Designed during the Cold War to combat deep-diving, high-speed, nuclear submarines and high-performance surface warships, the Mark 48 is currently the U.S. Navy’s only heavyweight submarine-launched torpedo; replacing the older Mk. 14 and Mk. 37. This post will aim to examine the Mk. 48’s characteristics, development, and variants, as well as provide examples of usage.

Characteristics1

| Type | Heavyweight submarine-launched anti-surface ship & anti-submarine torpedo |

| Date of Design | ~1970 |

| Dimensions | Diameter: 21″ Length: 19″ Weight: 3,434 lbs. (mod 1); 3,695 lbs. (ADCAP); 3,520 lbs. (mod 6) |

| Warhead | 650 lbs. of PBXN-103 (plus any unused fuel) (equivalent to ~1,200 lbs. of TNT) |

| Range/Speed | >10,000 yds. at 28+ kts. (official figures) >35,000 yds. at 55+ kts. (speculated)2 |

| Depth | 2,500 ft. |

| Guidance | Wire-guidance, passive & active acoustic homing. Target acquisition at 4,000 yds. |

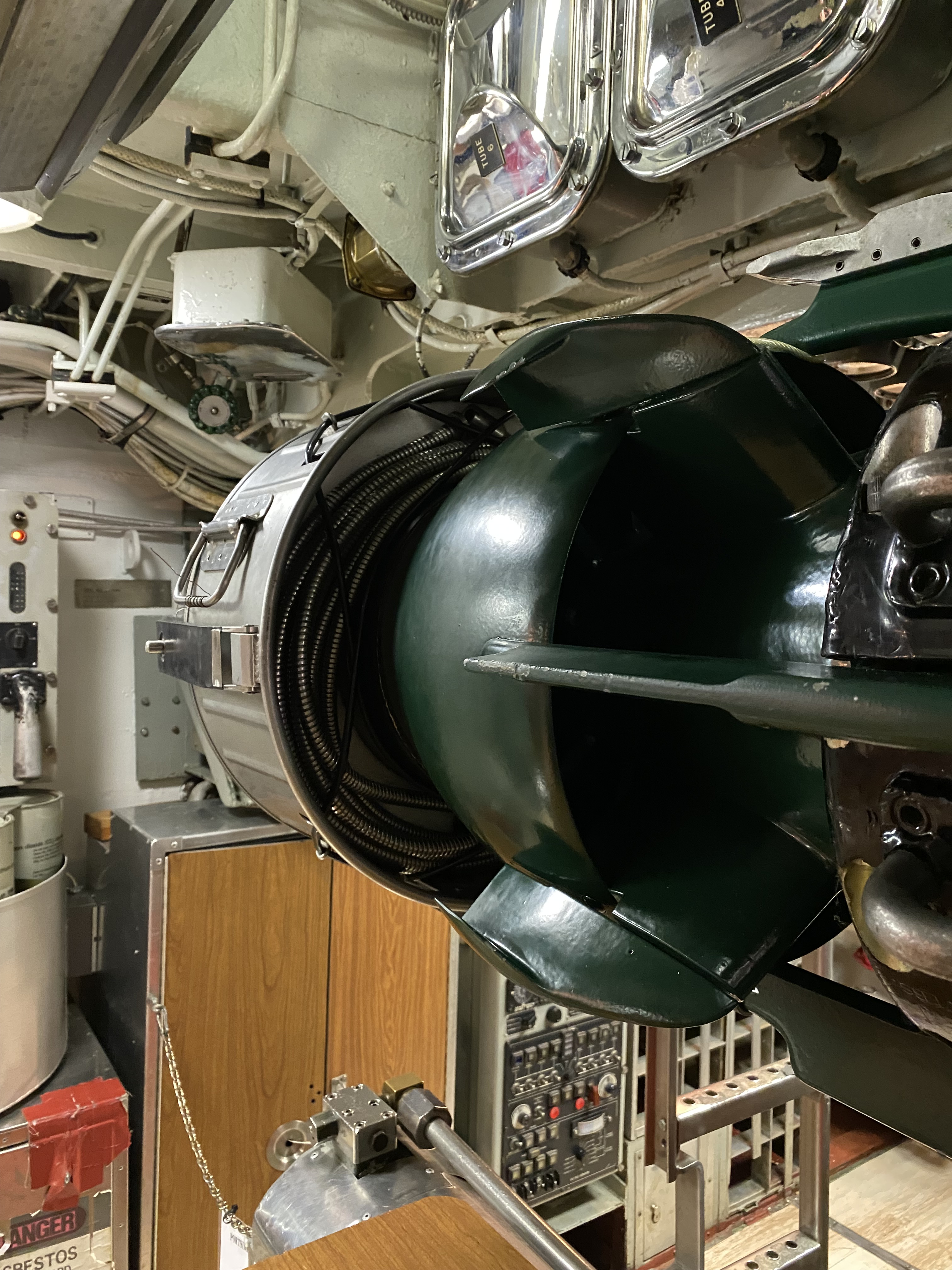

| Propulsion | Swashplate piston engine powering an axial-flow pump jet propulsor with contrarotating propellers. |

| Fuel | Otto fuel II monopropellant |

| Date in Service | Mod 1: ~1972 – 1973 Mod 2: Abandoned Mod 3: ~ 1973 Mod 4: 1980 Mod 5 ADCAP: 1988 Mod 6 ADCAP: 1997 Mod 7 CBASS: 2008 |

Development

The advent of nuclear propulsion to submarines in the 1950s (starting with USS Nautilus in 1954) signaled a new era of underwater capability, making submarines faster and possessing near-unlimited endurance. This spurred the U.S. Navy to study new Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) technologies to mitigate their advantages. The result was the Nobska Project in the summer of 1956, ordered by the new Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Arleigh Burke. Torpedo development in the 1950s and ’60s was concerned with the effectiveness of these weapons against deep-diving and fast nuclear-powered submarines. The Mk. 48 torpedo was one of the weapons that stemmed from this study.3

