Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the presenter’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of either the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), the United States Navy, or the United States Government. While strong efforts are made to ensure accuracy, all information is subject to change without notice. All personal statements, opinions, omissions, and errors are the commentators’ own.

More information about the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), as well as USS Blueback, can be found on the museum’s website at omsi.edu. OMSI is a non-profit organization that receives support from various sources, including generous donations from people like you.

Not every tour guide on Blueback is a submarine veteran. In fact, a number of the guides came from the surface fleet; having served on destroyers and cruisers. In this post, we have one of those sailors and a more general (non-submarine) related sea story from a Vietnam veteran.

Featured Tour Guide – Dave Pierce – BT2, U.S. Navy

Our featured (volunteer) tour guide in this post is Dave Pierce. Dave served in the U.S. Navy as a Boiler Technician 2nd class aboard USS Hamner (DD-718) from September 1971 to December 1974. Following his time in the Navy, Dave managed a lumber yard for Copeland Lumber before his retirement. He’s been volunteering at OMSI since 2006 in various capacities, including being part of Blueback‘s Maintenance Crew.

With nearly 20 years of experience (and counting) as an OMSI volunteer, Dave brings a unique experience as a tour guide; having not served on submarines. With his characteristic raspy voice, he’s always keeping his tours fun and representing the surface sailors aboard Blueback.

Transcript

Tim:

Hello, welcome back to Down Periscope, Up Periscope. My name is Tim. I’m your host. And today we have another special guest for the podcast, but not a submarine sailor. We are here with one of our volunteer tour guides, Dave Pierce. And I’m just gonna ask him a little bit about what his time in the Navy was like because Dave has an interesting background in that he is a surface sailor, much like a couple of other of us are. So welcome, Dave.

Dave:

Hello there, Tim. Thanks for having me.

Tim:

Thank you. So Dave, you’re a destroyer man, essentially.

Dave:

Absolutely. Tin Can sailor is what they refer to us as.

Tim:

That’s right. And when did you join the Navy and why did you want to be in the Navy?

Dave:

Well, I joined the Navy in January of 1971. The reason I went in the Navy is because prior to that, there was a draft lottery for anybody that was 18 or older. And my birthday came up number three and they were taking the first 120 numbers into the Army. So I decided rather go in the Navy and that’s how that started.

Tim:

All right. Interesting. What rating? What job did you want to do when you joined the Navy?

Dave:

Well, when I first enlisted, I was going to be a nuclear sub sailor. So I went through a boot camp and then went back to Great Lakes, Illinois, and to their first school. And at that time they did a little more, you know, physical, check your eyes better, check your teeth and all that, a lot better. And I found out that I couldn’t be on a submarine with my eyes uncorrected the way they were. So I was offered either being a boiler technician or going on an aircraft carrier. And I said, “I’ll be a boiler technician.”

Tim:

I see. All right. And eventually, you found yourself aboard the Hamner, a Gearing-class destroyer.

Dave:

Yes. USS Hamner, DD-718, built in 1945.1 And it was almost 30 years old when I got on it. So we already experienced a lot of seamanship.

Tim:

Did you enjoy your job as a BT?

Dave:

Well, at the beginning, not so much. It wasn’t until I made rate. It was dirty and it’s hot down there in the fire rooms. And so it wasn’t ideal for me. But once I started putting on the petty officer’s badges, then it became a lot more fun. I didn’t have to do a lot of the stuff I had to do as a junior enlisted and I enjoyed it.

Tim:

Very good. Now, for some listeners out there and even Navy veterans, boiler technicians no longer exist as a rating.

Dave:

That’s correct. They don’t have that.

Tim:

So what exactly does a boiler technician do?

Dave:

Well, back in those days, all the ships were driven by steam except for an aircraft carrier and the submarines. And so steam was made by a boiler and you took water and heated it up basically and made steam out of it. And the steam was high-pressure steam, 600 pounds per square inch. And when it came right out of the boiler as you got going on that ship and then they turned it into superheated steam, meaning they reheated the steam to 850 degrees. And so if you ever had a leak on one of the valves and you walked by it, you weren’t paying attention, you’d cut yourself with that.

Tim:

Oh, wow. And obviously, you were there to make sure the boiler didn’t explode.

Dave:

Well, true. That’s true. And it took – even on a typical watch, it took four people per boiler. There would be a checkman, which would control the flow of the water going into the boiler. There was a messenger. There was a top watch who controlled the air going into the boiler and ran the whole thing. And then there was a burner man and he would be firing the burners. There was four burners on the saturated side. There was three burners on the super-heated side.

Tim:

So eventually, as you were on the Hamner, you got deployed to Vietnam.

Dave:

Yep.

Tim:

What were your initial feelings and thoughts about that?

