The Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) is located in Portland, Oregon on the east bank of the Willamette River. In addition to the featured exhibit(s), the museum also features the decommissioned U.S. Navy submarine, USS Blueback (SS-581) on permanent display. Daily 45-minute guided tours are offered several times an hour, and for those looking for a more in-depth experience, 3-hour technical tours are offered several Sundays each month.

The accompanying video below is a highly detailed version of my regular tour, and this blog post will be an even more detailed breakdown of the submarine, its systems, and life aboard submarines, in general. No doubt more information will be added to this post as I learn more about the submarine and its systems.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Author’s Note & Disclaimer

- Video

- Barbel-class

- Exterior

- Interior

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

Author’s Note & Disclaimer

I should establish that I am approaching this museum ship with a definite bias since I have experience as a tour guide on this submarine. Every museum has a particular interpretation of its exhibits, and OMSI is no different. As a museum, OMSI has displayed Blueback in a certain way and wants the interior to be kept as close to the original as when she was in service.

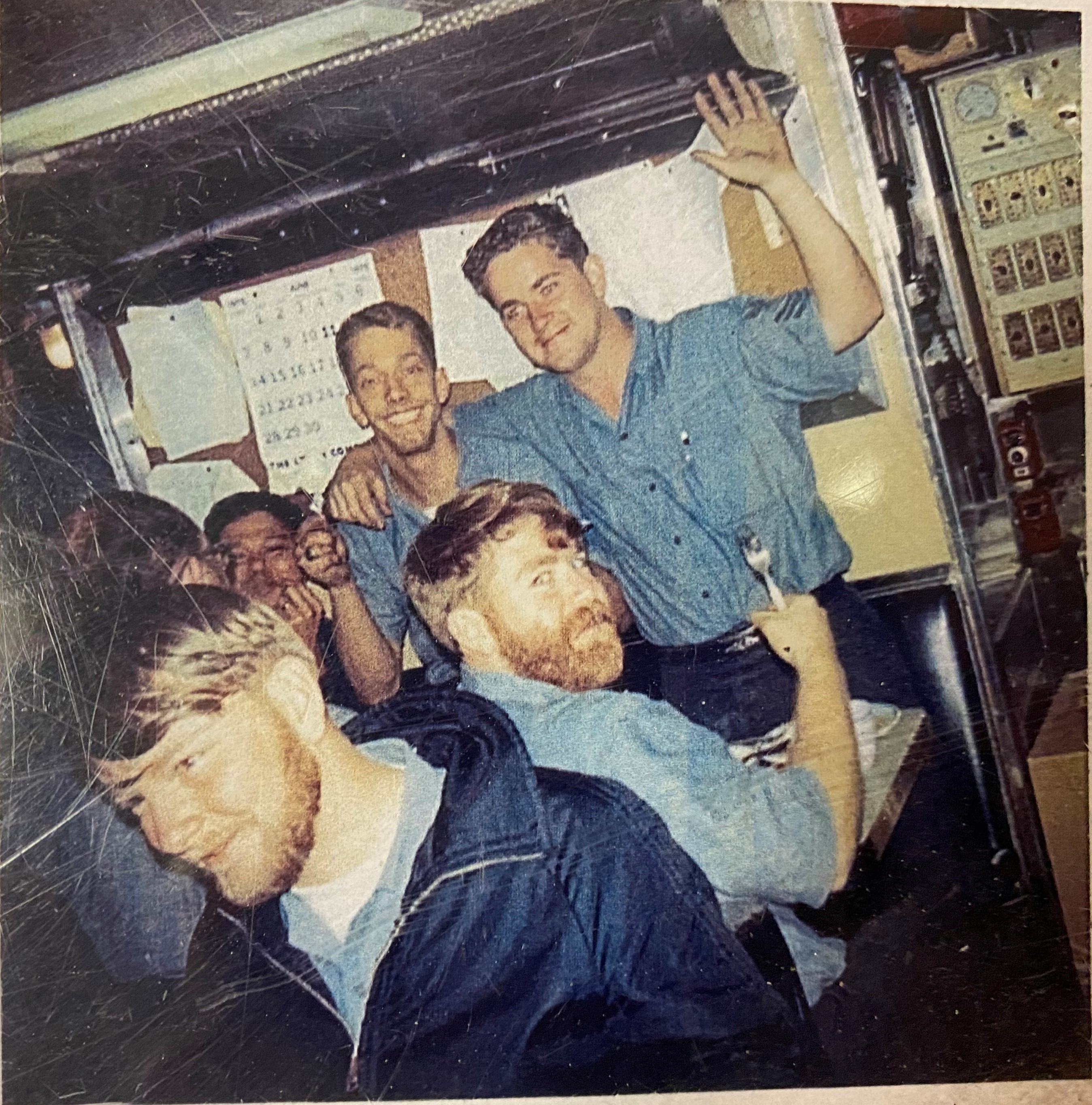

All of the tour guides on Blueback operate off a basic set of information about the boat and the experiences of the sailors who served on it. Many of the tour guides are Navy veterans and qualified submariners. Others, such as me, are not. As of 2025, there are only two (volunteer) tour guides on the staff who served on the three boats of this class, so their understanding of this submarine is far beyond any of ours. Contrary to what some people think, naval/sea/submarine experience is not required for this job (or to be a volunteer), and it really has little bearing on the quality of the tour. No, we DO NOT memorize a script. You will hear different stories from different tour guides because we each make the tour our own. The technical information about the boat will be (mostly) the same and it only constitutes a small fraction of the tour. Most of what we talk about is the life of submarine sailors. In fact, there is so much to talk about that you could easily take the tour with five different tour guides, and you will get five different tours. Our job is to provide “interpretive tours” to the visitors. My interpretation is by no means the final say, and I will try to make it clear when I am incorporating information from other tour guides or sources in this article.

Some people have a problem with guided tours because they cannot go at their own pace, but the interior of the boat is not conducive to self-guided tours. Furthermore, the tour guides are trained to keep the tours to around 45 minutes, so you will spend no more than about 5 minutes in each area, with additional time allotted for moving from room to room. Simply put, there is no way for the tour guide to put all the information and stories about this submarine into a single tour. One thing a tour guide does not want to do is to go so slow and let the incoming tours back up behind them. So we cannot just stay in one place and talk for an hour about whatever; we need to keep the tour moving because another tour is coming up right behind us.

For those desiring a longer and more detailed tour, I recommend buying tickets for a Technical Tour.

A word on historical research: One of the biggest frustrations historians encounter when doing research is determining what sources to use and their reliability. I have tried to source information from official published sources, as well as the submarine itself. However, I have also had to rely on my fellow tour guides for additional information that may not be in published sources. The problem with any kind of hearsay or oral history (which is essentially what a guided tour is) is that there is always the danger of misattribution. Given that only two guides served on the Barbel-class boats (and only one of them on Blueback herself), I usually take what I hear with a grain of salt. Just because they say it happened on their submarine does not mean it applies to this submarine. Memories change over time; some of the recollections of these tour guides are decades old, and some stories based on personal experiences may only apply to that particular person. The reality is that our memories are extremely fallible and prone to influence from other sources despite our best efforts. Hence, I am very wary of believing everything I hear from an oral history unless I can verify the details from a published source. In other cases, the oral history is all I have to go on.

Disclaimer: The personal statements, opinions, omissions, and errors expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of either the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), the United States Navy, or the United States Government. While strong efforts are made to ensure accuracy, all information is subject to change without notice.

Video

I have only found a handful of videos on YouTube with decent camera work and audio that feature an entire tour. So I decided to make my own. I shot it in segments and added some notes in post-production. What is shown in the nearly 2-hour-long video is an extremely detailed version of what would be my own 45-minute tour. Bear in mind that this is a general tour and not a 3-hour-long technical tour because I am not qualified to give those (only qualified submariners give those tours). I also included a lot of information in this video that I would not include on my normal tour because I am not limited by a 45-minute long time constraint here. Additionally, this video is not meant as a substitute for an actual tour. I encourage anyone interested to book a tour of the submarine and visit the museum if you happen to be in Portland, Oregon. There is nothing quite like seeing the real thing up close and personal. You will get to see, touch, hear, and smell the real submarine, and you will hear different stories from our different tour guides. Each of us gives a unique tour!

What I discuss in this video is down below; however, the blog post contains even more detailed information about the submarine, its systems, and naval history that would not be on any tour.

