World War II in the Pacific ended on a somewhat anticlimactic note, at least at sea. The Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944 saw the Imperial Japanese Navy being crushed as an effective fighting force and they never again mounted a significant offensive operation. Operation Ten-Go was the last suicidal sortie of the battleship Yamato, which was sunk by a large air strike, and with the conclusion of the Battle of Okinawa in June 1945, there were still two months of hostilities. As planning for Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of Japan, was underway, the U.S. Navy’s submarine force was still hard at work patrolling the waters of the Pacific and enforcing a naval blockade on Japan, just as it had been doing since the United States entered the war back on 7 December 1941.

While the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively, generally signaled the end of the war, it would still be six more days before Japan’s leadership would announce capitulation. As it turns out, those six days would see some of the final shots of the war; some of which came from a submarine.

The Last Combatants

The final submarine battle of WWII was fairly conventional by most standards. It involved a submarine and a few surface ships. The combatants were as follows:

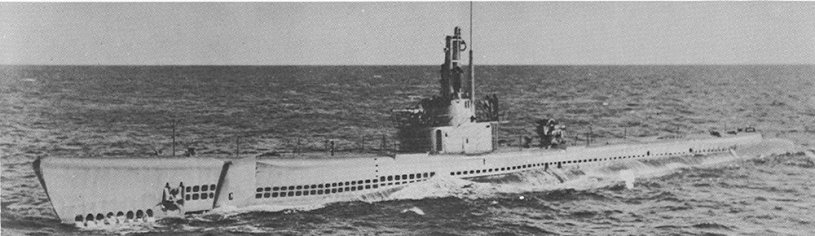

USS Torsk (SS-423) is a Tench-class submarine. Her WWII career was fairly short, as she was commissioned in December 1944 and only did two war patrols before the war ended.

Tench-class Characteristics

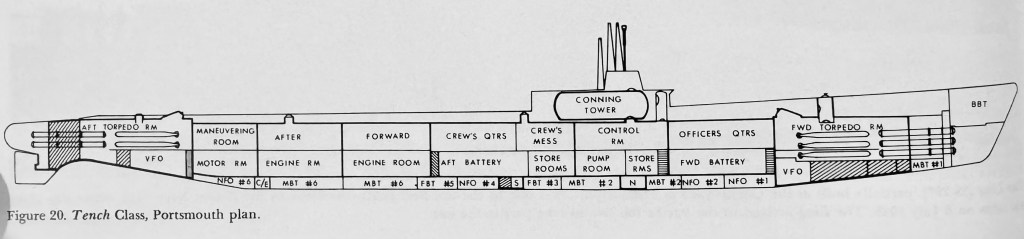

The Tench-class submarines were a further refinement of the previous Balao-class with rearranged fuel and ballast tanks. Additionally, they had the latest models of machinery and equipment, and notably, new slow-speed, direct-drive electric motors which eliminated the need for bulky reduction gears. Externally, the Tench-class was virtually identical in appearance to the Balao-class, except for a sharper knuckle at the base of the stem. That said, they were generally equal in performance to the Balao-class.1

| Displacement | 1,570 tons surfaced (standard), 2,415 tons submerged |

| Dimensions | 311 ft. 8 in. length (overall) x 27 ft. 3 in. beam |

| Depth | 400 ft. (test depth) |

| Powerplant | 4x Fairbanks-Morse 38D 8-1/2 10-cylinder diesel engines (5,400 shp) powering 4x General Electric main generators. 1x Fairbanks-Morse 35A5-1/4 7-cylinder aux. diesel engine. 2x General Electric main electric motors (2,740 shp). 2z 126-cell batteries. 2 shafts. |

| Speed & range | 20.25 kts. surfaced, 8.75 kts. submerged. 11,000 nm at 10 kts. |

| Armament | 1x – 2x 5″/25 deck guns. 6x bow & 4x stern torpedo tubes (28 torpedoes max). 40x mines max. (with 2x mines in place of 1x torpedo). |

| Crew | 81 |

Type C Kaibōkan Characteristics

Kaibōkan (海防艦, lit. “sea/ocean defense ship”) were several classes of small coastal defense and escort ships used by the Imperial Japanese Navy late in the war. Roughly equivalent in firepower and role to destroyer escorts, frigates, or Coast Guard cutters.