Dave:

Well, that’s a tough one. We knew that we were going to go there, but as a rule, Navy ships weren’t seeing much action. They would do a little gunfire support. However, once we got over there, it turned a complete different direction. We would be going in at night and drawing fire from the beach, from the North Vietnamese, and then letting the spotter planes see where the brights were coming [from]. We called them brights. Then they would radio the carrier that was sitting off the other side of the horizon to fire in some jets to land. So we did that. We went in every night, came out every night, and we would fire and they would fire back at us.

Of all the ships that were over there, there was about 30 that were Gearing-class destroyers. We were the only ones that didn’t take a direct hit. We did have one that went through the ensign, but that was as close as they came. We had shrapnel all over the place.

Tim:

Do you have any idea what was firing at you?

Dave:

Not really. I don’t. Something like three-inch shells. If you looked at the pictures of the guns, it looked like old Civil War cannons. That’s what they were using, but I’m not sure.

Tim:

And I think you told me one time you were going up and down the coast doing counter-battery fire for these reasons.

Dave:

Yeah. Well, we actually shot over 10,000 rounds of counter-battery, about the whole nine months we were over there. The first thing that we did was we had to shadow a North Korean trawler. And we followed that thing around where we were right actually a mile away from it, running side by side with it. And I wasn’t quite sure what that was all about. We weren’t at General Quarters or anything. And then one time they called us to General Quarters because the thing had fired a shell at us. So we knew that it wasn’t just a trawler. And of course one of our 5″/38s took care of it. That was the end of our patrol.

Tim:

And Vietnam has quite an expansive coastline. So whereabouts were you off the coast?

Dave:

God, that would be hard to say, we were, we went into Da Nang a couple of times. And we even went as far north as Hanoi, you know, and that is because we were in Haiphong Harbor, which is Hanoi’s port, rescuing a pilot there one time. So I really don’t know how much of that coast we covered, but the ones that we were, they were shooting back. [laughing]

Tim:

And you mentioned one time you were patrolling with a Coast Guard cutter, U.S. Coast Guard cutter Chase. Now, unlike your ship, you know, those cutters were fairly new at the time and, you know, they were a combined gas and diesel engine.2 So you mentioned one time that thing was leaving you in the dust for a while.

Dave:

It absolutely was. You could hear it. It sounded like a jet, you know, taking off and we could do almost 40 miles an hour. We could do 38 knots. And that thing left us in the dust many times.

Tim:

And did you mention one time that there was a scare, like some MiGs or something were flying over?

Dave:

Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah. The USS Higbee. We were at General Quarters. They were probably three-quarters to a mile away from us, off to the left. And we were both going in the same direction. And we were at General Quarters, but that didn’t necessarily mean I couldn’t go up and have a smoke. And so I was up having a smoke and I looked up, and saw this bright flash come out of the sky. And it was a MiG and it, I can’t remember if it really dropped bombs or if it fired something at the Higbee, but it, whatever it was, it blew their after gun mount off. I mean, really, right off. And come to find out later, luckily there had been a fire in the magazine and they had flooded it.3 And so there was no explosion, but they did have to replace the gun mount. Well then, after that MiG circled around, I thought, ‘well, it’s going to come and get us,’ you know. But before it could, I saw this streak of light come through the sky, and it was an anti-aircraft missile. I can’t remember what type it was. Came from the USS Chicago from 65 miles away.4 That’s what I heard later. So blew that thing into smithereens.

Tim:

Yeah, I see. What it sounds like, I’m not too familiar with Vietnam War history, but that’s the Battle of Dong Hoi. Isn’t that where Higbee was bombed?

Dave:

Yeah, I think so. And the names I wasn’t really familiar with, too. It’s hard to say. You know, you’re out either in gunfire support or you’re drawing fire or you’re, you know, on search and rescue or plane guard operations. And so you’re all in the same territory, but I really couldn’t tell you specific names besides Da Nang and Hanoi.

Tim:

Well, very good. It’s interesting. So eventually, how long were you in the Navy for?

Dave:

I was in the Navy almost four years, a month and a half shy of four years. Active duty. You’re always signed up for six years, you know, two years inactive.

Tim:

And so after you got out, then what happened to you?

Dave:

Well, prior to me getting out, about three months before I got out, I met this girl. And I liked this girl, so I wasn’t going to get out. I was going to extend my service and make E-6.5 And then that changed everything. So when I got out, I came up to Portland, Oregon from San Francisco and lived here, and went to work at a lumber yard six months after my unemployment ran out. [laughing] And then come to find out the ship itself had transferred from San Francisco to Portland. And so I saw a lot of the guys that I thought I was leaving behind on a regular basis.

Tim:

So yeah, you managed a lumber yard for a number of years, and eventually you found yourself at OMSI.