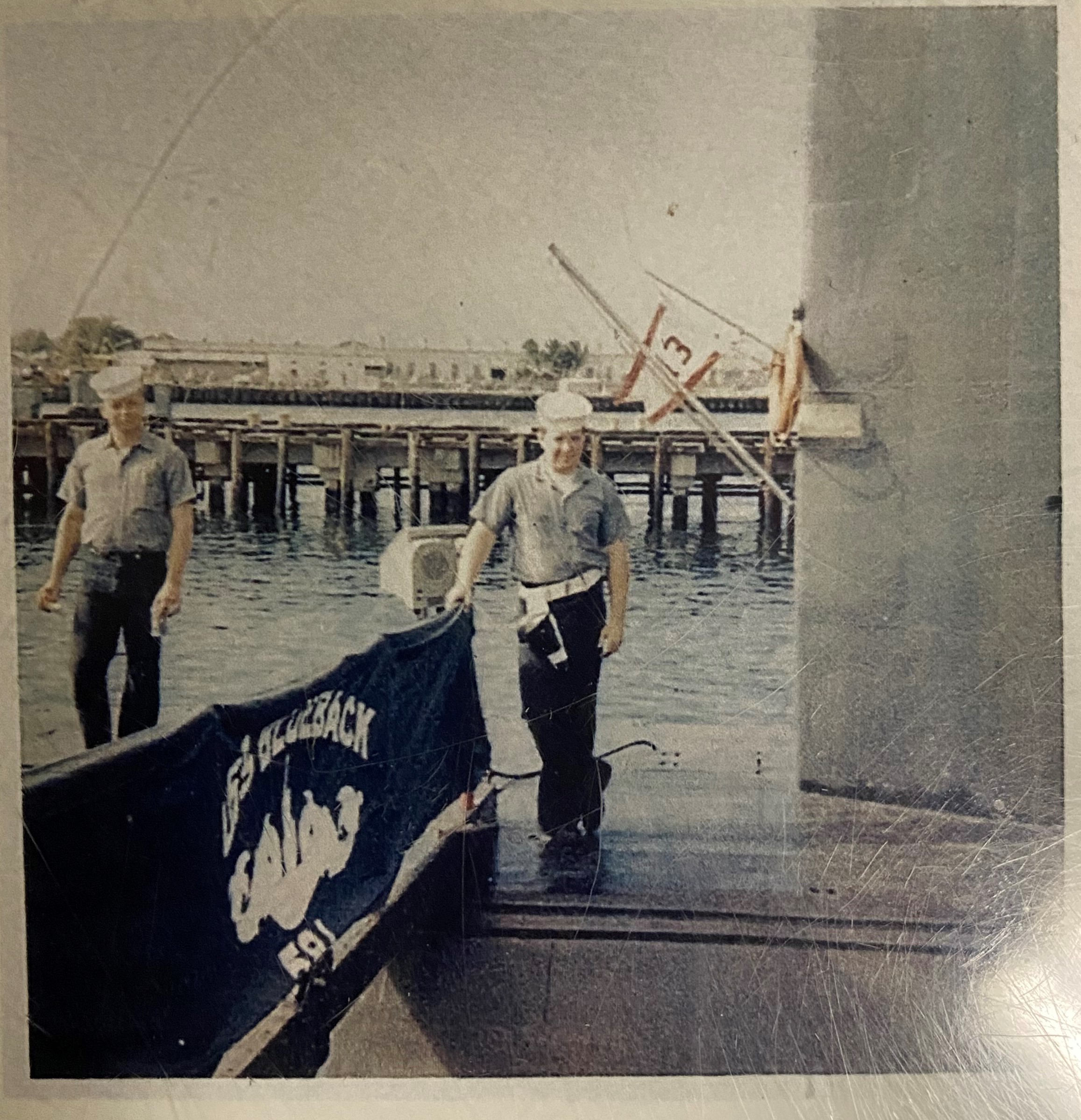

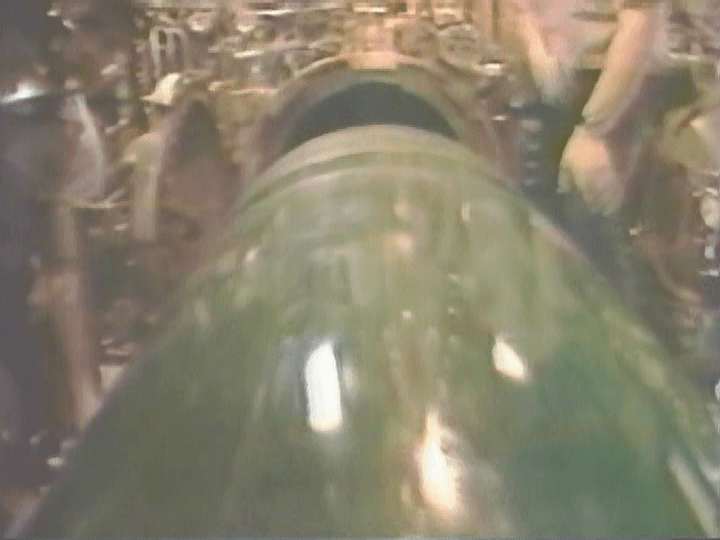

Barbel-class

USS Blueback (SS-581) is one of three Barbel-class submarines constructed; the other two are USS Barbel (SS-580) and USS Bonefish (SS-582).1 These were the first production attack submarines in the U.S. Navy with a teardrop-shaped hull (AKA body of revolution, or Albacore hull, after the experimental USS Albacore (AGSS-569)). Blueback was built by Ingalls Shipbuilding Corporation in Pascagoula, Mississippi for a cost of $21 million.2 Her keel was laid down on 15 April 1957, she was launched on 16 May 1959, and commissioned on 15 October 1959. After 31 years of service, she was decommissioned on 1 October 1990 becoming the last diesel-electric attack submarine in the U.S. Navy. When she was decommissioned, she left the Navy with an entirely nuclear-powered submarine fleet.3 I will withhold any further discussion of her service history for an article on the Barbel-class itself.

Following her decommissioning, she was laid up in the Pacific Reserve Fleet in Bremerton, Washington. Through a community effort led by Oregon Senator Mark O. Hatfield, OMSI acquired the submarine, upon which she was towed up the Willamette River and permanently moored at the dock in February 1994. She was opened up to public tours on 15 May of that year.4

Exterior

Approximately 90% of the Blueback (both exterior and interior) is original; however, all classified materials and equipment were removed by the Navy before turning her over to the museum. Additionally, roughly 62% of the submarine’s systems are still operational…and the tour guides are not going to tell you which ones are because they do not want you touching any of the buttons, switches, knobs, or valves. Some of them do set off alarms, and you could damage the equipment.

While the Navy technically still owns the boat it would never be put back into service for several reasons. First, a submarine’s hull is only good for about 30 years (give or take) before it needs to be decommissioned due to metal fatigue. Second, the museum cut a big hole in the side of the hull for the visitor’s entrance, which compromised the hull’s structural integrity. Third, the screw was unshipped and placed next to the museum building as a monument. Fourth, the electric motor was damaged in a fire at the end of her service life and would require replacement. Fifth, the flood ports (and other hull penetrations) on the bottom of the hull were plated over because they were found to be clogged with river silt during her last drydock period. Sixth, the torpedo tubes were welded shut.5

Sail

The large rectangular structure sticking out of the hull with the “581” on it is known as the sail. The number 581 means that she was the 581st planned submarine commissioned by the U.S. Navy. So “SS-581” means “Ship Submersible number 581.” This number will never be used again and the newer Virginia-class attack submarines currently under construction will go into the 800s.

The sail has nothing to do with wind power, but the Navy likes using old words for things. Rather, its purpose is to house the masts of the submarine. Blueback‘s sail contains the submarine’s two periscopes, radar antenna, high/low-frequency antennas, ECM/DF antennas, and the snorkel. They are currently displayed in their extended position, but they would fully retract down into the sail when the submarine submerged.

Here are the masts that are currently extended:

- Observation Periscope – The forward-most periscope. It would be the larger of the two, but this is not the original Type 8 observation periscope from my understanding. (The original observation scope was removed because it had classified ECM intercept equipment on it.)

- Attack Periscope – This is a Type 2 periscope. It is physically smaller in profile to make it harder to detect. It would also have an Ultra High Frequency/Identification Friend or Foe (UHF/IFF) antenna operating in the 200 – 500 MHz frequency range. (This is also not the original attack scope.)

- AN/BRA-11 & AN/BRA-19 – The BRA-11 is a helical antenna and the BRA-19 is a telescoping whip antenna. These are High-Frequency (HF) transmitters operating in the 2 – 32 MHz frequency range. Both are capable of receiving in the low, medium, and high-frequency ranges.

- BRD-6B – This is a Radio Direction Finder (RDF) and Electronic Countermeasures (ECM) mast. It can be used for navigation and radio surveillance.

- AT/317E (AKA the football) – This is a Very Low Frequency (VLF) loop antenna capable of receiving signals up to 90 feet underwater.

- Snorkel – This contains the air induction valve at the very top and the exhaust just under the plate (AKA batwings) about halfway down. There is also an AT-497/UHF whip antenna on the top of the snorkel.

There are two more masts in the sail that are currently not raised. One would be the AN/BPS-12 surface search/navigation radar antenna next to the BRD-6B antenna. The other would be the AN/BLR ECM/ESM mast (for radar interception and direction finding) between the AT/317E and BRA-19 antennas. This mast is distinct from the BRD-6B antenna. The reason these masts are no longer extended is that they lost hydraulic pressure during Blueback‘s last drydocking in 1998. (Further discussion of the ECM/ESM system below.)

There is also an access trunk in the forward part of the sail which leads to the bridge at the top. It is about a 25-foot climb to the top of the sail from the control room, but the sail is not a conning tower like on WWII fleet boats, and it is not a habitable space. The interior of the sail that houses the masts is actually free-flooding. The bridge trunk can be accessed from inside the control room, just forward of the periscopes. (Tours are not allowed up in the sail or on the bridge given the vertical ladders and lack of space. The only reason staff go up to the bridge is to perform maintenance.) This is also not an entrance/exit to the submarine, either today or when it was in service, because there is no way to get to the top of the sail from the outside without lowering a rope ladder.

After climbing up through the two hatches in the trunk, you come to a small landing that has two doors on the port and starboard side. These lead out to the fairwater/sail planes. Another small ladder from that landing goes up to the bridge. Currently, most of the space on the bridge is taken up by a heat pump that is part of the museum’s HVAC system for the submarine. From the keel to the top of the sail is 48 feet 2 inches. (The distance from the keel to the main topside deck is 29 feet 3 inches.)

You may notice that the sail has various circular or oval plates on the side. These are placed in specific areas to access the masts (either when raised or lowered) when they need maintenance and repair. The sail itself is free-flooding since air bubbles would create noise as the sub dives. Only the access trunk would need to remain watertight and withstand the water pressure at depth.

