This is also a segment of the Down Periscope, Up Periscope: Tales of Submarine Tours Podcast.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the presenter’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of either the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry or the United States Government. While strong efforts are made to ensure accuracy, all information is subject to change without notice. As such, all personal statements, opinions, omissions, and errors are the commentators’ own.

Like a sardine can…

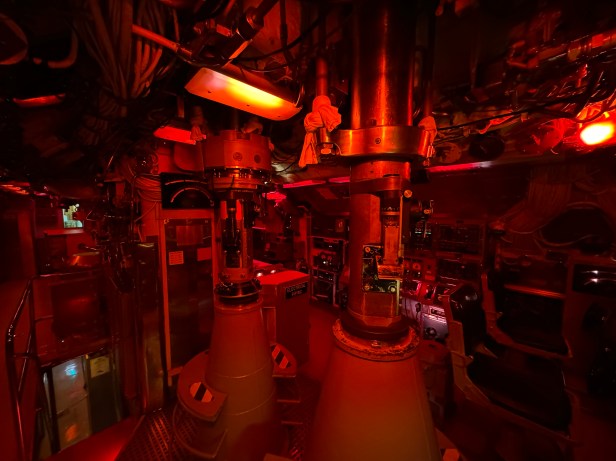

Despite what you see in movies (or video games), Navy submarines are not roomy. They’re cramped, industrial environments, and not very comfortable. Everywhere you look, the bulkheads and overheads are covered with pipes, wires, buttons, valves, switches, and equipment; much of which is hard, and occasionally sharp. There are hatches and cabinets all over the place, even on the deck, which open up to reveal storage spaces. The inside of a fast-attack submarine, such as USS Blueback (SS-581), is the literal definition of “zero personal space.”

Even inside the enormous ballistic missile submarines (AKA boomers), most of the spaces are filled with equipment and designed around supporting the main weapon systems; in this case, the nuclear ballistic missiles. At times, it seems like the human factors were almost an afterthought in the design of submarines. Then again, we’re talking about the U.S. Navy and not a cruise line.

Compare the above images to the ones below from the 1995 film Crimson Tide, which takes place on the ballistic missile boat, USS Alabama (SSBN-731).

The film’s production crew briefly went aboard USS Florida during pre-production; however, the U.S. Navy withdrew support once they found out that the film depicts a mutiny aboard a submarine. The film sets were built on large gimbals which allowed the set to tilt back and forth and simulate the submarine changing angles. The inspiration for the interior sets is apparent, as the overall layout looks similar, but there’s more room (and moody lighting) on the film set. Apart from general ignorance of how submarine interiors look, much of the added space on film sets is to allow for the camera equipment and crew. That’s why submarines in movies look so spacious. The possible exceptions to this would be Das Boot (1981), Phantom (2013), and Hunter Killer (2018), as those movies were filmed aboard actual submarines or the sets were meticulously recreated.

Do submariners get claustrophobic?

The submarine service in the U.S. Navy is selective and all volunteer. For enlisted sailors, the training involves 2 months at Basic Enlisted Submarine School (BESS) which teaches them the fundamentals of submarine operations. Basically, just enough to be dangerous. During BESS, students go through three damage control trainers to simulate three specific casualties. These are the firefighting, flooding, and submarine escape trainers. The flooding trainer (AKA wet trainer) is a mocked-up engineering space with leaking pipes that cause the room to slowly fill with water. Students are tasked with coordinating with each other and plugging the leaks. As the water level rises, more pipes begin to leak because it’s actually controlled from a control room, and the water begins to rise faster; simulating the submarine increasing depth, and therefore, the outside pressure is increasing. The room can also be blacked out, simulating a loss of electrical power and forcing students to work in the dark with only flashlights and battle lanterns.

Of course, it’s a training environment, and the instructors will stop the exercise before anyone actually gets hurt. Still, should the students fail, there will be strong admonishments to drive the point home that they didn’t work together to stop the flooding in time. As a result, the submarine has now sunk, and everyone is theoretically dead.