With unprotected merchant ship losses mounting, Japan sought to rapidly increase the production of its escort forces. Ordered under the 1943 – 44 and 1944 – 45 building Programmes, the Type C Kaibōkan was a simplified variant of the earlier Ukuru Type (AKA modified Type B escorts). Electric welding was used in the construction of the hull and sections of the vessel were prefabricated to increase production speed. The result was a vessel that could be built in as little as three months, although a lack of materials often meant construction times were as long as eight months. The Type Cs were constructed at various yards, including Mitsubishi; Kobe; Tsurumi; Nihonkai Dock; Tayama; Maizuru Dockyard; Naniwa, Osaka; and Kyowa, Osaka. In a change from the earlier Ukuru Type, the Type C featured a lower funnel and longer foc’s’le. While still diesel-powered, they had less horsepower than the previous Ukuru-class, at 1,900 bhp which resulted in a three-knot decrease in top speed to 16 knots. This was barely enough to allow the Type Cs to keep up with a merchant convoy or chase submarines. Still, they were regarded as very seaworthy, although ballast had to be added to the stern to trim the vessel out and prevent the bow from plunging into the waves.3

| Displacement | 745 tons |

| Dimensions | 221 ft. 6 in. length (overall) x 27 ft. 6 in. beam x 9 ft. 6 in. draft |

| Powerplant | Diesel engines (1,900 bhp), 2 shafts. |

| Speed & range | 16.5 kts. max, 6,500 nm at 14 kts. |

| Armament | 2x 4.7″ DP guns 6x 25mm AA guns (in 2 triple mounts) (increased to 12x to 16x 25mm in 1944 – 45) 1x 3″ trench mortar 12x depth charge throwers (120 depth charges) |

| Crew | 136 |

Torsk‘s Last War Patrol

At the start of August 1945, USS Torsk departed Guam for her second war patrol. On 10 August, she used her FM sonar to detect mines and pass through the Tsushima Strait and into the Sea of Japan. The next day (11 August) Torsk rescued seven Japanese merchant seamen clinging to a liferaft. Their cargo ship, Koue Maru, had been sunk several days earlier by U.S. aircraft. Torsk continued on to her patrol area; entering it that afternoon.5

At 0830 on 12 August, Torsk was submerged at periscope depth and torpedoed a small coastal freighter near Dogo Island; scoring her first kill of the patrol. The following day (13 August), Torsk sank the freighter, Kaiho Maru, and pursued a larger cargo vessel that managed to escape to the safety of Wakasa harbor.6

On the morning of 14 August, Torsk sighted a larger cargo ship off the town of Amarube accompanied by the Kaibōkan No. 13 escort vessel and pursued it as it headed east. A further three miles east, as the freighter approached the town of Kasumi, Hyogo, Torsk fired a Mk 28 acoustic homing torpedo at the escort at 1035. The torpedo successfully hit and blew the stern of Kaibōkan No. 13 up at a 30-degree angle. She sank shortly after at 35°41’ North, 134°35’ East.7 The merchant ship she was pursuing escaped to the safety of a nearby harbor about a half hour later. Reportedly, Torsk attempted to torpedo this merchant ship while she was in the harbor, but the torpedoes struck a shallow reef. Around 1200, another escort vessel, Kaibōkan No. 47, approached and located Torsk on her sonar. Torsk fired a Mk 28 torpedo at her (which ultimately missed), dove to 400 feet, and initiated silent running. Torsk then fired two Mk 27 “cutie” torpedoes on sonar bearings at the Kaibōkan. At 1225, lookouts on Kaibōkan No. 47 spotted the torpedo wakes and attempted to take evasive action. Reportedly, one torpedo found its target and exploded against the ship’s stern, where she developed a starboard list and sank at 35° 42′ North, 134° 36′ East ten minutes later.8

Note: There are some discrepancies between sources regarding the freighter Torsk was pursuing, the types of torpedoes fired, the order in which the escorts were sunk, and the positions of their sinking. See below for further analysis.