Hull

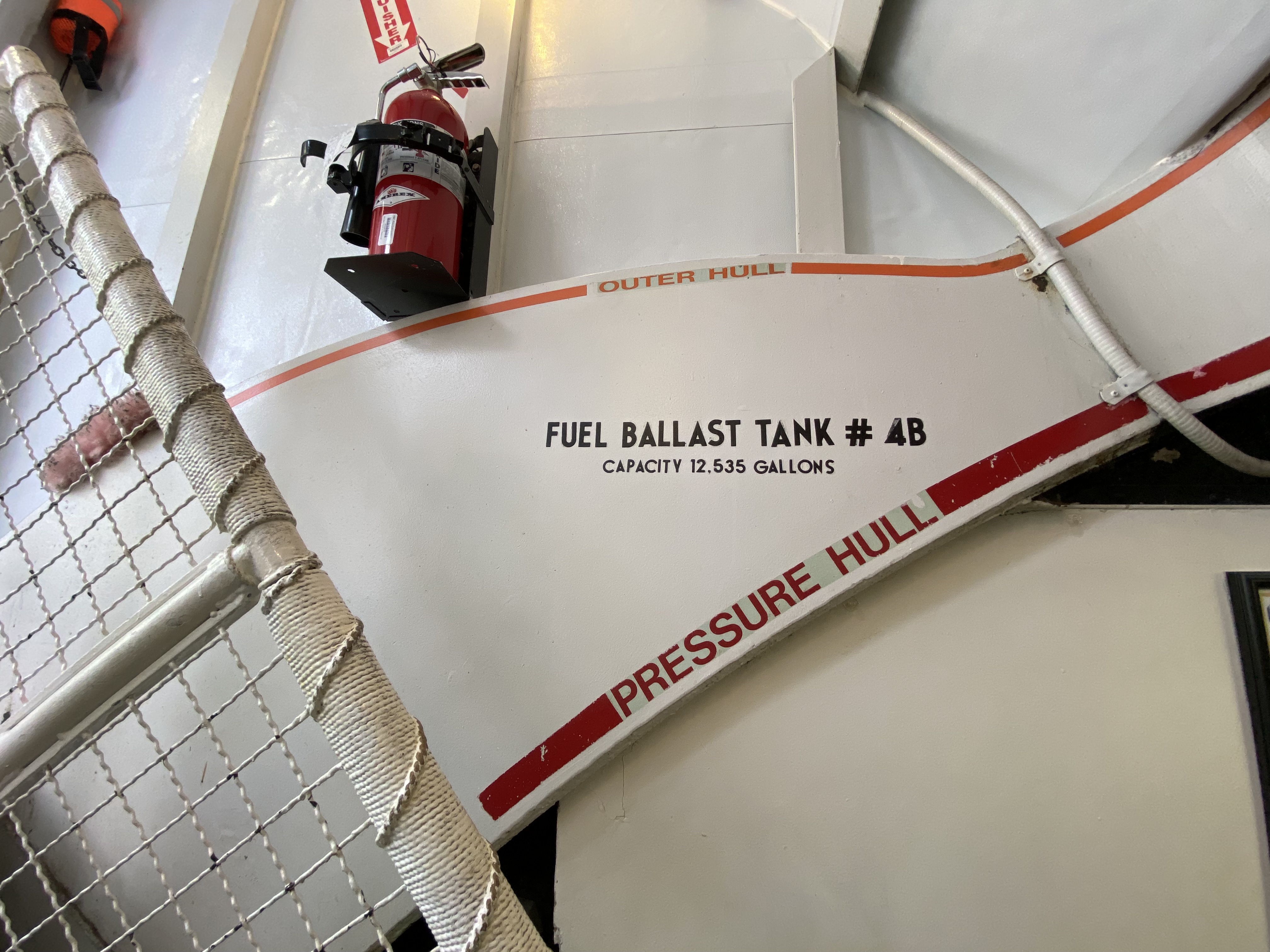

Physically Blueback is 219 feet 6 inches long and 29 feet wide at the beam. She displaces around 2,158 tons on the surface and 2,649 tons submerged. The hull is made of HY80 which is a high-tensile, low-carbon steel composed of a combination of nickel, chromium, and molybdenum (along with various other trace elements). “HY” means High Yield and “80” means it can withstand 80,000 pounds of pressure per square inch.6 Blueback is a double-hulled submarine with the outer hull being 0.75 inches thick, and the inner pressure hull being 1.5 inches thick. Her normal operating test depth is 712 feet, with a calculated 50% margin of safety, so it can go deeper. However, around 1,050 feet the submarine is going to implode. It does not necessarily mean that once you hit 1,050 feet, the hull will automatically just give way and collapse, as the actual crush depth is not really known, but you do not want to find out exactly where that is. If it is any consolation, the implosion of a submarine would occur instantaneously. You would not even know what hit you.

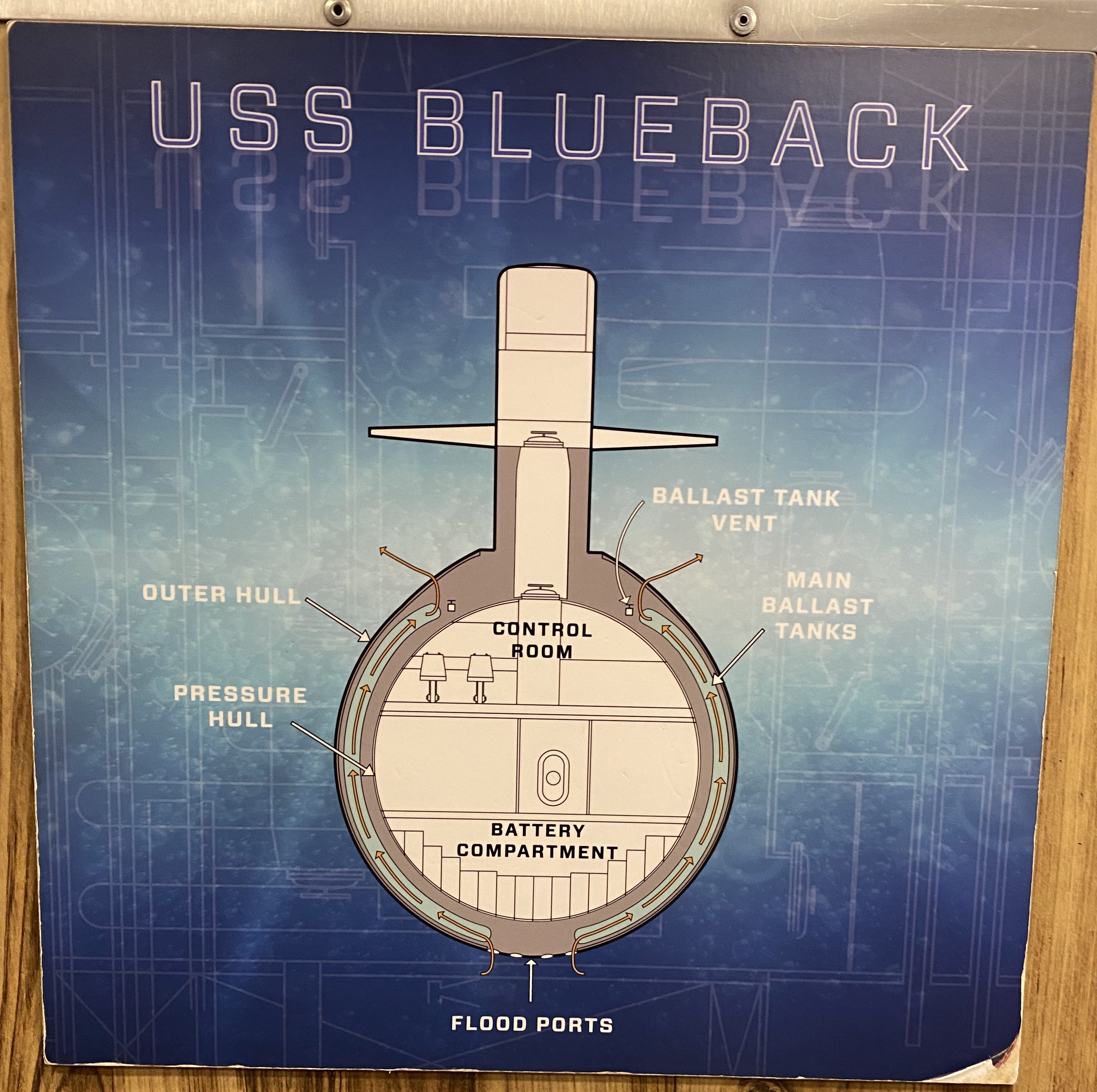

Between the two hulls are various tanks; six of which are the main ballast tanks. There are a series of flood ports on the bottom of these tanks that are open to the sea at all times and a series of vents on the top of the hull. When the vents are open, the air inside the ballast tanks escapes, and seawater floods in. Blueback takes on about 490 tons of seawater for ballast, and then the submarine will dive or submerge. It does NOT sink; that is considered a bad thing. “Sink” is what Titanic did after it found the iceberg in the Atlantic. That is a one-way trip and submarines want to avoid that scenario.

The sub is controlled underwater via a rudder and two sets of planes. The rudder is actually two symmetrical parts (upper and lower) that go through the centerline of the stern. The rudders have a maximum angle (left or right) of 37 degrees, but normally 35 degrees. Sticking out of the side of the sail are the fairwater planes (AKA sailplanes). These pivot up and down along their long axis and are used to control the depth of the submarine underwater. Originally, she had bowplanes, but these were moved to the sail in 1964, a few years after her commissioning.7 The fairwater planes have a maximum angle of travel of 22 degrees (up or down), but normally 20 degrees, with an average rate of travel of 5 – 9 degrees/second. The other set of planes, called the stern planes, are on the back of the submarine perpendicular to the rudder; although they cannot be seen because they are underwater. The stern planes control the angle of the boat when she is submerged. They have a maximum angle of travel of 27 degrees (either rising or diving), but normally 25 degrees. Both sets of planes move together since they are linked via the hydraulic rams. In other words, the sailplanes cannot move independently of each other (same with the stern planes).8

The gap along the length of her hull is called a turtleback.9 Essentially, it is a fairing that covers the upper portion of the outer hull and provides a flat surface to walk on when the submarine is on the surface. Otherwise, the outer hull is a completely cylindrical tube. Beneath the turtleback are pipes and other deck equipment that are stored there. If you look at a modern Ohio-class ballistic missile sub, you will also notice a turtleback that covers the tops of the missile tubes. The turtleback also means that Blueback is (technically) not a true Albacore-type hull. If you compare the two submarines, the USS Albacore‘s hull is distinctly more streamlined.