Feasibility studies for the Mk. 48, initially designated the EX-10, began in September 1957 with an Operational Requirement issued in November 1960. Entry into service was expected by 1967.4 Part of the Nobska Project involved research into homing torpedoes traveling at 45 knots against 30-knot nuclear-powered submarines. Two programs commenced, called RETORC (REsearch TORpedo Configuration). RETORC I eventually led to the Mk. 46 lightweight torpedo for surface ships, aircraft, and Anti-Submarine Rockets (ASROC). RETORC II produced the Mk. 48 heavyweight torpedo for submarines. In 1961, the RETORC II program settled on a pump-jet propulsor to minimize a torpedo’s self-noise. The program further stipulated the torpedo must have a range of 20,000 yards at 50 knots (Nobska’s goal originally called for a range of 35,000 yards at 45 knots), and a target acquisition range of 3,000 yards to allow for an acquisition cone of 20 times that of the Mk. 37.5

The U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) initially wanted turbine propulsion, but flow noise over the torpedo was found to be higher than engine noise, so a piston engine was selected. While the piston engine was less fuel-efficient, it maintained speed despite the higher pressures at greater depths, although it had less range. For fuel, BuOrd envisioned using 90% hydrogen peroxide and diesel oil, but this was switched to the monopropellant Otto fuel II in 1963. This is named after its inventor, Dr. Otto W. Reitlinger, and proved to be less temperamental than hydrogen peroxide. It was formally adopted for the Mk. 48 in February 1964.6

By the mid-1960s, the then-current Mk. 37 torpedo was deemed inadequate, with an effectiveness of roughly 10% against a submarine traveling faster than 20 knots and capable of diving deeper than 1,000 feet. Thus, the development of the Mk. 48 was considered urgent. Proposals called for a weapon with 40% effectiveness against submarines making greater than 35 knots and diving deeper than 2,500 feet. The primary issue was the torpedo’s propulsion to allow it to achieve the desired range, speed, depth, and target acquisition range. Being longer and heavier than the Mk. 37, it would possess quadruple the range (~35,000 yds. versus 9,000 yds.) and twice the speed (>50 knots).7 The Mk. 48 also needed to dive to 2,500 feet versus 1,000 feet and acquire its target at 4,000 feet versus 700 feet of the Mk. 37.