Dave:

I sure did. Back in 2006, I don’t know who I was talking to, said they had a big Star Wars display down here at OMSI. And I should volunteer and you get to see all this stuff. And it sounded like a good thing. So I did that. I did guest services for six months until the exhibit moved on to someplace else. And then after that, I needed something to do. So I decided I’d become part of the submarine maintenance crew. And Bob Walters, who goes to our church, was the one that kind of turned me onto that. And at first, it worked out really good. It was from four o’clock in the afternoon to eight o’clock at night on Mondays. And that wasn’t hard for me to do. The problem was that the recession was in the middle of all that and the hours changed and everything. So they went from noon to four o’clock and I couldn’t do that. And so I ended up going to the PEPCO building where they built the displays and did the same routine, helped them there because they were there from four to eight, or I could be there from four to eight, I should say. But they went to the noon to four routine too. So I took about a six-year sabbatical from OMSI and they came back after I retired to become a submarine tour guide. And here I am now 10 years later.

Tim:

And you’re shooting for 5,000 hours of volunteering.

Dave:

Five thousand hours or 20 years. And 20 years.

Tim:

If you can kind of condense it down, what’s something that you really enjoy about being a tour guide on Blueback here?

Dave:

Oh, the people! Meeting the people. You know, 99.9% of them are excellent. They’re all engaged. They like it. And the people is really the visitors or customers. That keeps me going. Keep in mind that the crew that we have here is about the best we’ve had since I’ve been here too, though; I’ll be honest with you now. You know, in 10 years we have a peak and this is it. Good crew. Glad you’re here.

Tim:

Yeah. Yes, we do have a really good crew. All right. Well, that’s all the questions I’ve got for you, Dave. But thank you very much for taking your time to answer some questions.

Dave:

Thanks for asking me.

End of Transcript

The 1972 Easter Offensive

To provide some more context for what was happening during the Vietnam War around the time Dave was there, we need to look at the 1972 Easter Offensive, the Battle of Dong Hoi, and the drawdown of U.S. forces.

The Nixon Administration’s policy of “Vietnamization” beginning in 1969 gradually saw the drawdown of U.S. forces in Vietnam and the turning over of combat operations to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). With the U.S. forces withdrawing and the disastrous ARVN Operation Lam Son 719 into Laos in February and March 1971, the North Vietnamese seized the opportunity. Despite constant U.S. air attacks on the Ho Chi Minh trail, and with additional supplies from the Soviet Union and Communist China being funneled into North Vietnam via Haiphong Harbor, the North Vietnamese began moving thousands of men, hundreds of tanks, and tons of supplies into position for another offensive by early 1972.6 The so-called Easter Offensive, which began on 30 March 1972, was the first major North Vietnamese offensive since the Tet Offensive of 1968. Despite the monsoon weather, U.S. Navy surface ships began conducting gunfire missions along the coast, and the two aircraft carriers on Yankee Station in the Gulf of Tonkin, USS Hancock (CVA-19) and USS Coral Sea (CVA-43) responded to the North Vietnamese thrust against the provincial capital of Quang Tri with airstrikes. Within a week, they were joined by USS Kitty Hawk (CVA-63) and USS Constellation (CVA-64).7

USS Hancock and USS Constellation were later shifted to Dixie Station in the South China Sea to forestall the enemy advance on the provincial capitals of An Loc and Kontum. These were supported by B-52 “Arc Light” strikes flying from Thailand and Guam. The North Vietnamese eventually captured Quang Tri, but their assault on Hue was halted. By mid-April, the carrier USS Midway (CVA-41) arrived, followed by USS Saratoga (CV-60) in mid-May. This concentration of six aircraft carriers was the largest since World War II and not equaled until Desert Storm in 1991.8

USS Hamner’s April to May 1972 Deployment

The destroyer USS Hamner was deployed to Vietnam multiple times throughout the conflict. Hamner‘s last deployment to Vietnam was from April to May 1972 for operations around the Haiphong Do Son Peninsula in the Gulf of Tonkin.9 During that deployment, the North Vietnamese had just commenced the Easter Offensive. This was the time Dave was aboard her, and it was her last deployment before heading to the Reserve Fleet. Of course, as Dave mentioned, they ranged up and down the coast of North Vietnam from Hanoi and Haiphong Harbor, and south to at least Da Nang which is just south of the Demilitarized Zone on the 17th parallel in South Vietnam.

On 14 April, the Joint Chiefs of Staff authorized the Seventh Fleet to strike targets further north. The Charles F. Adams-class guided-missile destroyer USS Joseph Strauss (DDG-16), along with the Gearing-class destroyers USS Higbee (DD-806), and USS Bausell (DD-845) fired on two SAM sites near Vinh. Around this time, nine destroyers under Task Unit 77.1 were conducting gunfire missions north of the DMZ and were joined on occasion by the Seventh Fleet flagship, the guided-missile cruiser USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5). Altogether, they fired 11,679 rounds at numerous SAM (Surface-to-Air Missile) and AAA (Anti-Aircraft Artillery) sites, radar installations, coastal artillery positions, bridges, road junctions, and other targets.10