The hull of Blueback had pylons welded onto it which are secured into railings within triangular steel pilings that are sunk into the riverbed. Since the submarine (along with the dock) is floating on the river, this allows it to move up and down along the pilings with the water level. This is important because, in late January and February 1996, the Willamette River flooded. The water level became so high that it went over the bank of the esplanade and flooded the basement of the museum! The ramp that allows access to the sub was submerged. (The dock floated up along the green pilings in the river.) Blueback remained afloat, but she nearly reached the tops of the steel pilings and reportedly a tugboat had to be brought in to make sure she did not break free and float down the river. Following that flood, the tops of the green pilings were extended an additional four feet.

Admittedly, the boat does look a little grimy (as of 2025). It is technically overdue for drydocking where the hull will be cleaned, repainted, etc. The last time Blueback was drydocked was in 1998 and museum ships are generally drydocked around every 20 – 30 years. However, the sheer expense means that it is unlikely she will be drydocked anytime soon.10

Hawaii Five-O

Blueback had a short cameo in the 1968 TV series Hawaii Five-O in Season 1, episode 5, titled “Samurai.” She was homeported in Pearl Harbor at the time. Reportedly, the show’s producers wanted to film a nuclear-powered submarine, but the Navy said:

Instead, they allowed them to film on Blueback, which looks similar to many nuclear fast-attack boats. In the episode, Steve McGarrett (played by Jack Lord) drives up the pier and goes aboard to talk to a Chief Petty Officer. He drinks some coffee and then heads back ashore.

The Screw

Next to the main building of the museum is the submarine’s fixed-pitch 5-bladed screw. This propeller is 11,002 lbs. of aluminum, manganese, and bronze, making it corrosion-resistant, and is 12 feet 6 inches in diameter.

Currently, the screw serves as a memorial, and on the bricks around the base are the names of the U.S. submarines that have been lost in service. One brick directly behind the screw notes that there is a time capsule beneath the screw that will be reopened on 24 August 2050. However, I have no idea what is inside it.

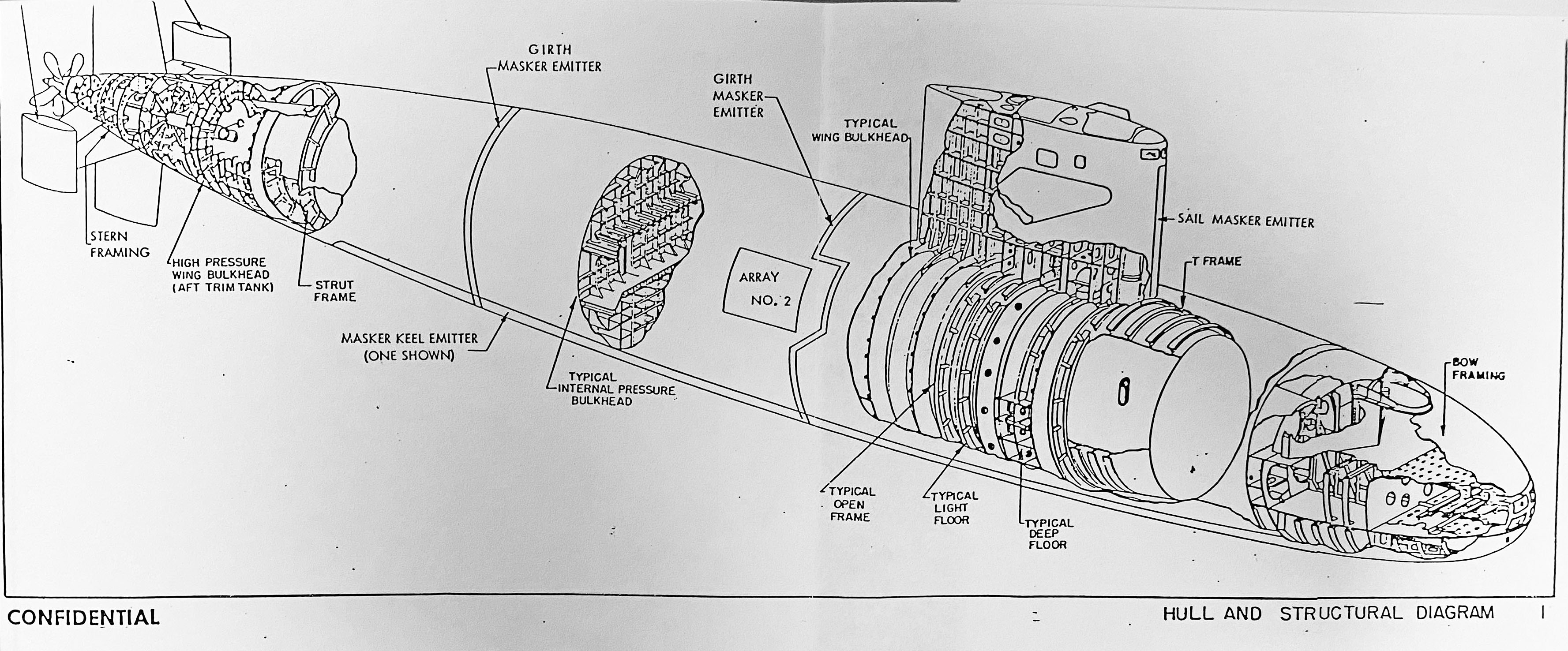

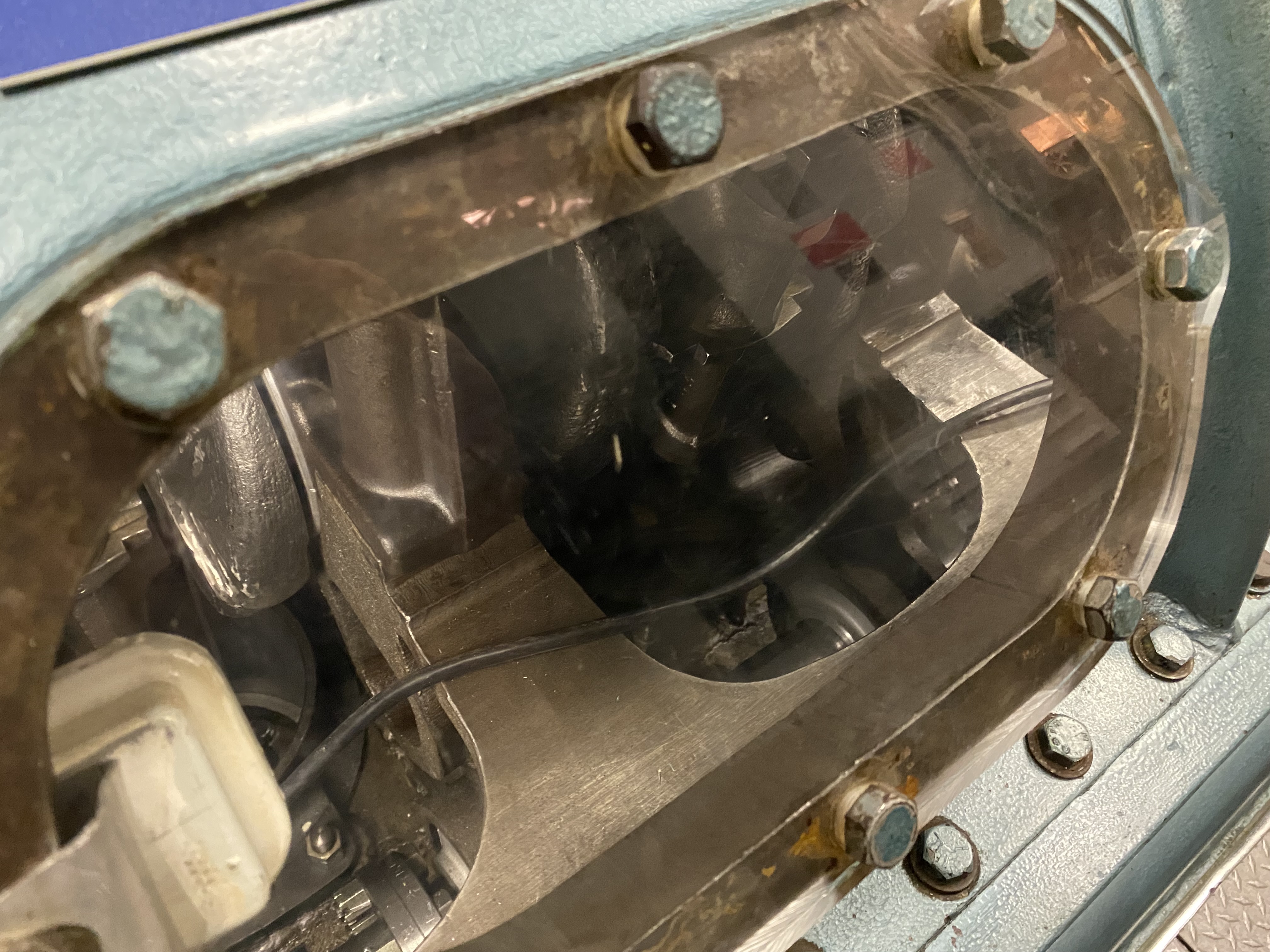

Prairie-Masker System

Note that the blades have small holes around their edges. This is actually the PRAIRIE part of the Prairie Masker system. PRAIRIE is an acronym for Propeller Air-Induced Emission. Compressed air is pumped through tiny holes on the edges of a propeller blade to reduce the noise of cavitation. Cavitation occurs when a moving propeller blade creates an area of low pressure behind it, which is less than the vapor pressure of water at that particular depth. Essentially, the lower pressure area is causing the water to boil at a lower temperature. This causes water vapor bubbles to form, which then collapse when they leave that low-pressure area and move into a high-pressure area. These collapsing bubbles create a loud noise, and they can also cause damage to the propeller over time. However, if the edges of the propeller are emitting air bubbles themselves, then the bubbles resulting from cavitation will have some air inside them, so the collapsing water vapor doesn’t completely close the bubble. This creates far less noise.