In 1965, BuOrd reported that its test vehicle had achieved the same noise level as the Mk. 37 while running at 54 knots. The silencing was achieved by the torpedo having a high transport speed of 55 knots, followed by a slower search speed of 40 knots. The high transport speed didn’t really matter if the weapon was wire-guided anyway. Once it got close to the target, the active sonar returns from the target were so strong that flow noise no longer mattered, and the weapon could speed up again to attack.8 Following a competition between qualified bidders, a contract was awarded to Westinghouse. Clevite (later known as Gould) was also awarded a contract to develop a different acoustic system for the torpedo.9 System tests were conducted in the fall of 1964 aboard USS Permit (SSN-594) in the Pacific, and the program was further accelerated with the Mk. 48 entering service in 1971.10

Originally, the Mk. 48 had a small 250 lb. HBX-3 warhead, but that was too small to sink large surface warships. Arguably, because of this, U.S. submarines continued to use the WWII-vintage Mk. 14 torpedoes, creating a mix of analog (Mk. 14) and digital (Mk. 48) torpedo loadouts. Naturally, this also required a mixture of both analog and digital fire control. To make the (then) new Los Angeles-class submarines all digital, the Mk. 48 was given a larger 650 lb. warhead to become a true dual-purpose torpedo; thereby negating the need for submarines to carry a mix of older and newer torpedoes.11 In fact, when designing the Los Angeles-class, a larger torpedo room had to be included to accommodate longer skids to store the larger Mk. 48 torpedo and its wire dispensers.12

