due to damage resulting in increased flooding.74

On 20 October, Boutwell responded to the oil platform Dan Prince, which had suffered structural damage in heavy weather and was adrift after its tow cable had broken. With Dan Prince’s ballast tanks damaged and in danger of sinking, Boutwell evacuated the 18 crew aboard, and the platform capsized and sank at 0525 on 22 October. From 8 – 15 December, Boutwell took part in Operation READIEX 1-81 with the U.S. Navy. Shortly after that, she participated in the naval exercise KERNEL USHER 1-81, which was an amphibious exercise involving 1,500 Marines, five U.S. Navy amphibious assault ships, one Forrest Sherman-class destroyer, and one attack submarine. In addition to focusing on anti-air and anti-missile defense, the exercise included special operations with Navy SEALs.75

On 9 March 1981, Boutwell, with a U.S. Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal team, responded to the grounded 291-foot Korean freighter Daerim that had caught fire on 27 February and had been abandoned after a failed tow by a Soviet salvage ship. Fearing that Daerim‘s 110,000 gallons of diesel fuel posed an environmental hazard, the Navy EOD team detonated explosives aboard in hopes of venting and burning off the fuel. Later, Boutwell raked the ship with machine gun fire, which successfully punctured and vented the remaining fuel tanks. On 28 August, while en route home, Boutwell was diverted to assist the U.S. Third Fleet in monitoring a Soviet warship flotilla in the Gulf of Alaska. The Soviet ships included a Kara-class missile cruiser, two Kirva-class guided-missile frigates, a replenishment vessel, and a suspected submarine. All were headed south along the Pacific coast. It was believed they were conducting a display of force following the shoot-down of two Libyan fighters by American aircraft in the Mediterranean. Boutwell assisted in tracking the Soviet vessels until relieved by Canadian forces.76

On 20 June 1982, while on an Alaskan Fisheries Patrol, Boutwell sighted the 39-foot sailboat, Orca, approximately 700 miles south of the Aleutians. Upon boarding the vessel, the team discovered numerous foil and plastic-wrapped packages that tested positive for marijuana. In total, 580 packages, each weighing about five pounds, were recovered for a total of over 3,100 pounds of Southeast Asian marijuana with an estimated street value of $3 million. With the crew interred, Boutwell took Orca under tow and set a course for Dutch Harbor, having just conducted the first marijuana bust in Alaskan waters.77

As Boutwell transited back to Alaska on 22 June, two of her crewmembers, Fireman D.B. and Seaman Apprentice M.G. (names redacted), were implicated in an attempt to steal the marijuana on board Orca. They had deliberately sabotaged certain pieces of equipment aboard the cutter in an attempt to disable its engines. This included severing a fuel line, damaging some electrical connectors to the emergency gas turbine generator, draining the lubricating oil from one of the primary generators, and shoving a fire hose into a fuel tank. Their plan was to disable Boutwell, cut the towline on Orca, don dry suits, and float to the sailboat to commandeer it and steal the contraband on board.78

Later on the 29th, another crew member, Seaman J.H., attempted to steal the marijuana aboard Orca. This crewman donned a wetsuit and lifejacket and tried to float down the towline, but became entangled and drowned. One watchstander on deck thought they heard a shout for help, so Boutwell stopped, and a head count was taken. Another crew member, Seaman P.C., conspiring with Seaman J.H., reported them as sleeping below decks, so all crew were reported accounted for. When Seaman J.H. was reported missing again, another search was conducted, and Seaman J.H.’s body was found seven hours later. It was later discovered that Seaman P.C. threatened Seaman D.J., who was watching the towline, to report that nothing was amiss. Seaman D.J. failed on three occasions to report seeing Seaman J.H. go overboard. In the end, all the involved parties were later convicted in a court-martial. Boutwell arrived in Kodiak on 2 July to turn over the seized drugs to the Drug Enforcement Agency and the Orca to U.S. Customs. Boutwell then returned to Seattle on 8 July. During the subsequent trial, it was found that Orca‘s real name was Golden Egg. She had departed Singapore on 30 April 1982, made a stop in the Philippines, and a suspected stop in Thailand to load the drugs before setting out for San Francisco. The crew was convicted of drug smuggling and sentenced to upwards of eight years in prison.79