For the next seven hours, Torsk was held down by aircraft and other escort vessels before she was able to escape. After surfacing, she headed for the Noto Peninsula, further northwest.9 The following day (15 August), Emperor Hirohito went on the radio and announced to the Japanese people that they would have to “bear the unbearable.” Japan had finally surrendered.

Torsk remained on patrol in the Sea of Japan until 3 September when she passed back through the Tsushima Strait and set a course for the Marianas, arriving at Guam on the 9th, and completing her second (and final) war patrol. Torsk‘s service continued after the war. She underwent a fleet-snorkel conversion in 1952 which, unlike other submarines that received the more expensive GUPPY conversion, was a very austere conversion and involved providing snorkels and streamlined sail structures to the subs.10 Torsk‘s postwar service also included several deployments to the Mediterranean and she was decommissioned on 4 March 1964. She currently sits in Baltimore, Maryland where she has operated as a museum ship since 26 September 1972.11

Thus, Torsk fired the last torpedo shots of WWII and became the last U.S. Navy submarine to fire torpedoes in anger (thus far).12

Discrepancies between sources

There are several differences in the narratives about the events on 14 August depending on what source is used. The identity of the freighter Torsk was pursuing on the 14th is unknown. Kimmett and Regis imply that this was the same ship that Torsk was pursuing the previous day which had escaped to Wakasa Harbor.13 However, Wakasa Harbor and Maizuru are nearly 40 miles away from the towns of Amarube and Kasumi, as the crow flies. While the freighter may have returned to that area on the 14th, no source mentions the name of this vessel, the direction it was traveling in, or its destination. In all likelihood, it was a different merchant ship.

Regarding what types of torpedoes Torsk fired at the escorts on the 14th, Kimmett and Regis write that only Mk 27 “cutie” torpedoes were used.14 Conversely, the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships notes that Mk 28 torpedoes were fired at both Kaibōkans and sank the first one, but missed the second. These were followed by a Mk 27 that hit and sank the last Kaibōkan.15 Similarly, Hackett, Kingsepp, and Cundall, in the Tabular Record of Movement (TROM) for Kaibōkan No. 47 write that Mk 28s were fired at both Kaibōkans and sank No. 47, but missed No. 13. However, the two Mk 27s that were later fired at No. 13 both hit and sank it.16 On the other hand, the TROM for Kaibōkan No. 13 records that only one Mk 27 hit No. 13, and Kimmett and Regis similarly write that the last Kaibōkan sank was hit by only a single torpedo.17

The order and position in which the Kaibōkans sank are also disputed. Both TROMs from combinedfleet.com note that No. 47 was sunk first followed by No. 13.18 In contrast, Kimmett and Regis say that Kaibōkan No. 13 was sunk first.19 The following table shows the coordinates of their sinkings given by different sources:

| Combinedfleet.com TROMs (Hackett, Kingsepp, & Cundall) TROM for Kaibōkan No. 13 Kaibōkan No. 47 35°42’N, 134°36’E Kaibōkan No. 13 35°41’N, 134°35’E TROM for Kaibōkan No. 47 Both 35°41’N, 134°38’E |

| Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869 – 1945 (Jentschura, Jung, and Mickel) Both 35°41’N, 134°38’E |

| Wikipedia Articles Japanese escort ship No. 47 Kaibōkan No. 47 35°41′N 134°38′E from The Official Chronology of U.S. Navy in World War II Japanese escort ship No.13 Kaibōkan No. 47 35°42′N 134°36′E from combinedfleet.com No. 13 TROM Kaibōkan No. 13 35°41′N 134°35′E from combinedfleet.com No. 13 TROM The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II Kaibōkan No. 47 35°41’N, 134°38’E Kaibōkan No. 13 35°44’N, 134°38’E |