BESS also includes physical and psychological screenings to make sure students are capable of serving on submarines. Certain physical and psychological conditions are disqualifiers. Obviously, anyone with claustrophobia would do well to steer clear of submarines (and the Navy, in general).

Seeing photos is one thing, but imagine living and working on a submarine for months at a time. Say, for example, that your boat is going on a Western Pacific Cruise (WESTPAC). That’s one 2 – 3 month-long patrol. Then the submarine will pull into port, reprovision, and you’ll get a chance to see the sun again. Then the submarine will go out on another 2 – 3 month-long patrol before you get back to your homeport. That’s basically 4 – 6 months away from home, in a giant steel tube with no privacy (except your rack when you sleep), with more than 100 of your not-so-closest friends.

Despite all the training and screenings, some submariners have been known to get cabin fever.

Featured Tour Guide – Robert Talbert – ETV1, U.S. Navy

Our featured tour guide is Robert Talbert, a former Electronics Technician (Submarine Navigation), First Class (ETV1). While his rating would imply something to do with navigational equipment, his job wasn’t to directly navigate a submarine (that’s what a Quartermaster does), rather his job was to make sure the ballistic missile navigation systems worked and the missiles “knew” where they were so they could be accurate and hit their targets. One of Blueback‘s volunteer tour guides, he spent his submarine service aboard boomers in the Atlantic Fleet.

Robert is a friendly, soft-spoken man who is instantly recognizable among the volunteer guides because he often wears his service dress blues (AKA sailor suit, the blue jumper, or cracker jacks). In short, he definitely looks like a sailor. Robert travels around the U.S. and has been a tour guide at numerous other submarine museums, in addition to USS Blueback at OMSI.

Transcript

Tim

Hello everyone, my name’s Tim and welcome back to the Down Periscope, Up Periscope Podcast. I’m your host and today we have another guest speaker. We have Robert Talbert, a former submarine veteran.

Now, a question I get asked every so often on my tours is, “do people get claustrophobic on a submarine?” Well, it has been known to happen, and speaking of that Robert has a quick story on that. Robert, why don’t you tell us?

Robert

Hello. Robert Talbert.

Yes, it was odd. My last ballistic missile patrol, [on] a big ballistic missile boat. We were under for about two months and I started getting this feeling that I was gaining too much weight from all that good chow. And I kept thinking about it, kept thinking about it, and [I thought] can get through that hatch at the end of the patrol? That’s when it hit. The claustrophobia.

Can I get out of that hatch? And I had to convince myself; I had to think it through, ‘cause we weren’t coming back in just for that. Would I ever get the size of a 24-inch diameter? No, it was bigger than that. Those were about 3-foot in diameter…those hatches. And I had to think it through and logically decide that there is absolutely no way that I could gain that much weight.

After about a week, I finally talked myself down. Didn’t tell anybody about it; that would’ve been a bit embarrassing, but yes, you can get claustrophobic on a submarine. Even a ballistic missile boat.

Tim

Indeed, and what boat was this on?

Robert

This was on the [USS] Nathanael Greene.

Tim

As they say, you go through a lot of psychological testing, especially at submarine school, to see…I mean, if you’re claustrophobic, then being on a submarine is probably not for you. But here you have it, from a guy who was on submarines, it can happen. Indeed, it does. So it took you about a week to kind of talk yourself out of it?

Robert

It did. It did.

Tim

Did it feel like the walls were kind of closing in on you, or anything? Or you were just concerned about the diameter of the hatch?

Robert

The walls, yes. Could I get back out? It was just crazy, and I had to use my logical mind to talk myself down. Could I get out of the boat?

Tim

Normally, you’re not claustrophobic?