As further explained by a former submarine captain:

For a given propeller, cavitation is a function of its depth (pressure), speed (RPM), and water temperature. The blade moving closest to the surface is at the lowest sea pressure, so its cavitation, if present, will be greater. Counting the pulses of sound will allow a Sonar Technician to determine the blade rate. By determining the number of blades, he/she can calculate RPM. Deformities or nicks in one propeller blade may cause an earlier onset of cavitation than in the others. The implosion of the bubbles may also cause pitting or erosion of the blades at the points of cavitation, a major problem with some surface ships. Since nuclear submarines mostly operate fast only when deep, cavitation is usually not a major concern except when accelerating.11

The masker system is a series of bands around the hull and on the leading edge of the boat’s sail that also emit a curtain of bubbles around the sub. The idea with the masker system is to cause any radiated sound from the boat to be dampened or reflected back by the bubble curtain.

According to the piping tab, Blueback‘s masker system is composed of three girth emitters around the hull at frames 22, 44, and 51. There are also emitters on the keel from frames 21 to 74, as well as an emitter on the front of the sail. These all use 60 psi air.

The Prairie-Masker system did have limitations. Firstly, it could only be used when the submarine was snorkeling since it needed to intake a lot of air for the air compressor to run this system. Secondly, it was reportedly a maintenance nightmare and did not really work as advertised. Thirdly, a sonar technician hearing the Prairie-Masker system will not likely be fooled by it. While it is intended to sound like a rain squall, the issue is that the sound covers a very narrow area of only a few degrees, whereas an actual rain squall will cover something like 20 degrees. It is also moving in a very specific direction and speed, and you can still count the blades and number of screws on a contact and be able to classify it as a certain type of vessel (merchant, destroyer, etc.). That said, there is reportedly at least one account of an ASW exercise where the organizers asked the submarines to turn off their Prairie-Maskers so the surface sonar technicians could better hear them. So either these sonar techs were inexperienced, or there was some value to the Prairie-Masker system. The use of Prairie-Masker on U.S. diesel-electric submarines ended sometime in the 1970s. Former crewmember Rick Neault notes that when he reported aboard USS Bonefish (SS-582) in 1984, she no longer had that system.12 Today, Blueback still has some components of the Prairie-Masker system, such as the air compressor in the engine room.