Regarding the operations in Haiphong Harbor, Commander Mike Cuseo, the Executive Officer (XO) of USS Bausell recalls that his ship, along with the destroyers USS Buchanan (DDG-14), USS Hamner, and USS George K. MacKenzie (DD-836), rendezvoused with USS Oklahoma City on the night of 15 April 1972 about 40 miles east of Haiphong Harbor. As they approached the harbor, they drove through hundreds of fishing sampans and spotted a long line of mostly Soviet merchant ships leaving the harbor; no doubt these had resupplied munitions to Communist forces, but they couldn’t be engaged. Once they were 8 miles from the shore and a few miles from the Do Son peninsula, they commenced firing at hundreds of pre-designated targets, such as AAA and SAM batteries. These batteries were firing at strike aircraft launching from the aircraft carriers USS Coral Sea, USS Kitty Hawk, and USS Constellation on Yankee Station. Along with B-52s and other Air Force aircraft, these planes were hitting targets in the area.11

Cuseo described the scene as follows:

The closer we got to Haiphong, the more intense the hostile fire became. An amazing number of water geysers were erupting all around us – plus thousands of black puffs of air bursts all around and above our battle group. It was literally a page out of a WWII sea battle. I was mesmerized. I was broken out of my revelry by the Captain yelling “X.O.!! Get off the wing and get here under shelter! Better yet, get back to secondary con in case the bridge gets a direct hit. We can’t both be disabled.”12

At about 2 miles from the coast, the ships executed a “nine turn” which was a 90-degree turn to the left to unmask all of the guns. Cuseo recalls seeing a fighter aircraft get hit by a SAM overhead and the pilot eject. The ejection seat splashed into the water near USS Bausell and the pilot parachuted down aft of them. As Bausell swung out of formation to pick up the pilot, they were ordered to return, and USS Hamner, directly behind them, picked up the pilot instead. Hamner would receive an “attaboy” several days later from President Nixon, and the Commanding Officer was decorated with a Bronze Star with a Combat “V” for his actions.13 Chief Hull Maintenance Technician (HTC) Maurice “Morrie” D. Karst, a crewman on board Hamner, recalls that the rescued aviator was Commander David Lee Moss, whose A-7 Corsair II was shot down over Haiphong Harbor.14 With their magazines exhausted, the destroyers returned to Yankee Station to rearm, thus ending the first gunfire mission undertaken that far north in Vietnam.15

The Battle of Dong Hoi

On 19 April, USS Oklahoma City, along with the destroyers USS Sterett (DLG-31),

USS Lloyd Thomas (DD-674), and USS Higbee (DD-806) were firing on coastal targets around the area of Dong Hoi.16 Oklahoma City, trailed by Higbee and Thomas, were operating about 5 miles offshore and 2,000 yards apart. Thomas was controlling Sterett‘s helo, which was overhead, providing spotting for the shore bombardment. Sterett was maneuvering at 5 knots and holding position 12 miles from the target area with her bow pointed toward the shore to keep her missile launcher unmasked to provide cover from air attack.17

Around 1700, radar detected three air contacts inbound. Two MiG-17s from the 923rd Fighter Regiment of the Vietnamese People’s Air Force (VPAF), each armed with two 550-pound bombs made attacks on Oklahoma City and Higbee.18