On 12 March 1983, Boutwell was diverted to search for the FV Sea Hawk that had suffered a rudder casualty and capsized 80 miles southwest of Dutch Harbor. Only five of the six crewmembers managed to get survival suits on, and they held on to whatever flotsam they could find to stay afloat. Luckily, Boutwell located and rescued the five survivors after they had spent more than an hour in 33-degree water. The body of the sixth crewmember was never found. On a subsequent patrol on 25 July 1983, Boutwell rescued the crew of the FV Comet that was sinking 14 miles from Dutch Harbor. At the time, Boutwell was 20 miles north of Dutch Harbor and raced to the scene. In what was probably her fastest rescue, Boutwell recovered all four crewmembers a mere five minutes after they had abandoned Comet.80

In September 1986, Boutwell was involved in the unsuccessful search for the FV Normar II that was reported missing on the 11th. The vessel was discovered partially submerged 120 miles northeast of St. Paul Island, but sank before rescuers could arrive.81 In January 1987, Boutwell participated in Exercise Brim Frost 87 to test defenses against sabotage.82 In early February 1987, Boutwell towed the trawler Atlantic Pride some 200 miles to Sitka after she had become disabled when a large wave spilled water down her stack and disabled her power. They both safely arrived in Sitka on 7 February. On 13 February 1987, Boutwell was called to assess whether the FV Fukuyoshi Maru No. 85 could be successfully towed after a propane tank explosion and fire killed a crewmember and forced the 25 remaining crew to abandon her 120 miles northwest of Dutch Harbor. Thankfully, the crew was rescued by her nearby sister ship. Believing that the vessel could only be towed in ideal sea conditions, Boutwell obtained permission from the vessel’s owners and sank her using her 5″ gun.83

After a period of maintenance in Washington, Boutwell continued to conduct patrols in Alaskan waters. By January 1988, there was concern that many foreign fishing vessels were using an area surrounded by the Russian and U.S. Exclusive Economic Zones, known as the “doughnut hole,” as a staging area for incursions into U.S. waters under cover of darkness or severe weather. On 2 February 1988, Boutwell stopped the FV Alaskan Hero, which had earlier illegally transferred 450 metric tons of its catch to a nearby Japanese ship. As it turns out, the Japanese cargo ship Shinwa Maru had been seized in Dutch Harbor on 30 January by the National Marine Fisheries Service since it had no permits to operate in the Gulf of Alaska nor take on cargo from U.S. ships. It could only operate in support of foreign-flagged vessels in the Bering Sea. Boutwell escorted Alaskan Hero into Dutch Harbor, where the crew was taken into custody by U.S. Marshals. Later during the patrol, Boutwell assisted in the medevac of an injured crewman from the Panamanian freighter, Ikan Acapulco. Following her Alaska Patrol, Boutwell participated in the Portland Rose Festival, which included hosting the Junior Miss Rose Festival Princess and her court for a luncheon in the wardroom.84

On 28 June 1988, the officers of Boutwell were briefed in Seattle on a drug shipment in transit from the Far East. Getting underway shortly thereafter, Boutwell received a report from a Coast Guard C-130 that had spotted a flagless oil rig supply ship (Encounter Bay) 500 miles west of the Juan de Fuca Strait, which was making its best speed away from the coast. Boutwell intercepted and determined the vessel to be of possible Panamanian origin. Despite repeated visual and verbal warnings to stop, including several 0.50 caliber machine gun bursts and an inert 5″ shell fired across the bow, Encounter Bay continued to ignore Boutwell’s orders. After receiving permission from the Panamanian Embassy and higher command in the Coast Guard, Boutwell fired 60 rounds from a 0.50 caliber machine gun into Encounter Bay’s engines and disabled her. Upon opening her shipping containers on deck, the boarding team found 72 tons of marijuana, which the ship had loaded while off the coast of Vietnam after departing Singapore on 2 June. As it turns out, some of the intelligence had come from undercover Drug Enforcement Administration agents who were aware of the shipment, but Boutwell‘s commanding officer, Captain Cecil Allison, told reporters the seizure of Encounter Bay was random and not based on prior intelligence. According to Captain Allison, Boutwell had stopped Encounter Bay because it wasn’t flying any flag, the vessel’s name and homeport were obscured, and it looked out of place off the Washington coast. At the time, Boutwell had just conducted the largest maritime drug bust on the West Coast.85