Control

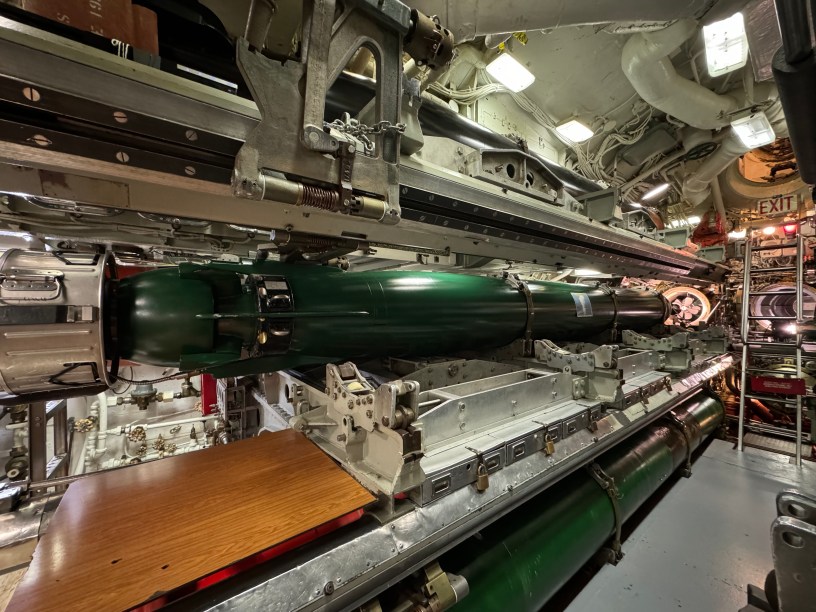

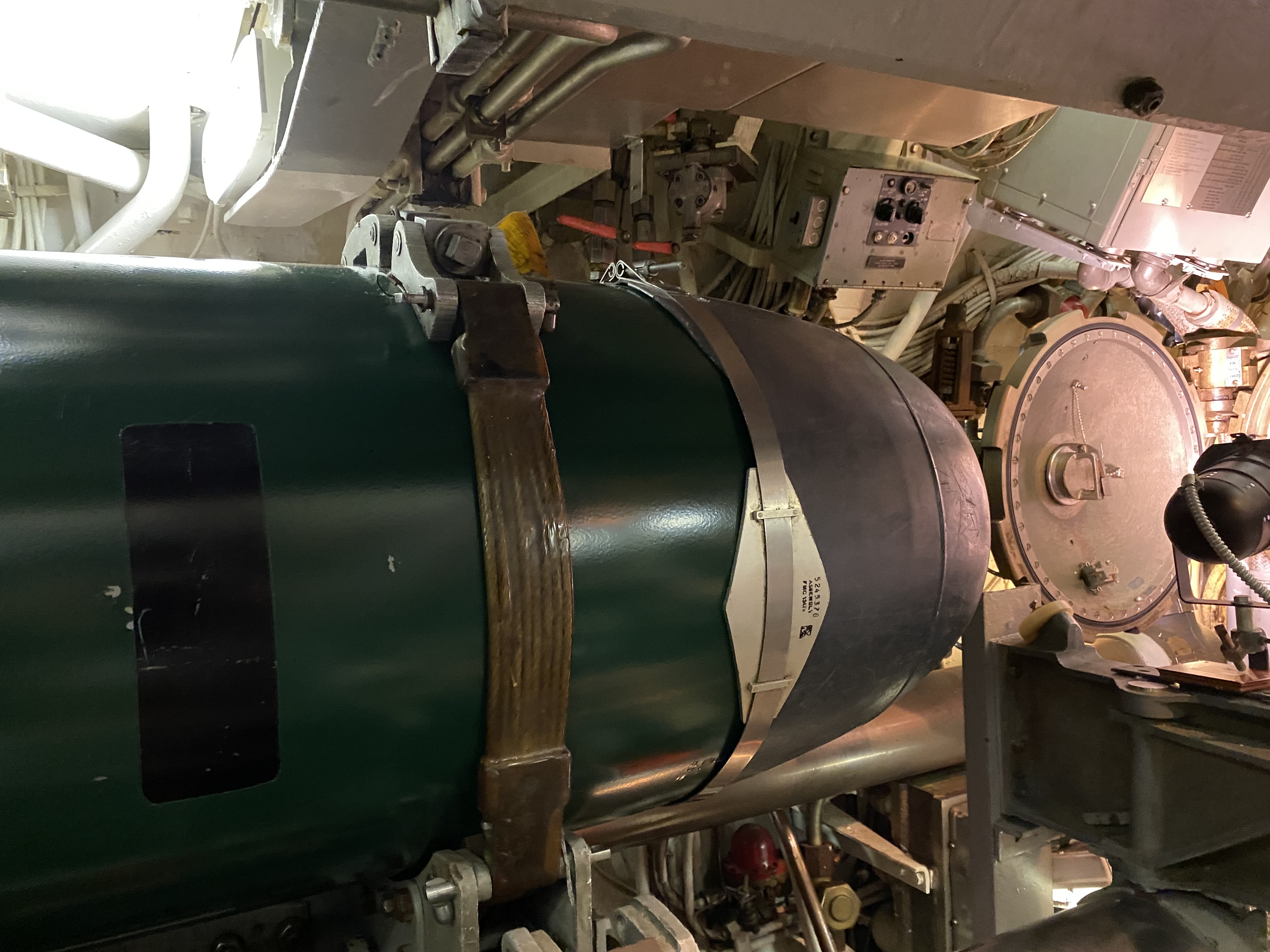

The Mk. 48 has wire mid-course guidance. When the torpedo is fired, the wire will spool out from a Tube Mounted Dispenser (TMD) can inside the torpedo tube (seen here attached to the rear of the torpedo), and an additional wire dispenser can be fitted over the pump jet propulsor on the rear of the torpedo, allowing for longer wire. This wire allows the firing submarine to guide the torpedo to its target using its more capable passive sonar.13 Should the torpedo miss its target, it has a reattack capability, and an updated attack profile can be transmitted to the weapon. While always intended as an anti-surface and anti-submarine weapon, the latter capability was emphasized during development.14 The wire guidance in the Mk. 48 is digital, unlike older Mk. 37 torpedoes, which use analog signals for wire guidance. This means more complex instructions can be sent to the torpedo, and signal loss over long distances is less of a problem. However, existing analog fire control systems on submarines, such as Mks. 101, 106, 112, and 113 needed separate Mk. 66 control consoles installed to transform the analog signals into digital ones.15 The wire guidance has the advantage of making the torpedo immune to most countermeasures and decoys as long as it’s being controlled by the submarine. Once the wire is cut (or if it breaks), then the torpedo’s own active or passive sonar will guide the weapon to the target based on its last instructions.