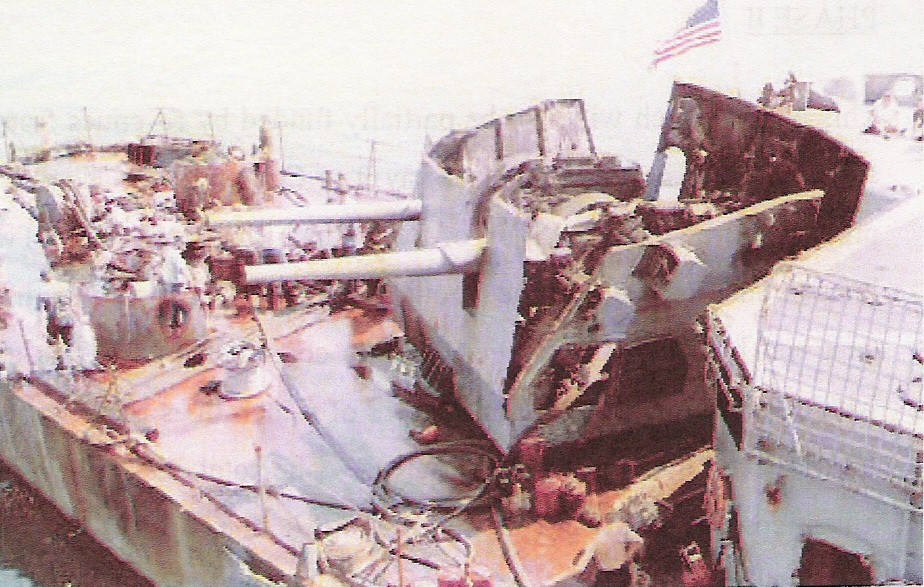

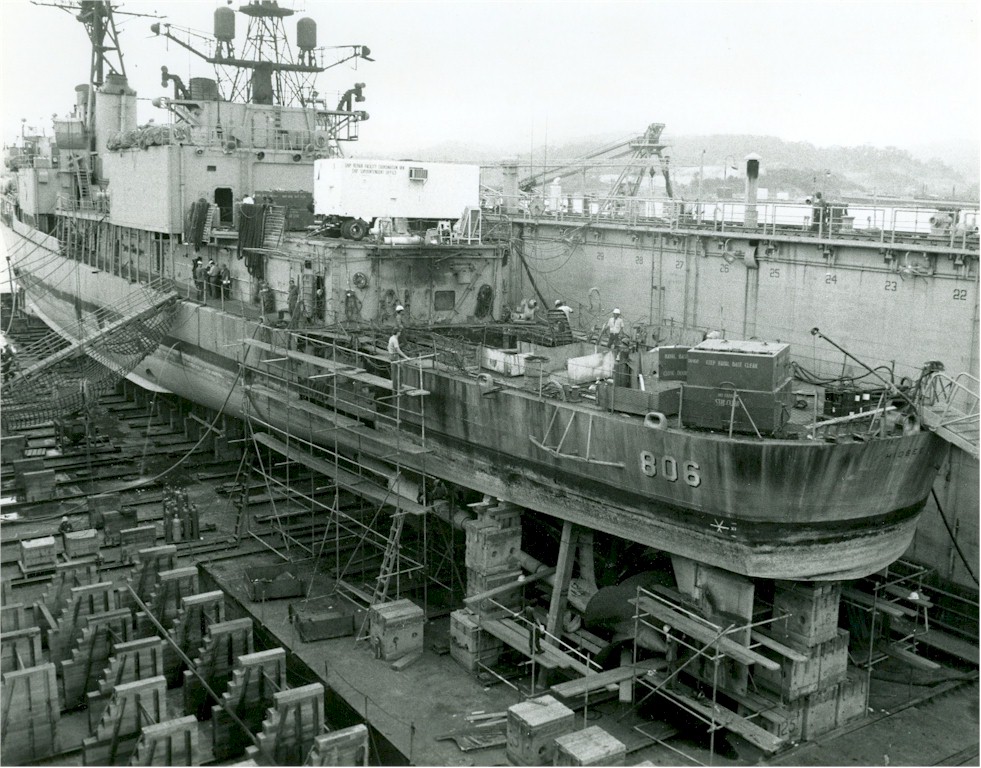

The first MiG overshot Oklahoma City but circled around to make another attack with both bombs, which missed, causing only slight damage to her rudder. The second MiG attacked Higbee and scored a direct hit on her after 5″ gun mount. Luckily, the gun had suffered a hangfire with a jammed shell in the barrel, so the gun crew had already evacuated the mount before the attack. The bomb hit destroyed the gun mount and wounded four sailors.19

Witnesses to the attack mention that one MiG was shot down by a Terrier missile fired from Sterett, and another was possibly shot down, as well. On the other hand, Vietnamese accounts note that both jets landed safely, but one overshot the runway and was stopped by the arrestor barrier with minimal damage.20 From Sterett‘s point of view, according to an after-action report, at the start of the engagement, they held positive radar contact on two aircraft flying at an altitude of 3,000 feet above the hills of the coastline over Dong Hoi. One of the aircraft approached the formation, flying at about 50 feet when Sterett fired a salvo of two missiles, scoring a hit with the second. After Higbee was hit, Sterett detected two additional hostile aircraft over Dong Hoi and fired another salvo as the ships departed the area. The two aircraft turned and fled between the mountains, but there were reports that one of the aircraft was intercepted by one of the missiles outside of visual range; bringing Sterett‘s count to two MiGs successfully shot down that day.21

As Oklahoma City, Higbee, and Thomas retired, Sterett stayed behind to provide cover, but a confused radar picture developed with various false targets being reported. One surface contact was detected at about ten miles away and an air contact was observed separating from the contact which closed Sterett at 500 yards per second. Sterett fired on the air contact with her Terrier missiles, achieving a successful intercept at 7,400 yards. This air contact was evaluated as a probable SS-N-2 Styx anti-ship missile launched from the surface contact.23

The ships moved further offshore and Sterett detected two high-speed surface contacts which turned out to be North Vietnamese P-6 torpedo boats that were shadowing the force on a parallel course. With the sun going down, Sterett engaged and sank the two torpedo boats with her 5″ guns. However, the radar picture was described as very confusing, and Vietnamese accounts don’t confirm any torpedo boats sunk on this day.24