Robert

Oh, no, no. Like you said, in submarine school, we went through the training. We did the emergency ascent for 50-foot, after being closed up in a small chamber with about eight of us, with the water up to our nose. That didn’t do it. About 50 of us inside of a pressure chamber. That didn’t make me claustrophobic. It was very, very annoying.

Tim

Well, apparently, sometimes it just gets to you.

Robert

Yes.

Tim

Well, thank you for that story, Robert.

Robert

Thank you.

[End of Interview]

Claustrophobia on Blueback Tours

Visitors occasionally ask why the submarine is so cramped. My response is: well, it’s a warship, not a cruise ship. Everything in the boat is designed to support the combat systems. Sonar, Electronic Support Measures (ESM), Electronic Countermeasures (ECM), radar, fire control, various transmitters and receivers, propulsion, and even the torpedoes themselves constitute a multitude of systems around which the hull is built. Human factors are somewhat secondary and believe me, navies out there are researching and developing Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), which like Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), don’t require humans to physically be on them. Whether or not UUVs will eventually replace manned warships and submarines is debatable, since we still haven’t gotten rid of manned aircraft. Still, if you read any design histories of these vessels (e.g. Norman Friedman has an excellent series of books on naval warship design), then you can see that they’re designed to fulfill a certain set of missions, none of which involve traipsing around the Caribbean on a pleasure cruise.

Another question I often get is regarding whether or not there’s a height restriction on submarines. To my knowledge, there is not. The tallest sailor on Blueback was 6 foot 8 inches. He walked around hunched over the whole time. If there is a body restriction, it’s probably a girth restriction, as Robert mentioned. You have to be able to fit through the 25-inch diameter hatches to get in and off the submarine, and you have to be able to move quickly through the submarine in an emergency. Put another way: if you’re too tall to stand up straight on a submarine; that’s your problem, but if you can’t fit through the hatches to get in and out of the submarine quickly in an emergency, that becomes everyone‘s problem.

The enlisted crew’s berthing racks (beds) are all a standard size. 6 feet 2 inches long and 2 feet wide, with 1 and 1/2 feet of vertical clearance between them. This gives an enlisted crewman slightly less than 18.5 cubic feet to sleep in and is their only area of privacy for 6 hours in an 18-hour day when this submarine was in operation, anyway. (U.S. submarines changed to a three 8-hour watch 24-hour day in 2015.)

Officers have the same size beds but sleep in nicer 3-man staterooms, which are still crowded. The sole exception to this is the commanding officer. He’s the only person with guaranteed privacy and has the biggest stateroom with a single rack all to himself. His rack is also the only one that you can sit up in and not bash your head against anything. As is customary in the sea service, the captain will not share his stateroom with anyone, even visiting dignitaries. It doesn’t matter if you’re Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz or the President of the United States…the captain gets his own stateroom. In fact, if you are a visiting dignitary, then the Executive Officer’s (XO’s) stateroom has a fold-down rack from the overhead, and he’ll share his cabin with you.

As I mentioned in Season 1, episode 3, I’m not particularly claustrophobic, unless the spaces get really tight. Still, there are some places on Blueback that I don’t particularly like to go. These would be the lower engine deck, the auxiliary machinery space, and the pump room. Mostly because those spaces are dirty and they’re filled with hard and sharp objects. If you move a foot or two in the wrong direction, part of you (such as your face) will make contact with one of those hard and sharp objects. Even then, I hardly ever have a reason to go into those spaces, and I’ve never served on an operational submarine, so I’ve never had to deal with the confinement of being trapped on one for months at a time. On Blueback, I still have the option of stepping outside of the boat onto dry land for fresh oxygen.