In the late 1960s, defense contractor Raytheon was developing a new integrated multipurpose sonar for submarines. This became the BQR-24. Replacing the Bearing Time Recorder (BTR) channel of the BQS-6 sonar with DIgital MUltibeam Steering (DIMUS), the BQR-24 was capable enough to provide short-range fire control data for the Mk. 48 torpedo. Using a technique known as Frequency-Line Integration Tracking (FLIT), the system analyzed Doppler measurements of narrowband frequencies to work out a target’s movement. With the own-ship and target ship shown on a situation display, the BQR-24’s computer could create prelaunch settings for the Mk. 48 much faster than a manual plot. While the BQR-24 was approved for service in 1974, and 11 sonars were purchased under the FY76 program, Raytheon ultimately lost to IBM, which provided the BQQ-5 that became the next integrated sonar suite. However, Raytheon still provided the sonar spheres. The BQQ-5 contract was awarded on 13 December 1969.16

In 1983, the Secretary of the Navy’s Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) raised concerns over the efficacy of U.S. torpedoes. The committee suggested using small nuclear torpedoes, which could overcome most countermeasures against conventional torpedoes, to supplement existing conventional torpedoes. It was also suggested that insertable technology could convert conventional weapons into low-yield nuclear weapons on submarines. However, there was immediate opposition from the U.S. submarine community, ostensibly due to the concern that open discussion on the weapons would reveal classified information. Interestingly, Norman Polmar writes that this concern was, in reality, a reaction to fear that U.S. submarines were vulnerable to Soviet ASW weapons. While there was broad support from others on the topic, senior submarine officers eventually abandoned any further discussion of both nuclear and conventional weapons to augment the Mk. 48. Over time, upgrades to the Mk. 48 have focused on improving the torpedo’s performance against high-performance Soviet submarines; the negation of mutual interference from launching a two-torpedo salvo; firing the torpedo while under ice where acoustic reverberations create problems; and the torpedo’s performance against quiet diesel-electric submarines.17

Variants

| Mod | Description |

|---|---|

| Mod 0 | Derived from the Research Torpedo Configuration II (RETORC II) program developed by Penn State University and Westinghouse.18 This variant used a turbine and was an ASW-only weapon.19 |

| Mods 1 & 2 | By 1967, an anti-surface capability was needed. These mods resulted from a competition between Clevite/Gould and Westinghouse. Clevite/Gould developed the Mod 1, which included a swashplate-piston engine powered by Otto fuel and a different acoustic system. Westinghouse further refined the Mod 0, which became the Mod 2. It featured a Sunstrand turbine. A pilot production contract was awarded in October 1970, followed by a test between Mods 1 and 2 in June 1971. Ultimately, in July 1971, Gould was awarded a full-scale production contract for the Mod 1, and the Mod 2 was abandoned. One of the reasons was that the piston engine was more efficient when running deep, although the Mod 2 with the turbine was quieter. Mod 1s began entering the fleet in 1972.20 |

| Mod 3 | Added a TELCOM (Telecommunications) two-way (as opposed to one-way) wire communication between the torpedo and the firing submarine. This allows the torpedo to transmit its sonar, depth, course, and speed data back to the submarine’s fire control system. Acoustic Homing Improvement modifications also improved its performance against low-doppler and surface targets. Mod 3 began appearing in 1973.21 |

In the 1970s, the Soviet Alfa-class submarine entered service. These submarines featured a titanium hull, allowing them to dive to a test depth of 1,300 feet.22 Their small size and powerful reactor also allowed them to achieve speeds of up to 40 knots. Concerned about this new threat, the Chief of Naval Operations issued a new operational requirement in 1975, which led to the following two upgrades to the Mk. 48.23

| Mod 4 | Further improved the TELCOM guidance and added a fire-and-forget mode, which was useful if the torpedo’s noise blanked out the submarine’s passive sonar. Additionally, the torpedo’s operating envelope was increased, allowing it to travel faster and dive deeper. Existing torpedoes were upgraded with kits to the Mod 4 standard, and full production began in 1980.24 |

