When you think of the U.S. Coast Guard, you probably picture the large white cutters with their distinct red racing stripe, or perhaps you’ve seen one of their helicopters fly over a beach. Maybe you’ve even witnessed a motor lifeboat struggling through the surf. But did you know that at one time, the U.S. Coast Guard operated hovercraft? This is the brief story of three of the most peculiar vessels used by the U.S. Coast Guard.

| Vessel | Year |

|---|---|

| 38101 – 38103 | 1969 (USN) October 1970 December 1970 February 1971 (USCG) |

Characteristics

| Displacement | 20,000 lbs. (full load) |

| Dimensions | Length: 38′ 10″ overall Beam: 23′ 9″ max Height: 15′ 11″ Obstacle Clearance (in 1971): 3′ 6″ solid wall, 5 – 6′ vegetation |

| Powerplant | 1x General Electric LM100 gas turbine (1,150 shp) 1x propeller |

| Performance | 70 kts (max), 50 kts (max sustained) |

| Range | 300 mi. radius (1971), 484 gal. kerosene |

| Sensors | 1x surface navigation radar |

| Crew | 3 (Operator, Radar/Navigator, SAR crewman) |

Design

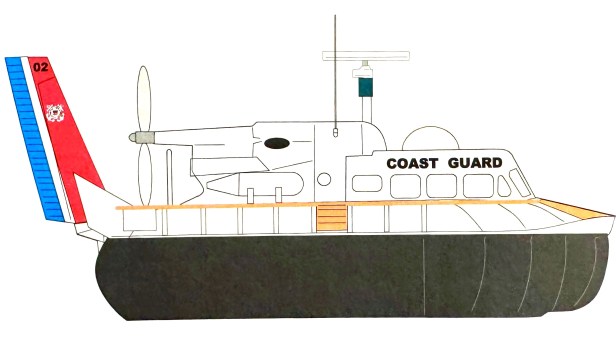

Developed in the 1960s, these hovercraft were originally the Saunders-Roe SR.N5, sold as the Bell SK-5 under license.4 They are powered by one General Electric LM100 gas turbine engine producing around 1,150 shp. Thrust is provided by a four-bladed, variable-pitch propeller, and a seven-foot centrifugal lift fan generates the air cushion. Both the propeller and the lift fan operate off the same engine.5 A version for the U.S. military was modified to include a flat deck, a gun turret, and a grenade launcher for armament. Used by the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy as the Patrol Air Cushion Vehicle (PACV), three went to the Army, and three went to the Navy. These vehicles were sent to Vietnam for trials and mainly used in the Mekong Delta in the Plain of Reeds.6

Coast Guard Service History

In the late 1960s, the U.S. Coast Guard began a program to test the feasibility of using air-cushioned vehicles for their search and rescue, aids to navigation, law enforcement, marine safety, and navigation missions.7 Since the Navy no longer required the three they had for service in Vietnam, they were given to the Coast Guard for evaluation in 1969 and overhauled the following year. In Coast Guard service, the crew consisted of an operator, a radar operator/navigator, and a search-and-rescue crewman, plus space for six passengers or an appropriate amount of cargo. Two were stationed at the Fort Point Coast Guard Station in San Francisco, California, in October 1970. The third one was assigned to Point Barrow, Alaska, for arctic trials.8

Operational evaluation at Fort Point began on 1 January 1971 under Commander Thomas C. Lutton, USCG. Over eight months, 1,400 hours of formal testing were conducted in various Coast Guard missions. Overall, the ACV provided unique capabilities for SAR cases, creating a highly effective response team when paired with aircraft and boats. In law enforcement missions, the high speed of the ACVs (not possible in small boats) made evasion difficult. The ACVs also made routine maintenance of Aids to Navigation (ATON), as well as logistics missions, much more efficient when compared to other vessels. The only downside was that a larger hovercraft would have been needed to move an ATON or carry more cargo for logistics missions.9