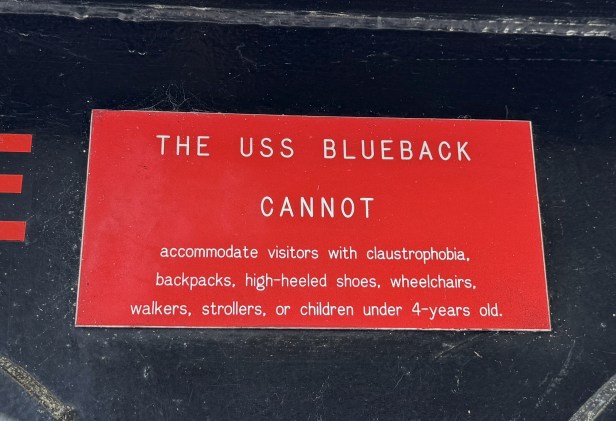

As a museum ship with the interior largely unaltered from her original design, Blueback can’t accommodate visitors with various conditions. For example, those who are wheelchair-bound or on strollers will simply not be able to access the submarine because there’s no wheelchair ramp. Before the tour, visitors go through a safety briefing and have to demonstrate that they can pass unassisted through a mock-up of one of the watertight hatches.

The watertight hatch is a 20-inch by 38-inch oval, and there are two of these in the sub, located at the watertight pressure bulkheads at frames 24 and 52. These doors are hydrostatically tested to withstand up to 377 psi before they’re unseated. If you can’t pass through this opening, then you’ll have trouble getting through the boat. It’s the narrowest door you’ll pass through, and those with severe claustrophobia will probably not do well within the confined spaces of the boat anyway.

That said, I’ve seen blind people, quadruple amputees (with prosthetic legs), and even people with claustrophobia (to some degree) make it through the entire boat on a tour. (Yes, really!) I’ve even had claustrophobic people on my tours, as well; however, it didn’t seem to be a debilitating condition, and they made it through the tour.

Another thing is that small children (many of whom are 3 – 6 years old) are often uncomfortable on the submarine, and the reality seems to hit them once they step aboard and proceed down the stairs at the entrance to the boat. The stairs are steep and children sometimes have trouble navigating them. Many of them say that they’re scared and they aren’t really prepared for the enclosed spaces. We tour guides have speculated that these children are likely claustrophobic themselves, but they don’t realize it yet because they’re so young. Other areas of the boat, such as the control room, are dimly lit because they’re “rigged for red” with red lighting to simulate darkened conditions. Since they’ve never been in this kind of environment, the darkened areas can seem a bit spooky to small children. As such, they can really become freaked out and scream to their parents about how scary the boat is. If it gets bad enough, the parents often elect to remove their kids from the tour.

Another time, I witnessed a particularly claustrophobic visitor come aboard for a tour (not mine), and upon stepping aboard, this woman informed her tour guide that she was extremely claustrophobic, but would try her best to get as far as she could through the tour. Once in the wardroom (the first stop inside the boat), the tour guide mentioned that the entire tour group was now partially underwater, with their lower legs essentially being submerged. Upon hearing that little factoid, this woman took off like a shot, ran back up the stairs, and exited the boat. She only lasted about one minute on board. Thankfully, there was no dramatic freakout. She just quickly and quietly exited.

On one hand, I feel for her, but I must admit that it was a bit amusing to watch, as I was off to the side observing this happening. The claustrophobia of this woman was clearly intense as if the mere mention of being partially submerged in a steel tube was enough to make her flight or flight response kick in. Again, Blueback isn’t going anywhere, but two-thirds of the submarine’s hull (~20 feet) is below the water. Without the hull, when you step on board, your feet and ankles would be wet.

In the end, I honestly have to question the logic of some of these people. On one hand, I applaud them for facing their phobia and not letting it hinder them from coming aboard for a tour, if it satisfies their curiosity. Obviously, their condition, be it claustrophobia or whatever, isn’t severe enough to stop them. Yet, on the other hand, what do they think Blueback is, a Carnival cruise ship or something? Pictures or videos online don’t really do the environment justice. It’s more cramped than it looks. So, if you’re claustrophobic, to begin with, then being on a submarine probably isn’t for you. Still, as Robert testified, even trained submariners can get claustrophobic at times.