| Mod 5 ADCAP | Stemmed from a November 1978 Navy request for an Advanced Capabilities (ADCAP) version.25 In August 1979, Hughes was tasked with developing a new guidance system to allow the torpedo to acquire faster and deeper diving Soviet submarines. While the existing swashplate piston engine was retained, increased fuel flow allowed the weapon to achieve a speed of approximately 63 knots. Other improvements aimed at creating a stronger shell that could carry more fuel, have reduced self-noise, more sensitive passive sonar, more powerful active sonar, and be electronically steered to reduce the need for the torpedo to maneuver. The new guidance system and computer use electronically steered sonar beams, allowing the seeker head to see in a nearly 180-degree hemisphere ahead of the weapon and largely eliminating the need for the torpedo to snake about along its course to search for a target, like in previous mods. This new mod involved new digital electronic components and an inertial guidance system, which replaced the older gyro system. These changes freed up a significant amount of internal space and allowed for an increased fuel capacity and about 50% greater range (up to 50,000 yards). The introduction of microprocessors and integrated circuitry allowed the control functions to be moved to the nose of the torpedo, and the 10-mile guidance wire spool to be moved aft of the larger fuel tank. (With the additional 10 miles in the wire dispenser in the tube, the submarine could clear the launch area while still guiding the weapon.) The Mod 5 ADCAP entered service in 1988, with full production beginning in 1990. The last ADCAP was delivered in 1996.26 |

| Mod 6 MODS ADCAP | Added a Guidance and Control (G&C) modification and upgraded the Torpedo Propulsion Unit (TPU). The former enhanced the acoustic receiver, updated the technology of the torpedo’s guidance and control systems, increased the memory, and improved the processing speed. These changes included the Torpedo Downloader System (TDS), which meant that deployed submarines could update the weapon’s software to the newest version. This was the first mod to include that feature. The TPU upgrade significantly reduced the torpedo’s noise signature, making it substantially quieter (one of the main criticisms of previous mods). Mod 6 reached Initial Operating Capability (IOC) in 1997. The Mk. 48 Block IV upgrade began in 1999. At that time, the Navy had about 1,046 Mod 6 torpedoes that replaced an equal number of Mod 5s.27 |

| Mod 7 CBASS | Resulted from a Joint Development Program between the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy. This modification added a Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System (CBASS), which added advanced counter-countermeasure capabilities, such as frequency agility and optimal frequency selection of a target, allowing the torpedo to recognize and ignore countermeasures. It also optimized the torpedo against targets in both deep and littoral waters (<180m) using a fully digital wideband sonar system. It achieved IOC in 2006.28 |

Further upgrades include the Stealth Torpedo Enhancement Program (STEP), which will occur in two phases. Phase 1 improves the guidance and eliminates sonar footprints, and Phase 2 improves the stealth and propulsion of the weapon, including an upgraded warhead.29 Details of the CBASS and STEP upgrades are still classified, but it’s believed that the newest mod of the Mk. 48 can actually “swim” out of the torpedo tube under its own power, which is significantly quieter than being fired out of the tube by a slug of seawater.

USS Blueback

A Mk. 48 torpedo is on display in the torpedo room of USS Blueback (SS-581); however, the documentation on the boat indicates that it’s a Mk. 48 mod 1. So it’s technically not a mod 5 ADCAP version. According to former crewman (and volunteer tour guide) Rick Neault, Blueback only carried Mk. 48 torpedoes when he served aboard her from 1988 to 1989. Exactly what mods she carried is currently unknown.

Users30

- United States

- Australia

- Taiwan

- Brazil

- Canada

- Israel

- Netherlands

- Turkey

The Mk. 48 is exported to a number of countries and warshots (torpedoes with live warheads) have been fired during sinking exercises (SINKEX), including by foreign navies that use the weapon.