As for the one assigned to Point Barrow, Alaska, the Naval Ship Research and Development Center, acting under the direction of the Department of Defense, requested that the Coast Guard operate the ACV from the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory. A series of performance tests was conducted on the snow and ice of the lagoon east of Barrow, and additional tests in the summer evaluated its performance over the tundra and open water. On 1 August, it operated in coordination with the icebreaker USCGC Northwind, helping to transfer personnel and supplies between the icebreaker and a base camp. It was also fitted with sounding equipment and an electric winch to carry out observation probes of the ice. All in all, the ACV performed its arctic missions extremely well, but despite its utility, it could not replace the current role of shipboard helicopters in the region. This ACV was later transferred to Traverse City, Michigan, for testing on the Great Lakes during the winter out of Saint Ignace Station. Further operations were conducted in the Chesapeake Bay area.10

The Coast Guard’s Final Decision

The Coast Guard recognized that the ACVs could substantially augment the operations of boats and aircraft, providing better response times at less cost. However, it ultimately decided not to procure the hovercrafts. The report concluded that the ACVs possessed several limitations not present in existing craft and thus would not replace the utility of boats and aircraft, despite their excellent performance in various missions. Additionally, they would need to procure more advanced and expensive hovercraft to carry out their missions. Still, the service was in the process of upgrading its boats and cutters, as well as purchasing new aircraft and the infrastructure to operate them. Ultimately, budgetary and project priority concerns resulted in the ACVs being transferred out of the Coast Guard.11

On 25 April 1975, 38101 and 38102 were transferred to the U.S. Army Mobility Equipment Research & Development Center. 38103 later sank in an accident.12 Thus ended the U.S. Coast Guard’s brief experiment with hovercraft.

Evaluation

These were three unique craft operated by the U.S. Coast Guard in the 1970s, even if they were never formally used in anything other than trials. Still, hovercraft have strengths and limitations. They excel in amphibious operations with their ability to move over a wide range of different terrains. Since they glide over a cushion of air, hovercraft are generally considered more environmentally friendly, as there is less risk of damaging marine animals and the environment when operating them. That said, while fast, they can be pushed around by heavy winds and do not do well in heavy seas. Reportedly, the controls of a hovercraft are fairly simple to operate, but they require some training to learn how to handle them adeptly since their movement feels frictionless. Hovercraft also struggle with steep inclines, and any significant weight must be distributed properly. Large hovercraft, especially those with multiple engines, produce considerable noise. Finally, a hovercraft’s skirt is prone to wear and tear and could be a potential weak point in the vehicle during combat operations.13 Failure of the skirt would effectively disable it.

In this author’s opinion, the U.S. Coast Guard using hovercraft would be a little strange to see. While certainly useful over a wide range of terrain, their limitations in high winds or heavy seas could be a factor when conducting search-and-rescue operations, unless the seas are relatively calm or the terrain, such as ice, mud, or swamps, prevents other assets (boats or helicopters) from approaching survivors. The loud noise of the turbine, propeller, and lift fan might also make rescues or law enforcement boardings difficult for personnel. Then, of course, there’s a question of whether or not these are classified by the Coast Guard as aircraft or boats.14 They glide on a cushion of air, and the article from Coast Guard Aviation History mentions the dates they first “flew,” but they also float on the water when the skirt is deflated. Therefore, do they need aviators or a coxswain at the controls? (I’m being somewhat facetious here.)15

Other Operators

While the U.S. Coast Guard chose not to operate hovercraft, in general, other services have found utility with them. Since the late 1980s, the U.S. Navy has continued to operate Landing Craft Air-Cushion (LCAC) vehicles in logistics roles. These are large hovercraft used to transport personnel and equipment ashore.