Boutwell underwent her FRAM upgrades at Todd Shipyard in Seattle, WA, from March 1989 to 1990.86 Following her FRAM upgrades, Boutwell’s homeport changed to Alameda, CA. Upon her return to active service, Boutwell participated in an annual sea review in Tokyo with the Japanese Maritime Safety Agency (Japan Coast Guard), which included hosting Japanese dignitaries. Following her visit to Japan, Boutwell patrolled the Bering Sea and rescued the only survivor of the sunken fishing vessel Betty B. on 26 June 1991. She later stopped the fishing vessels Endurance and Hi Seas I. for fishing violations.87

On 25 January 1992, Boutwell stopped Pacific Scout that was illegally trawling near a sea lion rookery north of Unimak Island. Also during that patrol, Boutwell helped to mediate a gear dispute between trawlers and crab boats near the Pribilof Islands. She later evacuated a crewman from Ocean Grace and assisted in fighting a fire aboard the FV Arctic III. Boutwell worked with Alaska Fish and Wildlife Protection officers and National Marine Fisheries Service agents to inspect over 40 vessels suspected of illegal fishing off Alaska, 27 of which were found to have committed violations. Following her patrol, Boutwell headed to San Diego for refresher training. After that, she served as the command center for security forces for the 1992 America’s Cup sailing race and then returned to Alameda. On 10 May 1993, Boutwell intercepted the Honduran-registered fishing trawler Chin Lung Hsiang (Golden Dragon) that was carrying 200 Chinese immigrants off Point Loma. After turning over the illegal immigrants to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, the seven suspected smugglers and nine Taiwanese crewmen of Chin Lung Hsiang were detained and faced federal smuggling charges.88

In late 1994 and early 1995, Boutwell supported the U.S. intervention in Haiti known as Operation Uphold Democracy. On 22 December, Boutwell stopped the sailboat Honora 27 nautical miles east of the Virgin Islands while it was transiting from St. Martin to St. Thomas. Honora was found to be carrying 33 immigrants from China, Haiti, Colombia, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic. The immigrants were later turned over to the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. On 7 January, Boutwell helped to repatriate 289 Haitian immigrants from Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. At the time, the U.S. was attempting to clear its refugee camp at Guantanamo Bay, which housed some 20,000 refugees. Also during that patrol, Boutwell conducted military and law enforcement exercises with the cutter Nunivak (WPB-1306) and the Dominican Republic vessels Orion and Colon.89

In September and October 1995, Boutwell and the cutter Harriet Lane (WMEC-903) collected scientific data on the feasibility of the 270-foot Famous-class operating in Alaskan waters during Operation Ocean Motion. On 2 October, Boutwell stopped the FV Liberty Bay, which was found to have 10 crewmembers with falsified immigration documents. In addition, the vessel had numerous fishing violations, such as improperly maintained fishing logs. Boutwell escorted the vessel into Dutch Harbor.90

On 6 July 1996, Boutwell encountered an unflagged and unnamed fishing vessel 250 miles southwest of Attu. The vessel promptly cut her nets and ran with Boutwell in pursuit. After three days, despite numerous unsuccessful attempts to hail the vessel, Boutwell‘s small boat team picked up a message in a bottle that was thrown overboard. As the note was in Chinese, Boutwell got a translation from Coast Guard HQ saying that the boat was Chang Fu 31, a Taiwanese vessel headed home after suffering a broken freezer. As Coast Guard officials worked with the U.S. State Department and the Taiwanese government, Boutwell continued to shadow Chang Fu 31 until they were about 420 miles off the coast of Japan, where they were met by Taiwanese patrol ships. As it turns out, the vessel was actually Charngder No. 2 (sp?) and had been illegally drift net fishing for salmon. The crew was later taken into custody by Taiwanese authorities.91 In the winter of 1996, Boutwell deployed to the eastern Pacific for a counterdrug patrol. She interdicted a go-fast boat carrying 2,000 pounds of marijuana in the Gulf of Tehuantepec. The contraband and crew were later turned over to the Mexican Navy. Boutwell again attended the 1997 Portland Rose Festival in early June, and afterward participated in the search for a missing Coast Guard HH-65 Dolphin helicopter (CG6549) that was responding to a sailboat in distress 40 miles off Cape Mendocino near Humboldt Bay. Despite a three-day search covering some 70,000 sq. miles, only pieces of debris from the helicopter were recovered, with no sign of the aircrew.92