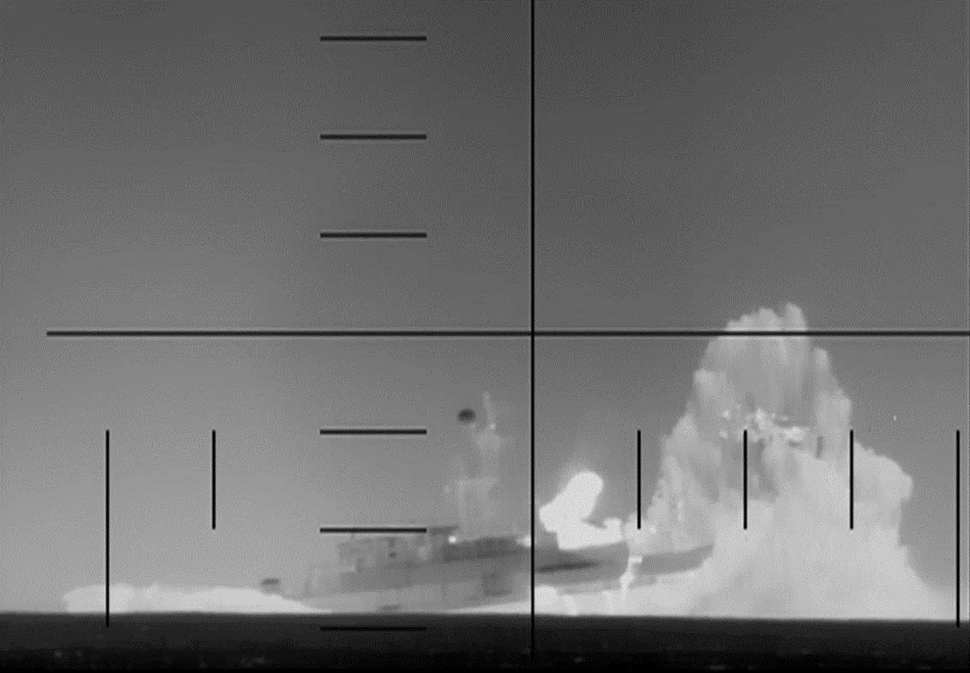

The Mk. 48 is designed to travel underneath the target and detonate, creating a massive void in the water and breaking the keel. With the keel broken, a ship can’t support its own weight, and it will buckle. The following images and videos clearly demonstrate the destructive power of this torpedo.

The first live Mk. 48 Mod 5 ADCAP was fired on 23 July 1988 by USS Norfolk (SSN-714), which sank the Forrest Sherman-class destroyer USS Jonas Ingram (DD-938) during an exercise.31

First Combat Use of the Mk. 48 Torpedo

On 3 March 2026, the Improved Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine USS Charlotte (SSN-766) became the first submarine (to my knowledge) to fire Mk. 48 torpedoes in combat when she sank the Iranian Moudge-class frigate IRIS Dena just south of Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean. Charlotte fired two torpedoes, but the first one missed, and the second one detonated beneath the stern of IRIS Dena. Like other footage of test shots during SINKEXs, the detonation lifted the vessel’s stern out of the water, buckled it, and it sank stern-first.32

This event is also significant because it’s also the first time in over 80 years that a U.S. Navy submarine has fired a torpedo in anger. The last time was on 14 August 1945, when USS Torsk sank several ships in the Sea of Japan just before the end of World War II.

Conclusion

The Mk. 48, being the (current) sole submarine-launched torpedo, stands in marked contrast to Soviet/Russian weapons. By the end of the Cold War, the U.S. had three weapons (Mk. 48 torpedoes, Harpoon anti-ship missiles, and Tomahawk missiles) that could be fired from a submarine’s 533mm tubes. In contrast, the Soviets had developed submarines with both 533mm and 650mm that could launch a greater variety of tactical weapons.33

The continued upgrades to the Mk. 48 torpedo since its introduction in the early 1970s, have kept the torpedo viable as a potent submarine-launched weapon. Of course, the current versions of the Mk. 48 are far removed from the original mods, and most of the improvements have been on the inside in terms of software, but the Mk. 48 stands as a testament to the reliability of the physical technology and its adaptability to modern computing technology. Having been in service now for over 50 years, and having only been fired in combat once, the live torpedoes fired during sinking exercises continue to demonstrate the weapon’s effectiveness. With no word of any replacement, the Mk. 48 torpedoes will continue to see service as the U.S. Navy’s only heavyweight submarine-launched torpedo for the foreseeable future.