Interior

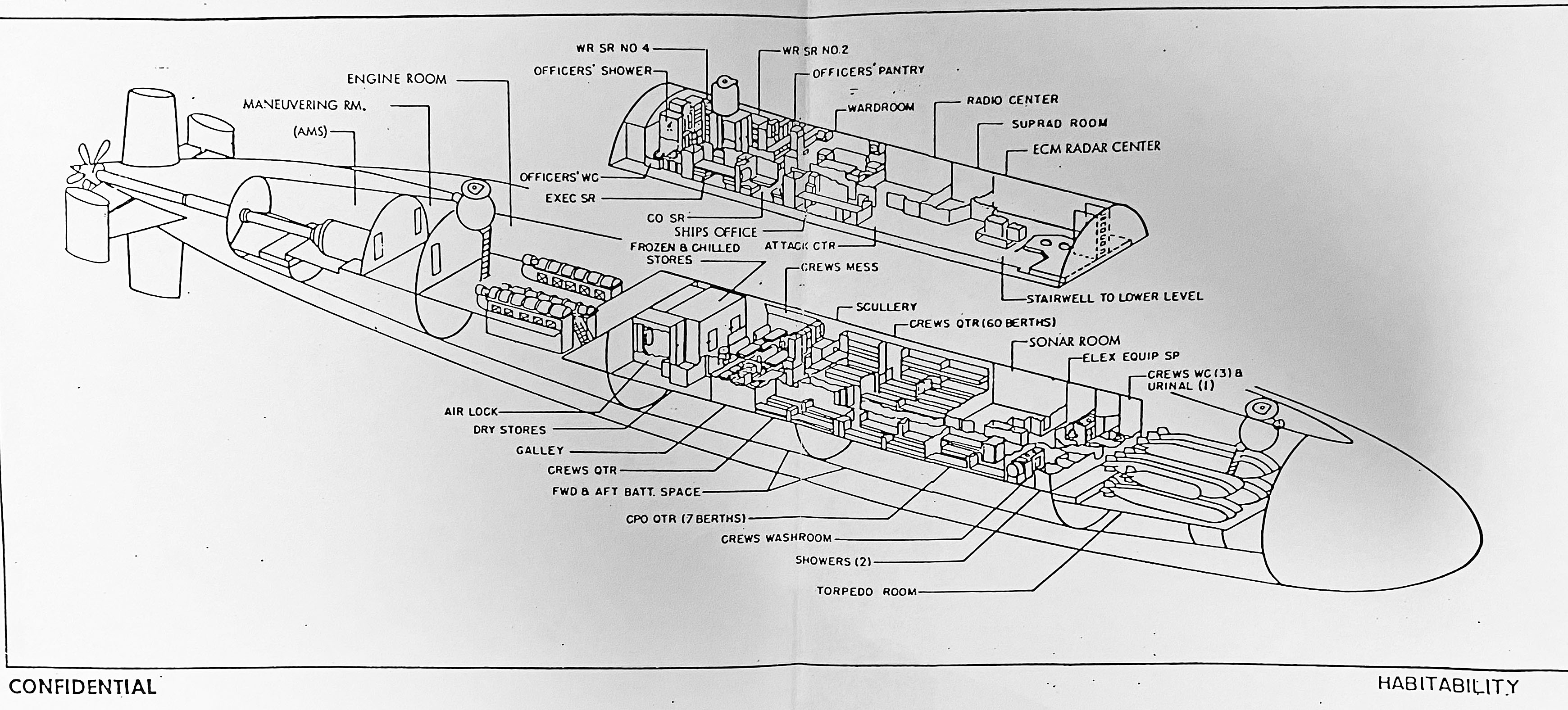

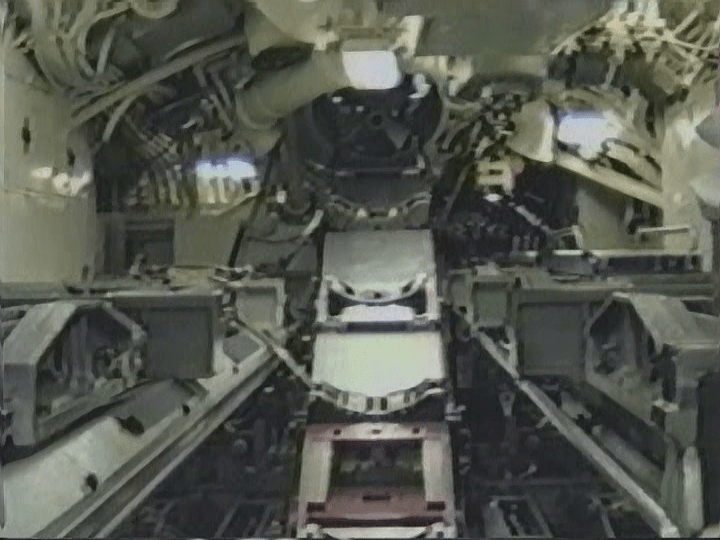

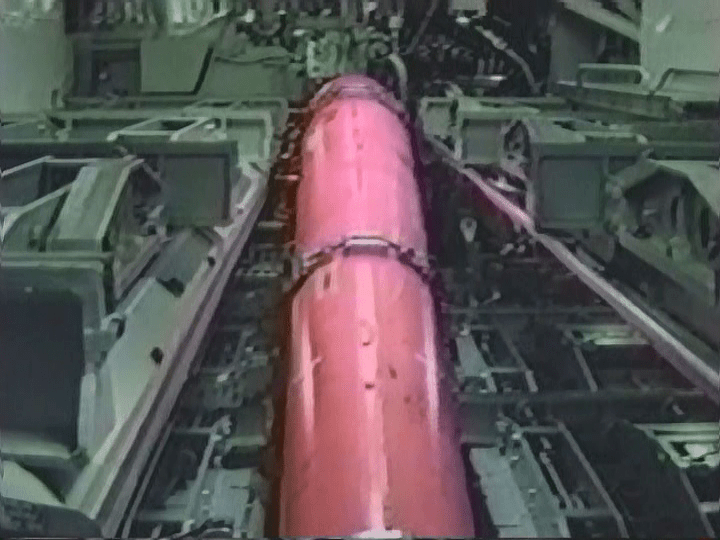

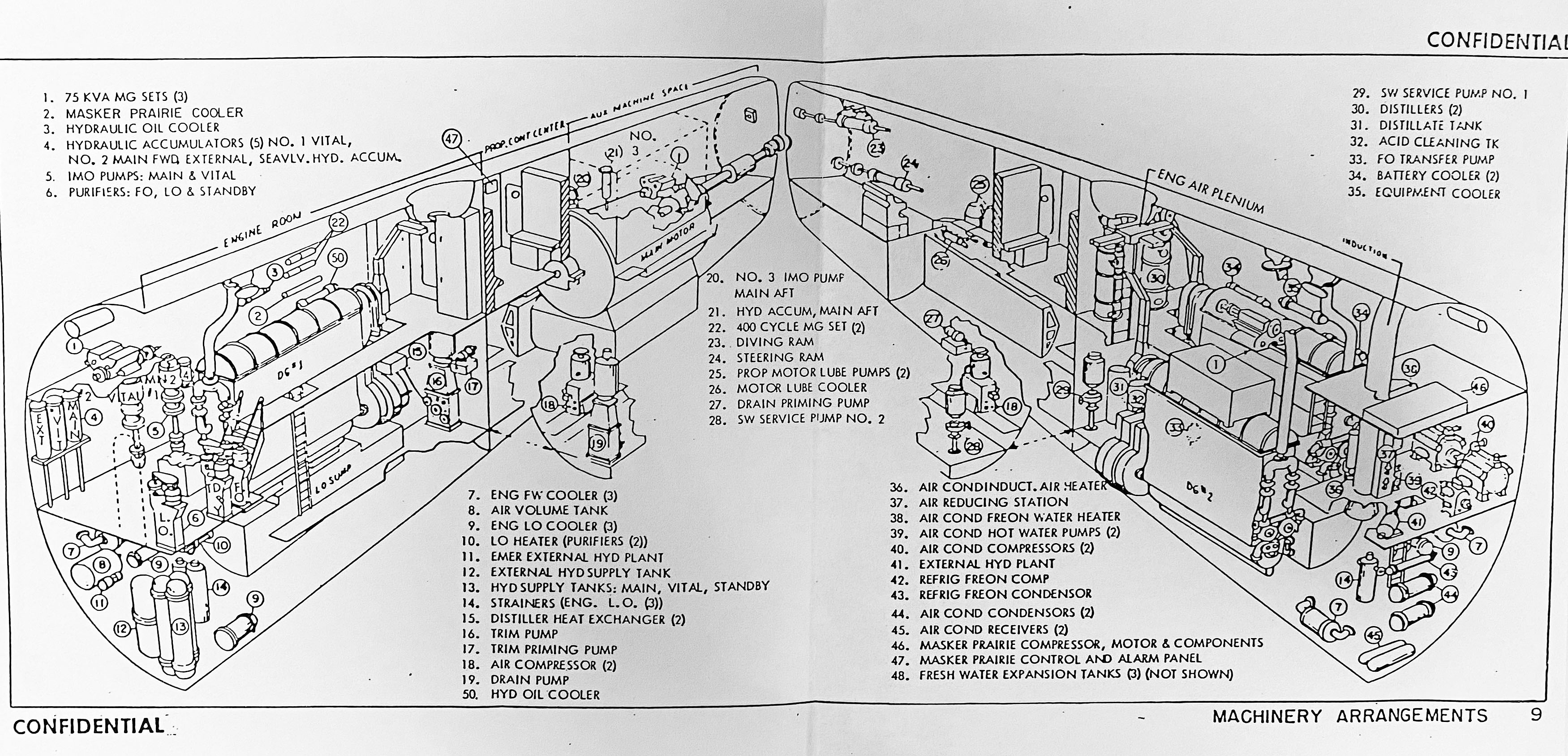

The interior of the submarine is divided into three watertight compartments which contain the various rooms. The midship compartment is the largest and houses the habitable areas of the submarine, along with the control room, radio room, yeoman’s shack, sonar room, heads, showers, galley, scullery, crew’s mess, store rooms, and battery compartments. The forwardmost (and smallest) watertight compartment is the torpedo room. The aftmost watertight compartment is the machinery compartment. It contains the engineering spaces of the sub, including the diesel engines, maneuvering room, pump room, and auxiliary machinery space with the electric motor and propeller shaft. Nominally, the submarine would have a crew of 85 men (8 officers and 77 enlisted).

Officer Country

The first area upon entering the boat is Officer Country. You can tell because of the blue carpet. This is the most comfortable area on the boat, and throughout the rest of the boat, every piece of equipment was placed intentionally, and often simply because there was space to put it there. Anyone on the submarine will quickly realize that the Navy prioritizes the accessibility of equipment over comfort.

All the wood paneling you see in the submarine is actually Formica laminate with a wood pattern. It was certainly nice for the time, but now it makes the area look like an RV that got stuck in the 1970s. There were originally four officer’s staterooms in total. Two three-man staterooms for the junior officers, the Executive Officer’s (XO) stateroom, and the Commanding Officer’s (CO) stateroom. The museum’s entrance and exit stairs to the submarine go through what used to be one of the three-man staterooms, and the other one has been converted into an office. The XO’s stateroom is currently used by the museum staff as a break room. Only the CO’s stateroom is made up to appear as it would have been when the boat was in operation. The CO’s stateroom is the largest; roughly the size of a small walk-in closet. It is the only stateroom with a lock on the door, as well as a single bed. The CO also has the largest bed (about 6’5″ long and 2’9″ wide), and it is also the only built-in bed that you can sit up in and not hit your head on anything. The CO is the only person on board who would have his stateroom all to himself. Even if an admiral or visiting dignitary, such as the President, was aboard, they would share the XO’s stateroom which has an additional fold-down rack in it. (An attack sub like Blueback would have a Lieutenant Commander or Commander as the commanding officer. The Commanding Officer of a vessel, regardless of rank, is always addressed as the “Captain.” Even if a higher ranking officer is aboard, they are a guest on the submarine and do not supersede the captain’s command.) At the very aft end of Officer’s Country, on the starboard side, is one head and one shower, specifically for the officers.

Also in this area are the officer’s pantry and the wardroom. The food for the officers is prepared down below in the galley and sent up via a dumbwaiter to the pantry, where an enlisted steward prepares and serves it to the officers in the wardroom. The pantry is not a galley (kitchen), and no food is cooked in there except coffee and snacks. The original equipment in the pantry would be as follows:

- 1 warming oven

- 1 hot plate

- 1 toaster

- 1 coffee maker (12 cup capacity)

- 1 five-cubic-foot refrigerator

- 2 sinks

The steward would be the only enlisted man allowed in officer country; all the other enlisted men would need to have some reason for being there; probably because one of the officers wants to have a “chat” with them. (Even today, the pantry continues to serve as a meal prep location for the museum tour guide staff. It has an industrial-grade microwave and a highly advanced coffee machine…also known as a Keurig, but obviously, that is not original to the submarine. It is so complex that I once taught a retired submarine captain on the tour staff how to use it.)

The wardroom is the dining and recreation area for the officers. It is just a large table. There used to be a bench on the inboard side, but that was removed when she was converted into a museum ship. (We tour guides often say that the wardroom table seats up to 27 people. This seems like hyperbole, but one of us actually managed to do that with a school group of first graders. So as long as everyone is six years old, then it will work.) Normally, the Commanding Officer would sit at the end closest to the pantry while the Executive Officer sat next to him and the Supply Officer sat at the other end of the table. During meal times, nobody would start eating until the senior officer took the first bite.

The wardroom table is also the largest table on the sub and serves as the operating table and battle dressing station in medical emergencies or when at battle stations. The large lamp overhead is an operating lamp. The problem is that there would be no doctor on board the sub. There is only a Hospital Corpsman. The basic training for a corpsman is an intensive 14-week program teaching the basics of emergency medical procedures, disease pathologies, and nursing techniques. According to the Navy Medicine website, to become a corpsman on a submarine requires the corpsman to be at least an E-5 (Petty Officer 2nd Class), they must pass the physical to serve on subs, then go through a further year-long training program to become an Independent Duty Corpsman (IDC). This includes 6 weeks at the Basic Enlisted Submarine School (BESS), 8 weeks of schooling in radiation health, and 44 weeks of studying clinical and operational health procedures to manage a submarine crew’s medical needs.13 They are essentially a combination of an EMT and a physician’s assistant. Most of what the corpsman does is patch up bumps, bruises, and cuts, which are the most common injuries aboard a submarine. They would also monitor the mental health of the crew. Even then, they can do everything from dispensing aspirin and suturing wounds to removing a person’s appendix. Reportedly, an appendectomy has been performed in the wardroom on Blueback. The corpsman was operating on the patient while an assistant was next to him and reading the procedure out of a medical textbook. There was also a phone-talker with a direct line to the Captain. Once the corpsman finished up the stitches, the phone-talker informed the Captain, who ordered the submarine to be surfaced, and the man was medevaced to a hospital.

Possibly the first instance of an appendectomy performed on a submarine occurred during WWII in September 1942 when Pharmacist Mate Wheeler Lipes removed Seaman Darrell Rector’s appendix aboard USS Seadragon (SS-194). While Rector survived the operation, he did not survive the war; he was killed when USS Tang (SS-306) was sunk by her own circular running torpedo in October 1944.14

Another surgery done on the wardroom table of Blueback was the treatment of a foot injury. The deck log from 18 February 1970 indicates that QM3 Verdel Myers was working up in the sail on the magnesyn compass while the sub was surfaced. Myers got his foot inadvertently caught in one of the hydraulic rams for one of the sail planes (which were moving for some reason even though the sub was surfaced), and suffered a “traumatic amputation of his right toes.” Ouch! The corpsman treated his foot wound and reportedly had to perform a partial amputation. Myers was later medevaced via a Coast Guard helicopter to Tripler Army General Hospital.

Becoming a Submariner

Everyone on a U.S. Navy submarine, both officers and enlisted, are volunteers. Nobody is just assigned to a submarine. After boot camp, selected enlisted personnel go to eight weeks of Basic Enlisted Submarine School (BESS) in Groton, Connecticut. That school teaches you just enough about submarines to make you dangerous. Most of the curriculum is focused on basic submarine organization, operation, damage control, and escape procedures. During BESS, students go through three damage control trainers to simulate three specific casualties. These are the firefighting, flooding, and submarine escape trainers. In addition, you will have to pass the psychological and physical screenings to ensure you are fit enough to serve on submarines. Obviously, claustrophobia would not be a great thing to have for prospective submariners.