Boutwell supported Operation Border Shield in the waters off the coasts of Mexico and the U.S. Boutwell‘s embarked HH-65 helo participated in the pursuit of a go-fast that was fleeing authorities and jettisoning its cargo. While the go-fast managed to escape, the recovered cargo turned out to be 5,291 pounds of cocaine, which was later turned over to the Mexican Navy for destruction. Boutwell conducted another Alaska patrol in the fall and winter of 1997.93

In late May 1998, Boutwell coordinated with the Coast Guard cutters Jarvis (WHEC 725) and Polar Sea (WAGB 11), along with U.S. Coast Guard and Canadian Coast Guard aircraft, to interdict vessels suspected of illegal driftnet fishing. Further international assistance was provided by Russian patrol vessels and members of the Japan Coast Guard and the Chinese Bureau of Fisheries. During the operation, four fishing vessels were seized for engaging in driftnet fishing. On 28 May, Boutwell began pursuing the Chinese fishing vessel Tai Sheng, which went on for four days and covered 1,200 miles before she was stopped and boarded. The vessel was found to be using drift nets 9.4 miles in length. This turned out to be the largest driftnet case in Coast Guard history. Along with the vessel stopped by Jarvis, the crews and vessels were transferred over to the Chinese authorities in Shanghai. In October 1998, Boutwell stopped the Liberian tanker Command, which was found to be illegally dumping fuel oil into the environment based on samples previously collected from an oil slick off the Farallon Islands in September, and samples taken from Command‘s tanks. The vessel’s skipper and chief engineer were later returned to the U.S. in January 1999 to be prosecuted for violating U.S. pollution laws on the high seas.94

While on patrol in the Bering Sea on 2 April 2001, Boutwell, along with the icebreaker Polar Star (WAGB-10) searched for the missing FV Arctic Rose after her emergency locator beacon was detected 775 miles southwest of Anchorage, AK. Unfortunately, only an oil sheen, a life raft, and six empty survival suits were found. Arctic Rose was presumed lost with all 15 hands. Later, her sister ship, Alaskan Rose, managed to recover one body and located a second, but couldn’t recover it due to heavy seas.95

In early 2002, Boutwell was deployed to the eastern Pacific as part of Operation New Frontier to test counterdrug tactics using over-the-horizon small boats and armed helicopters from the Helicopter Interdiction Tactical Squadron (HITRON). On 4 February 2002, Boutwell stopped a go-fast 20 miles from Guatemalan waters, which was carrying 5,070 pounds of cocaine. On 11 February, Boutwell and Hamilton (WHEC-715), using their embarked HITRON helos, stopped another go-fast 150 miles southwest of Costa Rica and seized over 6,600 pounds of cocaine. On 12 March, another go-fast was stopped 20 miles west of Cabo San Lazaro, Mexico, carrying 1.5 tons of marijuana.96