Notes

- Norman Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons: Every Gun, Missile, Mine and Torpedo Used by the US Navy from 1883 to the Present Day, Repr (Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 269; “Post-World War II Torpedoes of the United States of America – NavWeaps,” accessed April 7, 2024, http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WTUS_PostWWII.php. Hereafter referred to as Navweaps. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 269. The actual range and speed are classified. Speculated figures for the Mk. 48 mod 0 are based on the designed characteristics of a torpedo with twice the range, speed, and diving depth of the previous Mk. 37. ↩︎

- Norman Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945: An Illustrated Design History, Revised edition. Printed case edition (Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2023), 110 – 111. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 120. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 113. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 112 – 113. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 120 – 121. According to Friedman, as a rule of thumb, a homing torpedo needs to be about 50% faster than its target to have an effective chance of catching it. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 113. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 120. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 113. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 163. ↩︎

- Reportedly, the early mods of the Mk. 48 used copper wire, but it’s believed that current mods use fiber optic cables. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 120. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 113. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 73. ↩︎

- Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore, Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1. ed (Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005), 293 – 294. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Naval Weapons, 120. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Polmar & Moore, 140 – 146. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps; Tom Clancy, Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside a Nuclear Warship, 2nd ed. (New York, NY: Berkley Books, 2002), 96-98. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Navweaps. ↩︎

- Wikipedia; Navweaps. To my knowledge, the Mk. 48 is exported to other countries but only manufactured in the United States. On one of my tours on USS Blueback, a visitor adamantly claimed that Japan manufactures Mk. 48 torpedoes. I pointed out that this doesn’t make any sense since Japanese laws (given its pacifist constitution post WWII) prohibit the export of weapons. (Although this may be slightly changing as they begin exporting certain fighter jets, exports will be very limited.) Additionally, the U.S. already has a strong industrial base for domestic weapons development and manufacture, and Japan manufactures its own weapons for its Self Defense Forces with some exceptions. Japanese torpedoes are their own design. I can only conjecture that some electronic components for the Mk. 48 may be manufactured in Japan, but they certainly don’t manufacture the torpedo itself. ↩︎

- “MK-48 Torpedo,” accessed April 7, 2024, https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ship/weaps/mk-48.htm. ↩︎

- James LaPorta and Eleanor Watson, “Torpedo That Struck Iranian Warship Was Fired by USS Charlotte, U.S. Officials Say,” CBS News, March 5, 2026, https://www.cbsnews.com/live-updates/us-iran-war-spreads-azerbaijan-israel-strikes-tehran-lebanon/. ↩︎

- Polmar & Moore, 305. While the later SSN-21 (Seawolf-class) submarines have larger 670mm tubes, no larger U.S. weapons have been developed for those tubes, and they continue to use conventional submarine-launched weapons. ↩︎

Bibliography

Friedman, Norman. US Naval Weapons: Every Gun, Missile, Mine and Torpedo Used by the US Navy from 1883 to the Present Day. Repr. Annapolis, Md: Naval Institute Press, 1988.

Friedman, Norman. U.S. Submarines since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Revised edition. Printed case edition. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2023.

LaPorta, James, and Eleanor Watson. “Torpedo That Struck Iranian Warship Was Fired by USS Charlotte, U.S. Officials Say.” CBS News, March 5, 2026. https://www.cbsnews.com/live-updates/us-iran-war-spreads-azerbaijan-israel-strikes-tehran-lebanon/.

“MK-48 Torpedo.” Accessed April 7, 2024. https://man.fas.org/dod-101/sys/ship/weaps/mk-48.htm.

Polmar, Norman, and Kenneth J. Moore. Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. 1. ed. Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005.

“Post-World War II Torpedoes of the United States of America – NavWeaps.” Accessed April 7, 2024. http://www.navweaps.com/Weapons/WTUS_PostWWII.php.

Clancy, Tom. Submarine: A Guided Tour Inside a Nuclear Warship. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Berkley Books, 2002.