On the same day that Higbee was bombed, the destroyers Buchanan, George K. Mackenzie, and Hamner shelled bridges near the city of Vinh, about 100 miles north of Dong Hoi. During their shelling, two motor patrol boats (believed to be Shanghai-class) approached the ships from behind an island. MacKenzie fired on the boats and drove them off. A few minutes later, Buchanan received fire from a 122mm shore battery. One shelled airburst above the ship, killing one sailor and wounding six others. On 21 April, 33 U.S. Navy carrier aircraft conducted airstrikes on the Khe Gat airfield near Dong Hoi where the MiGs that struck Higbee took off from. One MiG was destroyed and another was damaged on the ground. As a result of these Vietnamese anti-ship attacks, the U.S. Navy ceased close-in daylight operations off North Vietnam. Only nighttime shelling was conducted from hereon.25

Discrepancies

USS Hamner’s Position on 19 April

Dave mentioned in his interview that he witnessed Higbee being bombed, however, I have found no source which indicates that Hamner was operating with Higbee, Lloyd Thomas, and Oklahoma City off Dong Hoi on 19 April. Samuel Cox’s narrative from the Naval History and Heritage Command mentions that Hamner was shelling bridges 100 miles north near the city of Vinh on that same day. On the other hand, the official history for the destroyer USS Buchanan mentions that she, along with Hamner, and MacKenzie actually shelled these bridges two days earlier, on 17 April 1972.26 In this case, two official Navy histories provided two conflicting dates regarding USS Hamner‘s position.

Dave also mentioned to me that other sailors were on deck smoking with him when he witnessed the missile streak across the sky, so there are others to corroborate his story. Of course, he got a number of facts incorrect. He mentions the missile was fired from the cruiser USS Chicago (CG-11), not the Sterett, and from 65 miles away. The range of a RIM-2 Terrier was only about 17 miles.

Now, I don’t mean to imply that Dave is lying or exaggerating, since I do believe he witnessed something, but my policy is to always corrobate oral histories with official or reputable published sources. I’m in no way trying to discredit anybody’s experiences, but as I’ve said before and I’ll say again, memory does funny things over time.

It could be that the official histories from the Naval History and Heritage Command website are incorrect, and Hamner was actually present at the Battle of Dong Hoi. After all, even official histories are known to be wrong at times, and the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships gives absolutely nothing of USS Hamner‘s operational history after 1967.

No doubt Hamner and Higbee probably operated together at some point during the war at this time, and it’s no doubt that Dave was aware of the attack on Higbee. However, it’s possible that Dave falsely remembered witnessing an event he heard through hearsay regarding Higbee. It’s also possible that he saw an aircraft that he mistakenly identified as a MiG, when it may have been a friendly aircraft. Remember that these destroyers were providing counterbattery fire on targets ashore and vectoring in carrier aircraft to hit targets all throughout this time, as well. Recall that Dave mentioned that Hamner got lucky and never took a direct hit out of all the Gearing-class destroyers that were there. It’s possible that they were operating with Higbee, spotted an aircraft overhead, and saw Higbee take a hit, not from an aircraft, but from a shore battery. Then he witnessed a SAM shoot down the aircraft.

In the end, we don’t really know.

Research Follow Up

After locating USS Hamner‘s deck log for April 1972 from the National Archives catalog, I’ve been able to ascertain some of the events that Dave mentioned. For example, Hamner and Higbee did indeed operate together on at least one occasion from 9 – 12 April as part of a Task Unit. On 12 April, Hamner pulled into Da Nang harbor and moored alongside USS Buchanan. She got underway again about five hours later.27

On 15 April, Hamner‘s deck log notes that at 0004, she was operating off Haiphong Harbor as part of Task Unit 77.1.2, composed of USS Benjamin Stoddert (DDG-22), USS Richard B. Anderson (DD-786), USS John R. Craig (DD-885), and USS Gurke (DD-783). By 1550, she had rendezvoused with USS Buchanan, USS Bausell, USS Everett F. Larson (DD-830), and USS Oklahoma City. Buchanan was in the lead of the column, followed by Bausell, Larson, Hamner, and Oklahoma City. The column was on a base course of 028, speed 20 knots. The column maneuvered around, and at 2229, Hamner went to General Quarters, set material condition zebra throughout the ship, and commenced firing at 2305. At 0007 the next day, they ceased firing and secured from General Quarters, having expended 201 rounds of 5″/38 shells (200 AAC and 1 WP). At 1059, Hamner continued to conduct naval gunfire support, and at 1107, the log notes that they spotted a parachute off the starboard bow. They maneuvered around and at 1115 recovered CDR D.L. Moss, commanding officer of VA-94. It notes that he had only sustained some bruises for injuries. Hamner ceased firing at 1119.28 This information from the deck log correlates with what happened that day when the ships went into Haiphong Harbor.