Strangely, as seen in the above table, the TROM for No. 47, the Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II, the Wikipedia article for No. 47, and Jentschura, Jung, and Mickel’s Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869 – 1945 note that either Kaibōkan No. 47, or both ships, were sunk at the exact same coordinates as indicated by the green marker on the map. It’s highly unlikely that both ships were sunk in the exact same spot. The TROM for No. 13, as well as the Wikipedia article for Kaibōkan No. 13, gives different coordinates for both ships as shown by the red markers on the map. I’ve gone with these positions above in my narrative. Finally, the Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II gives No. 13’s position as further north of all of them, as shown by the blue marker on the map. Realistically, unless these wrecks have been surveyed in the modern era, it’s probably worth taking these coordinates with a grain of salt since navigation in the 1940s wasn’t nearly as accurate as it is today. At the very least, all sources agree that the escorts were sunk in this general vicinity.

Notes

1. Alden, John Alden, The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), 108.

2. Alden, 108.

3. A.J. Watts and B.G. Gordon, The Imperial Japanese Navy (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971), 390 – 391; Hansgeorg Jentschura, Dieter Jung, and Peter Mickel, Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869 – 1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982), 189.

4. Jentschura, Jung, & Mickel, 190.

5. Larry Kimmett and Regis, Margaret, U.S. Submarines in World War II: An Illustrated History (Kingston, WA: Navigator Publishing, 1996), 130.

6. “Torsk (SS-423),” Naval History and Heritage Command Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, April 25, 2016, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/t/torsk.html. Hereafter referred to as DANFS; Kimmett & Regis, 130.

7. Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-13: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com, 2019, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-13_t.htm.

8. DANFS; Kimmett & Regis, 130; Bob Hackett and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-47: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com. 2018, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-47_t.htm; Jentschura, Jung, & Mickel, 190.

9. DANFS.

10. Alden, 152.

11. DANFS.

12. U.S. submarines have fired live torpedoes during exercises (such as a SINKEX) since the war, but never at an enemy target. Additionally, submarines have fired Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles at enemy targets during conflicts such as the Gulf War, Balkans, Sudan, Iraq, and Afghanistan, but Torsk fired the last torpedo in combat.

13. Kimmett and Regis, 130.

14. Kimmett and Regis, 130.

15. DANFS.

16. Bob Hackett and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-47: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com. 2018, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-47_t.htm.

17. Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-13: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com, 2019, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-13_t.htm; Kimmett and Regis, 130.

18. Bob Hackett and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-47: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com. 2018, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-47_t.htm; Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp, and Peter Cundall, “IJN Escort CD-13: Tabular Record of Movement,” http://www.combinedfleet.com, 2019, http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-13_t.htm.

19. Kimmett and Regis, 130.

Bibliography

Alden, John. The Fleet Submarine in the U.S. Navy. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979.

Hackett, Bob, and Peter Cundall. “IJN Escort CD-47: Tabular Record of Movement.” http://www.combinedfleet.com. 2018. http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-47_t.htm.

Hackett, Bob, Sander Kingsepp, and Peter Cundall. “IJN Escort CD-13: Tabular Record of Movement.” http://www.combinedfleet.com. 2019. http://www.combinedfleet.com/CD-13_t.htm.

Jentschura, Hansgeorg, Dieter Jung, and Peter Mickel. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869 – 1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982.

Kimmett, Larry, and Margaret Regis. U.S. Submarines in World War II: An Illustrated History. Kingston, WA: Navigator Publishing, 1996.

“Torsk (SS-423).” Naval History and Heritage Command Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. April 25, 2016. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/t/torsk.html.

Watts, A.J., and B.G. Gordon. The Imperial Japanese Navy. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971.