For officers, the submarine service gives a higher preference to people with degrees in hard sciences because they are required to know about metallurgy, mathematics, physics, nuclear reactors, etc. Following their commissioning program, officers go through a series of interviews with a panel that includes the Director of Naval Reactors (a 4-star admiral) to assess their knowledge and ability to handle stress. If selected, they go through a more intensive training pipeline than enlisted personnel. Since all U.S. Navy subs are nuclear-powered, this involves 6 months at the Naval Nuclear Power School (NNPS), which is basically a graduate-level course on the science and mathematics behind nuclear power, followed by another 6 months in a Nuclear Power Training Unit (NPTU), AKA a “prototype.” These are the land-based nuclear reactor prototypes before the design was installed in submarines. Here, the officers apply the concepts they have learned to an actual reactor. Then comes 3 months in the Submarine Officers Basic Course (SOBC). This is basically the officer’s version of BESS, and this is all before they even get to their first boat! (The only enlisted sailors who attend NNPS are those who will work on the reactors, such as on submarines or aircraft carriers.) Upon being assigned to their first boat for 2 – 3 years, the officer has to qualify and earn their dolphins. They’ll also stand watches and lead a division of sailors under them. Eventually, the officers will have to pass the engineering exam, which will qualify them as the chief engineer of a submarine. This is the first major test to see if the submarine force wants this officer to stay or go do something else in the Navy. Assuming they pass, they then work their way up the pipeline in their careers on submarines. Following their first tour on a submarine, the officer, by now probably a Lieutenant (O-3), will head to a shore assignment, perhaps teaching at a naval school or on the staff at a sub squadron.

Officers who want to command a submarine enter a long pipeline that includes the 6-month-long Submarine Officers Advanced Course (SOAC), which will prepare them to act as a department head on a boat. This is followed by a 3-year-long tour as a department head, after which the officer must attend a 3-month-long Prospective Executive Officer’s (PXO) course. By now, this officer is likely a Lieutenant Commander (O-4) and they’ll then serve as the XO of a boat. Another shore assignment awaits the officer, which includes graduate-level education at a joint billet, for example, a staff college or the Naval War College. Upon being selected and promoted to Commander (O-5), the officer will attend the 6-month-long Prospective Commanding Officer’s (PCO) course, during which they’ll practice the intricacies of commanding a nuclear submarine, practice approaches, fire several live weapons (torpedoes and missiles), and learn about additional missions of a submarine, including strike warfare, intelligence gathering, mining, etc. If they pass, then one day they’ll become the Commanding Officer (CO) of a submarine. These steps all occur over the, say, 15 – 20+ year career of an officer. They are not designed to be easy, and they weed out those who will not make good skippers.15 The process is similar for those who wish to become commanding officers of other military units in other services (air, naval, or ground forces).

Once you get to your first boat, your next task is to qualify on it. At this point, you are what is known as a “non-qual,” or more colloquially/derisively as a “NUB” (Non-Useful Body), a “puke,” or an “oxygen stealer”. (i.e. you are a danger and a liability to this submarine and its operations.) On average, it takes approximately 9 to 12 months to qualify on a Barbel-class boat. (A former sailor on USS Barbel told me he managed to qualify in just over 60 days!) To become qualified, you need to know every system on the submarine and the basics of everyone else’s job. This includes the buttons, switches, valves, pipes, wiring, how to use the equipment, and what to do in various emergencies. You are walked through the boat, you have to identify various pieces of equipment by sight, explain what it does, and get signed off on a qualification sheet, which can easily have upwards of 100 signatures. Much of the information is based on the safety equipment and damage control. You will then go before a board of officers and enlisted and answer their questions for several hours. You will have to draw out diagrams of things like piping and wiring to the satisfaction of the panel, who then decide whether or not to recommend you for qualification to the Commanding Officer. The qualification process for officers is similar, but more involved, and includes knowledge of engineering and how to drive and fight the sub.

So if you know what is good for you, you will spend all your free time with your nose in one of the many technical manuals. If you are reading something for pleasure, someone will snatch that book out of your hands and replace it with a technical manual. In fact, you probably would not be allowed to eat any ice cream, watch movies, or do any of the “fun” stuff until you get qualified. The reason for this qualification process is to build redundancy into the training of the crew. Everybody knows the job of everyone else. Yes, you have your rating that you specialize in (like a sonar technician, quartermaster, machinist mate, etc.), but you need to have a working knowledge of all the systems on the sub. If you go to a different class submarine, you must requalify, but it is generally considered easier the second time around.

Upon successfully getting qualified, you earn your submarine warfare pin, AKA “dolphins” or “fishies,” as they are sometimes called. Gold is for officers, and silver is for enlisted. You officially become a member of the crew and a qualified submariner. If you are wondering why the dolphins on the pin look strange, it is because they are not the dolphin mammal. They are dolphinfish AKA mahi-mahi. There is a display on the back wall in the wardroom that shows the submarine warfare pins of 48 countries that have or had submarines in their navies.

The blue-paneled display in the wardroom shows seven scale model submarines. Blueback is second from the top and one of the smallest submarines. Below is a Gato-class WWII fleet boat. These are 311 feet long and displace roughly 2,400 tons submerged with a crew of roughly 60 men. The Barbel-class, with its teardrop hull design, replaced the fleet boats. The big one at the top is an Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine. These are the largest submarines in the U.S. Navy at 560 feet long (about 2.5 Bluebacks long) with a submerged displacement of about 18,000 tons; they have a crew of roughly 150 or more. 18 were made, but the 4 oldest ones were converted into guided-missile subs. Third from the bottom is a nuclear-powered Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine.16 These are 362 feet long, displace about 6,900 tons submerged, and have a crew of roughly 130. The LA boats are the workhorses of the U.S. submarine fleet. 62 were built, but they are being slowly decommissioned and replaced with the newer Virginia-class boats. Second from the bottom is the Block V Virginia-class fast attack submarine. These are 460 feet long and displace roughly 7,800 to 10,200 tons. The first Block V boat, USS Oklahoma (SSN-802), was laid down in August 2023 and is under construction as of January 2025. At the very bottom is a Soviet/Russian Typhoon-class ballistic missile submarine. At 564 feet long, 76 feet at the beam, and with a submerged displacement of roughly 48,000 tons, these were the largest submarines ever built. All six were commissioned in the 1980s, and as of February 2023, we believe all have been taken out of service.17 The small submarine model on the left is the first submarine commissioned by the U.S. Navy in 1900; USS Holland (although technically the 4th sub owned by the Navy).18 Named after its inventor, John Holland, it is 53 feet long and had a crew of 6 men. One important thing we learned from USS Holland is not to use gasoline engines in submarines because the fumes are too explosive. To put all of these boats in perspective, a 40-foot city bus is beneath the Holland.

Radio Room & Yeoman’s Shack

Moving forward, just beyond the door from the wardroom are two rooms on either side of the passageway. These are the radio room on the port side and the Yeoman’s Shack on the starboard side.

The radio room would operate the various high-frequency and low-frequency transmitters and receivers. All communications with the outside world would go through this room. Further forward inside the radio room, behind a curtain, is the “crypto room.” This room houses the cryptographic equipment. If there were “spooks” (Cryptologic Technicians or intelligence officers) onboard, they would be working in the crypto room to decode/encode secret and top-secret communications. According to the late Commander “Stu” Taylor, a former engineering officer on Blueback, about 6 – 8 spooks might be aboard. In fact, the entire radio room is a restricted area and most crew would not be allowed near it because it contains some of the most top-secret equipment on the boat. If you had to work in here for some reason and you were not a radioman, then you would need to have an escort to keep an eye on you while you did whatever work was needed in here.

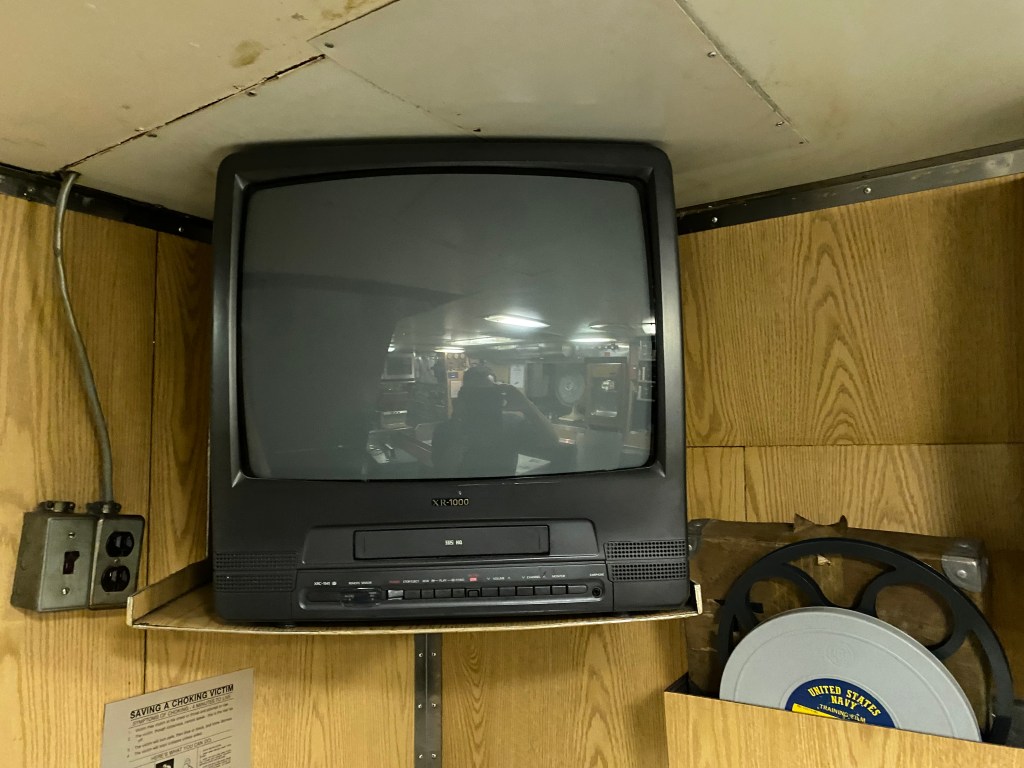

Much of the original radio equipment has been removed, but currently, the radio room still functions as an active transmitting station for a local amateur radio club with the callsign W7SUB, and it does use the submarine’s radio antennas (at least partially). While it was not used much during the pandemic, OMSI radio operators have recently begun using it more frequently. They can contact museum ships around the United States, and one operator said he even briefly contacted a station in France.