Regarding Hamner‘s position on 19 April, the day of the Battle of Dong Hoi, where Higbee was bombed, Hamner was operating with Buchanan, Stoddert, and Mackenzie just off the coast south of Vinh and conducting naval gunfire support. Around 1432, Hamner loaded ammo from USS Pryo (AE-24) and completed replenishment around 1520. She continued to conduct gunfire support throughout the day and rendezvoused the following day with USS Guadalupe (AO-32) to take on fuel in the same area.29 In contrast, the deck log for Lloyd Thomas, operating with Oklahoma City and Higbee, gives coordinates that are directly off Dong Hoi, which is about 90 miles south of where Hamner was operating that day.30

The information from the deck logs of both Hamner and Lloyd Thomas confirms that the former wasn’t present at the Battle of Dong Hoi, and given the distance between the two ships, there’s no way Dave witnessed Higbee being bombed by the MiGs. The question remains about what exactly Dave witnessed. As I previously conjectured, it’s possible Dave saw Higbee take fire earlier, possibly when they were operating together and conducting gunfire missions between 9 and 12 April. Any earlier operations between Hamner and Higbee are difficult to ascertain since Hamner‘s deck log for March 1972 isn’t available, and Higbee‘s March 1972 deck log makes no mention of the two ships operating together on the gun line, so I can’t corroborate any information.

Some other interesting notes from Hamner‘s April 1972 deck log include rescuing a downed Air Force pilot, 1st Lieutenant Richard Lee Abbot, on 2 April. The next day, while conducting naval gunfire support, enemy guns fired back, and about 30 rounds of what’s believed to be 105mm shells splashed 300 – 500 yards astern of the ship. Hamner returned the favor with 118 five-inch shells. (This happened on several other occasions, as well.) On 5 April, just as Hamner had finished refueling from USS Navasota (AO-106), she did an emergency breakaway to avoid two sampans that crossed in front of the formation. On 14 April, CDR E.A. Hamilton relieved CDR R.N. Blackington as the commanding officer. On 17 April, 8 minutes after midnight, Hamner fired on a “high speed surface contact.” The log doesn’t mention if they sank the contact. A similar event occurred on 20 April around 2133.31 Hamner‘s deck logs prior to April and after August for 1972 aren’t available. So what she did for the remaining time that Dave says they were in Vietnam is unknown. Dave mentioned that they first shadowed a North Korean trawler, but I somewhat doubt that was one of those two surface contacts she engaged on 17 and 20 April, respectively.32

Hamner would eventually be pulled off the gun line back to Subic Bay, Philippines, and return to Vietnam for more duty. In late July, she made a port call in Hong Kong and then returned to Vietnam. She returned to Subic Bay multiple times and then went back to Vietnam for further duty. In August, she spent most of her time on Yankee Station with the carriers USS Saratoga (CV-60) and USS Oriskany (CV-34) doing plane guard duty.

Other Thoughts

It’s also worth noting that, being a Boiler Tech, Dave’s normal watch station wasn’t in an area of the ship that would normally allow you to get a clear view of the big picture. It was in the boiler room, not on the bridge or the Combat Information Center. Furthermore, his description of the guns firing at them as being like Civil War cannons is a bit of a stretch, in my opinion. I’m willing to bet that the guns that were firing at them were not antiques or museum pieces. The North Vietnamese military, from what I’ve read, wasn’t the Vietcong guerrillas with the black pajamas and conical straw hats trudging around the rice paddies of the Mekong Delta in South Vietnam. In contrast, they were well-trained and well-equipped from various Communist sources. While they didn’t possess all the high-tech gear that the U.S. military had, they were still a professional force to be reckoned with.

Whatever the case, you’ll always find discrepancies in these anecdotes. That’s why these are called sea stories. As we say, “This was no shit!”

BT Punches & Sailor Words

Newbie sailors will often be sent looking for various items around the ship. For example, Dave mentioned that every so often, a new sailor would come down to the boiler room with an empty bucket in hand to ask the boiler technicians for a “bucket of steam.” Another item could be a “BT punch” which is an item about as big as a person’s hand and is used for punching holes in things. Upon asking for this, the new sailor gets slugged hard by the boiler tech. I asked Dave if any sailors ever asked him for the “BT punch” and if he ever gave them one. He replied that he’d been asked many times, but since he’s actually a nice guy, he wasn’t big into hazing, so he never dished out any BT punches.

However, he also told me that he’s only hit another sailor once. He was trying to teach this new Seaman how to clean the boiler and the kid just wasn’t getting it. So the kid did the smart thing and started mouthing off. Dave, who had enough of this kid’s attitude, and having run out of patience, proceeded to smack him upside the head. (Remember kids, this was the ’70s and things weren’t kinder or gentler back then.) A word of advice, don’t get cute with a Petty Officer because they’re trained in the FAFO school of discipline. F Around and Find Out.

Conclusion

So that’s a sea story from BT2 Dave Pierce, a tin can sailor, Vietnam veteran, and veteran volunteer at OMSI. His stories remind us that destroyers are the backbone of the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet. I always enjoy talking with Dave because he lacks the snobby pretentiousness that you sometimes find with submariners (indicative of someone who’s let their status go to their heads). Dave’s a very honest and straight-shooting kind of guy and gives a great tour of Blueback.