On 3 January 2003, Boutwell departed Alameda to support Task Force 55 during Operation Iraqi Freedom. She made a stop in Hawaii to embark a helicopter and aircrew from Air Station Barbers Point and then continued to Singapore and Bahrain before joining USS Constellation (CV-64) and her battle group in the Persian Gulf on 6 February. The ships were enforcing UN Resolution 986, which was meant to stop arms and oil from being trafficked in and out of Iraq. In mid-February, Boutwell patrolled south of the Khawr al-Amaya and Mina al Bakr Oil Terminals and conducted Maritime Interdiction Operations (MIO). Her crew conducted boardings, which included inspecting cargo containers, to ensure sanctions were being adhered to. One of the vessels stopped was the North Korean-flagged tanker Al Noor, which was found to be illegally transporting Iraqi oil. The vessel was later detained in Kuwait. On 28 March, Boutwell’s embarked helo escorted the British Royal Fleet Auxiliary ship Sir Galahad carrying 200 tons of aid to Iraq. The helicopter also assessed the buoys along the Khawr Abd Allah Waterway. By the end of her deployment, Boutwell’s helicopter had logged 181 flights, and the cutter had conducted 123 boardings of various vessels as large as container ships to small dhows. Additionally, Boutwell served as the logistics hub for the four Island-class cutters deployed to the Persian Gulf. In total, 11 cutters and 1,300 active duty and reserve Coast Guardsmen were deployed to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean to support Operation Iraqi Freedom in the largest overseas deployment of Coast Guard assets since the Vietnam War.97

Returning from her Middle East deployment, Boutwell returned to conducting counterdrug patrols in the Eastern Pacific. After receiving information from an Immigration and Customs Enforcement patrol aircraft, Boutwell stopped El Almirante and Siete Mares on 7 March 2004, approximately 270 miles off the Mexico – Guatemala border, and found them to be carrying over 6,600 pounds of cocaine. In the fall of 2004, Boutwell did another counterdrug patrol and on 19 November found the Ecuadorian FV Kodiac abandoned and partially submerged. On board was more than 4,600 pounds of cocaine. Later, on 9 December, Boutwell found another partially submerged fishing vessel, the Jami, aboard which were 108 bales of cocaine. On 29 March 2005, Boutwell stopped the Ecuadorian FV Lesvos 300 miles west of Mexico and seized over 9,900 pounds of cocaine. On 17 April, Boutwell stopped the Venezuelan-flagged FV Isis and discovered over 7,000 pounds of cocaine. Boutwell delivered supplies to Tocumen, Panama, on 31 December 2005, and the crew assisted in painting classrooms and repairing wiring at the Escuela Fuente de Amor. On 16 January 2006, Boutwell, her embarked HITRON helo, along with the frigate USS De Wert (FFG-45) and its embarked Law Enforcement Detachment (LEDET) 406, stopped two go-fasts carrying over 5,300 pounds of cocaine. The drugs and 12 crewmembers were turned over to Colombian authorities.98

On 24 August 2006, Boutwell interdicted the FV Mi Panchito and confiscated more than 14,770 pounds of cocaine. On 12 September, she stopped a go-fast 120 miles west of Puerto Quetzal, which was carrying some 6,400 pounds of cocaine. On 17 September, Boutwell stopped a go-fast 460 miles northeast of the Galapagos Islands and seized 1,300 pounds of cocaine. On 17 October, she stopped the Ecuadorian FV Ludemar and confiscated 200 pounds of cocaine. In total, she seized nearly 23,000 pounds of cocaine in four different cases and apprehended 16 suspected smugglers during that patrol.99

On 22 July 2007, Boutwell departed on an Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fisheries enforcement patrol in the High Seas Drift Net (HSDN) High Threat Area. This was a multinational effort as part of the North Pacific Coast Guard Forum involving members of China, South Korea, Japan, Russia, Canada, and the United States. The cooperation between the countries was meant to bolster efforts in 2007 to enforce the UN General Assembly’s 1991 resolution against high seas drift net fishing in the Pacific. On 2 September, Boutwell stopped Lu Rong Yu 6007 for illegal high-seas driftnet fishing and turned the vessel over to the Chinese on the 13th. On 14 September, she stopped the Indonesian FV Fong Seng No. 818. Ten days later, on 24 September, Boutwell stopped Zhe Dai Yuan Yu 829 and found evidence of drift nets aboard. On 1 October, Boutwell intercepted Lu Rong Yu 1961, which was engaged in drift net fishing. Both this vessel and Zhe Dai Yuan Yu 829 were later turned over to Chinese authorities. On 5 October, Boutwell seized Lu Rong Yu 2659, Lu Rong Yu 2660, and Lu Rong Yu 6105 for the illegal drift net fishing of 80 tons of squid. The three ships were later transferred to Midgett (WHEC 726), who then turned them over to the Chinese.100