Other countries also use hovercraft in both commercial and military roles. Foreign versions of LCACs see use in logistics roles, and the Canadian Coast Guard also used a larger version of the SR.N5, known as the SR.N6, the last one was decommissioned in 1998.15 One is reportedly seen in the 1995 Stanley Tong film, Rumble in the Bronx, starring Jackie Chan. The SR.N6 is dressed up as a tourist boat and Jackie Chan’s character, Ma Hon Keung, engages in a long chase with it near the end of the film, including being dragged behind it and later run over by it. While the film was set in the Bronx, NY, it was actually filmed in Vancouver, British Columbia. Hence the appearance of a Canadian Coast Guard hovercraft.

Currently, the Canadian Coast Guard operates four 28.5-meter-long medium-sized hovercraft for search-and-rescue, aids to navigation, and icebreaking duties. Four more are expected to enter service by 2030.16

Given the unique capabilities of hovercraft, their utility is broad-ranging but comes with drawbacks. Obviously, no Navy or Coast Guard in the world has converted solely to air-cushioned vehicles, and those that operate them do so in specialized roles. Yet, there once was a time in the 1970s when the U.S. Coast Guard was seriously considering using these unique vehicles.

Notes

- Douglas R. Meier, U.S. COAST GUARD CUTTERS & SMALL BOATS: 1970 – 2024 (DOUGLAS MEIER, 2024). ↩︎

- Robert L. Scheina, U.S. Coast Guard Cutters and Craft, 1946-1990 (Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 193. Like other small boats in the U.S. Coast Guard, the first two numbers of the vessel’s numerical designator denote the craft’s length. ↩︎

- Scheina, 193. ↩︎

- “SR.N5,” in Wikipedia, March 18, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=SR.N5&oldid=1214310817. ↩︎

- “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted,” Coast Guard Aviation History, accessed May 1, 2024, https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/. ↩︎

- “Hovercraft,” in Wikipedia, April 20, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hovercraft&oldid=1219956361#United_States. ↩︎

- Scheina, 193. ↩︎

- “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted,” Coast Guard Aviation History, accessed May 1, 2024, https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/. ↩︎

- “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted,” Coast Guard Aviation History, accessed May 1, 2024, https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/. ↩︎

- “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted,” Coast Guard Aviation History, accessed May 1, 2024, https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/. ↩︎

- “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted,” Coast Guard Aviation History, accessed May 1, 2024, https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/. ↩︎

- Scheina, 193. ↩︎

- “Hovercraft,” in Wikipedia, April 20, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hovercraft&oldid=1219956361#United_States. ↩︎

- In the strictest sense, they’re amphibious vehicles. ↩︎

- The U.S. Navy term for the enlisted crewman who controls an LCAC is “Craft Master.” ↩︎

- “SR.N6,” in Wikipedia, March 18, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=SR.N6&oldid=1214310892. ↩︎

- Canadian Coast Guard Government of Canada, “How Hovercraft Work,” February 1, 2024, https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/icebreaking-deglacage/air-cushion-coussins-air-eng.html. ↩︎

Bibliography

Coast Guard Aviation History. “1970: Evaluation of Hovercraft Suitability for Coast Guard Use Conducted.” Accessed May 1, 2024. https://cgaviationhistory.org/1970-evaluation-of-hovercraft-suitability-for-coast-guard-use-conducted/.

Douglas R. Meier, U.S. COAST GUARD CUTTERS & SMALL BOATS: 1970 – 2024 (DOUGLAS MEIER, 2024).

Government of Canada, Canadian Coast Guard. “How Hovercraft Work,” February 1, 2024. https://www.ccg-gcc.gc.ca/icebreaking-deglacage/air-cushion-coussins-air-eng.html.

“Hovercraft.” In Wikipedia, April 20, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Hovercraft&oldid=1219956361#United_States.

Scheina, Robert L. U.S. Coast Guard Cutters and Craft, 1946-1990. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1990.

“SR.N5.” In Wikipedia, March 18, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=SR.N5&oldid=1214310817.

“SR.N6.” In Wikipedia, March 18, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=SR.N6&oldid=1214310892.