I encourage anyone to come down for a tour of USS Blueback if you’re in the Portland area, you just might get Dave as your tour guide. Regardless of whether it’s your first time or you’ve taken multiple tours of the boat before, we all give different tours and have different stories to tell.

Footnotes

- Laid down on 25 April 1945, launched on 24 November 1945, commissioned on 12 July 1946. ↩︎

- Correction: CODOG (Combined Diesel Or Gas) powerplant. ↩︎

- The cause was actually a misfired shell that was stuck in the barrel. So the gun mount was evacuated. ↩︎

- He mistakenly says USS Chicago when it was USS Sterett. ↩︎

- Petty Officer 1st Class. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. At the end of 1969, there were some 475,200 U.S. troops in Vietnam; however, by the end of 1971, that number had fallen to around 10,000 ground combat troops, with the remainder being advisors and support personnel. By mid-1972, even the number of support personnel had fallen to less than 30,000. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- “USS HAMNER (DD-718) Deployments & History,” accessed January 30, 2025, https://www.hullnumber.com/commands1.php?cm=DD-718. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- “Commander Mike Cuseo’s: An Amazing Day,” accessed January 29, 2025, https://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/misc/cww/2012/amazing_day.htm. ↩︎

- “Commander Mike Cuseo’s: An Amazing Day.” ↩︎

- “Commander Mike Cuseo’s: An Amazing Day.” ↩︎

- “The ‘Real’ Navy,” accessed January 29, 2025, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~handcosd/history/MHS/morrie/real-navy.html. ↩︎

- “Commander Mike Cuseo’s: An Amazing Day.” ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Charles “Chuck” A. Bond, “Dong Hoi Action — Sterett Association,” September 7, 2020, https://www.sterett.net/the-sterett-ships/dlg-cg-31/dong-hoi-action/. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Charles “Chuck” A. Bond, “Dong Hoi Action — Sterett Association,” September 7, 2020, https://www.sterett.net/the-sterett-ships/dlg-cg-31/dong-hoi-action/. ↩︎

- Not to be confused with the famous Vietnamese ace Nguyen Van Bay. ↩︎

- Charles “Chuck” A. Bond, “Dong Hoi Action — Sterett Association,” September 7, 2020, https://www.sterett.net/the-sterett-ships/dlg-cg-31/dong-hoi-action/. There’s a lot of debate as to whether this was an antiship missile, but it’s difficult to verify with official sources. If it did in fact occur, it would be the first instance of a U.S. ship being attacked with an anti-ship missile. Other articles on Tony DiGulian’s website Navweaps.com, specifically the one written by Stuart Slade and another written by Larry Rouse and William Berry point to a confused radar environment and the possibility that it was actually a MiG-17P. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- Samuel Cox, “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1” (Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf. ↩︎

- “Buchanan III (DDG-14),” accessed January 30, 2025, http://public2.nhhcaws.local/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/buchanan-iii–ddg-14-.html. ↩︎

- “USS Hamner DD-718 Deck Log Book,” U.S. Navy, April 1972, 538939744, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- “USS Hamner DD-718 Deck Log Book,” U.S. Navy, April 1972, 538939744, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- “USS Hamner DD-718 Deck Log Book,” U.S. Navy, April 1972, 538939744, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- “USS Lloyd Thomas DD-764 Deck Log Book,” U.S. Navy, April 1972, 235096771, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- “USS Hamner DD-718 Deck Log Book,” U.S. Navy, April 1972, 538939744, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- A ship’s deck log isn’t exactly a work of Shakespearean literature. It just gives bare facts. Date, time, course, speed, and the general activity of the vessel. At this time, the ship was going this way, going this fast, and doing this. The amount of detail in the log somewhat depends on who wrote it and what they put in it, but it’s usually pretty bare bones. ↩︎

Bibliography

Bond, Charles “Chuck” A. “Dong Hoi Action — Sterett Association,” September 7, 2020. https://www.sterett.net/the-sterett-ships/dlg-cg-31/dong-hoi-action/.

“Buchanan III (DDG-14).” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/buchanan-iii–ddg-14-.html.

Cox, Samuel. “H-070-1: The Vietnam War Easter Offensive, Part 1.” Naval History and Heritage Command, April 27, 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/about-us/leadership/hgram_pdfs/H-Gram_070.pdf.

“Commander Mike Cuseo’s: An Amazing Day.” Accessed January 29, 2025. https://www.emmitsburg.net/archive_list/articles/misc/cww/2012/amazing_day.htm.

“The ‘Real’ Navy.” Accessed January 29, 2025. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~handcosd/history/MHS/morrie/real-navy.html.

“USS Hamner DD-718 Deck Log Book.” U.S. Navy, April 1972. 538939744. U.S. National Archives.

“USS HAMNER (DD-718) Deployments & History.” Accessed January 30, 2025. https://www.hullnumber.com/commands1.php?cm=DD-718.

“USS Lloyd Thomas DD-764 Deck Log Book.” U.S. Navy, April 1972. 235096771. U.S. National Archives.