The Yeoman’s Shack is simply the ship’s office. A Yeoman handles the vessel’s clerical and administrative work. In some ways, the Yeoman is one of the more important behind-the-scenes people on any vessel. They handle all the paperwork and documentation for everyone onboard. Much like the secretaries/administrative assistants in large organizations, they know everything about what goes on. Be nice to the Yeoman because they make sure you exist on paper and get paid. If you want to request leave, then they might be able to expedite your paperwork…if they like you.

IC Alley

The passageway that connects the wardroom to the control room is colloquially referred to as “IC Alley.” It houses the switchboards for the interior communications equipment, alarm and signal systems, lighting, and fire control. Basically, anything on the sub that was powered electrically, including the Mk 19 gyrocompass, would have switches here to energize or de-energize them.

Since this submarine operated in the days before computerized voyage management systems, navigation was done with a traditional sextant, paper charts, radio, and early satellite navigation. According to tour guide Tony Capitano, our former USS Barbel sailor (a former IC electrician/Missile Technician), the main gyrocompass was very accurate and rarely needed to be reset.

Behind the main gyrocompass is the winch for the Very Low Frequency (VLF) radio cable. This 1,000-foot floating cable could be streamed behind the submarine when it was submerged down to test depth to receive communications. It would float just below the surface so as not to give away the position of the submarine.

Tony Capitano also notes that the layout of IC Alley and the Control Room was significantly different on his sub compared to Blueback. For one thing, the crypto room was not connected to the radio room. The radio room on USS Barbel simply had a bulkhead where the door to the crypto room was on Blueback. Next to IC alley, and accessible behind the main gyrocompass, would be the sonar room. Where Blueback‘s sonar room is, at the bottom of the ladder below the control room, was the Chief Petty Officer’s quarters on Barbel. Apparently, the three boats had slightly different internal layouts since they were built by different shipyards. Additionally, Barbel was reportedly outfitted as a radar picket sub, and Bonefish was outfitted as a missile guidance sub for Regulus missiles.19

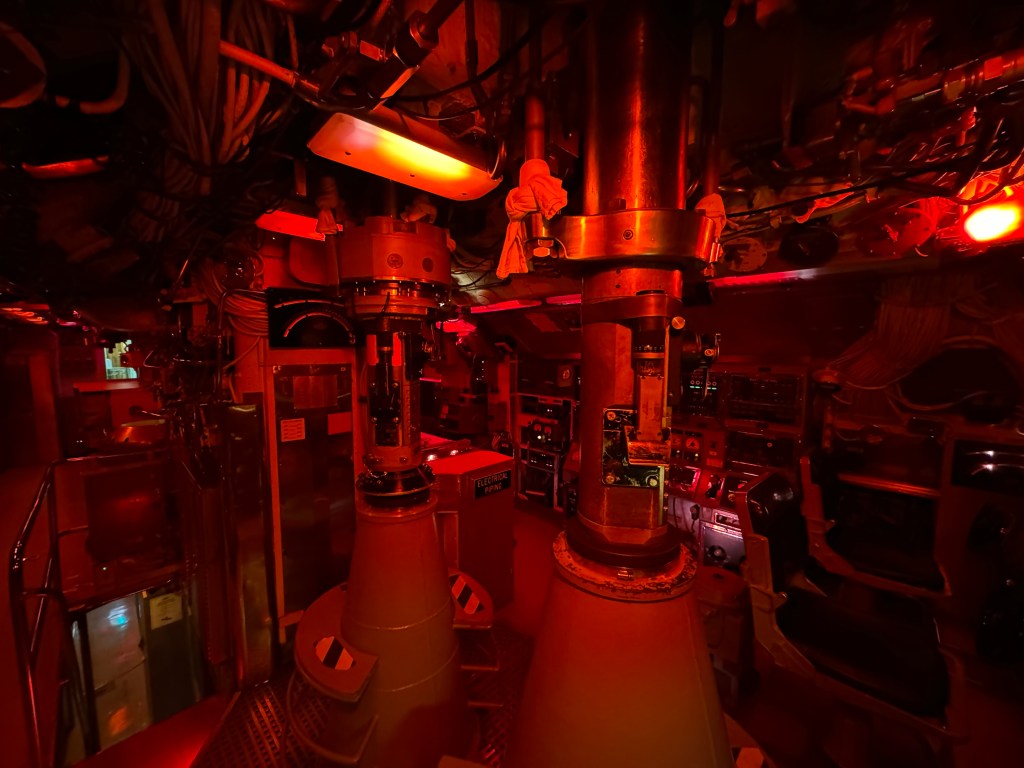

Control Room

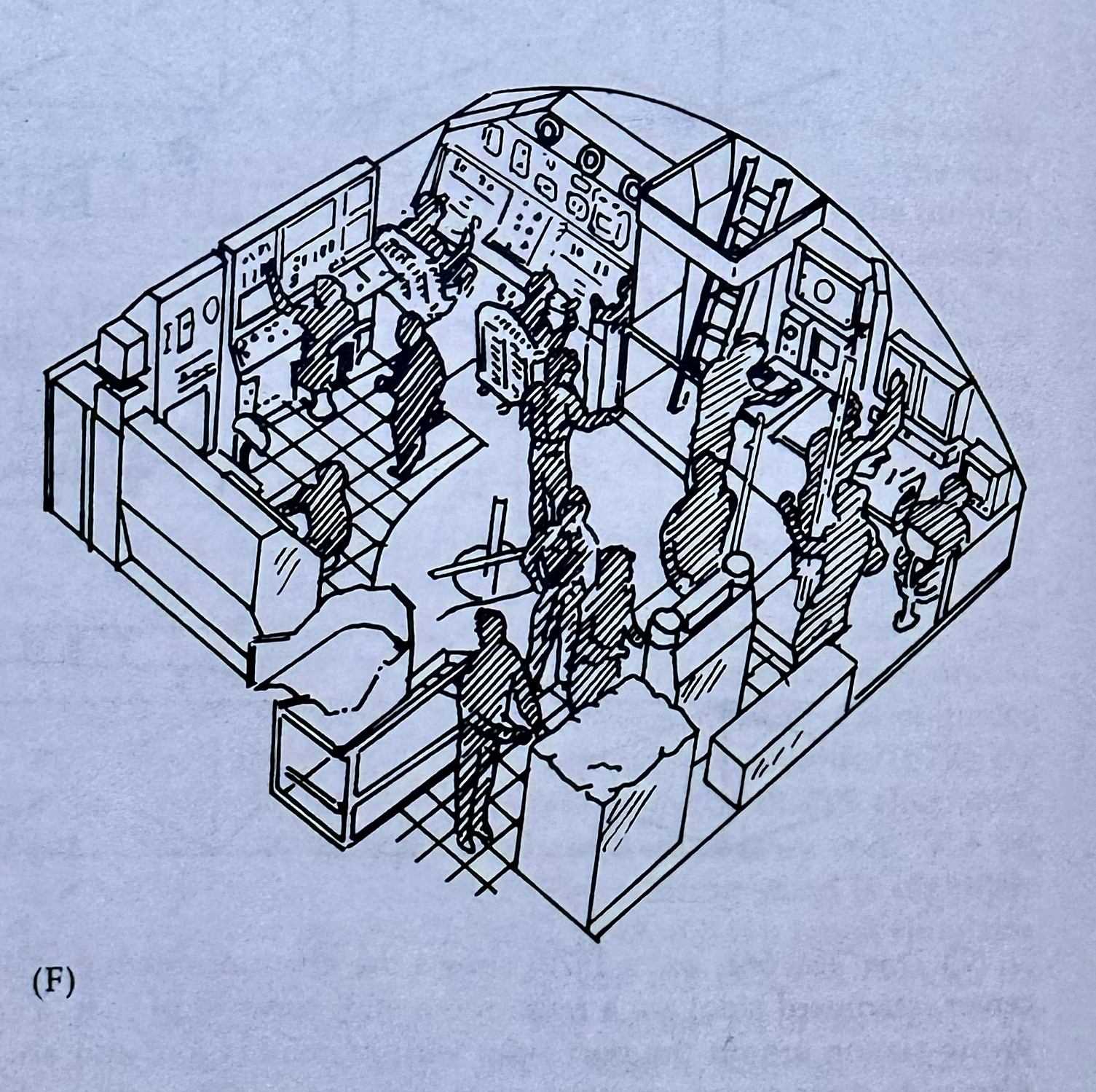

The control room is the nerve center of the submarine, and all operations are conducted from this space. During normal operations, there are eight men in this room. However, when at General Quarters (AKA battle stations), there could be 14 – 17 men in this room. This room is directly beneath the sail, and the layout vaguely resembles an inverted horseshoe when facing toward the bow.

The earlier Tang-class submarines were the first to eliminate the conning tower and move the fire control equipment down into the control room to create an attack center, but this made their control rooms more cramped. This was alleviated with the Barbel-class, which were arguably the first boats to introduce the more modern layout of control rooms.21

According to Tony Capitano, the basic positions in the control room are as follows:

- Officer of the Deck (OOD) (at the periscope stand)

- Chief of the Watch (ballast control panel)

- Helmsman (diving station, inboard seat)

- Planesman (diving station, outboard seat)

- (Diving Officer would be standing behind the diving station)

- Standby helmsman

- Quartermaster (navigator’s station)

- Interior Communications (IC) electrician

- Machinist Mate Auxiliary (MMA)

There are two periscopes in the center of the control room arranged in tandem. For whatever reason, the Navy removed both periscopes from the boat before turning it over to the museum, probably because they had sensitive ECM intercept equipment on them. So the veterans’ groups working to refurbish the submarine had to scrounge up two attack periscopes from somewhere.22 The forward one was the observation periscope. The Type 8 was a 36-foot periscope that was power-trained and had adaptors for the ECM equipment and ST radar on it. The head of this periscope is larger at about four inches in diameter. The AT-822/BLR is an omnidirectional communications intercept antenna operating in the 15 KHz – 265 MHz range. The AT-863/ULR is a microwave intercept antenna capable of receiving signals in the S or X-band range in the 1550 – 12,000 MHz range, allowing for rough direction finding. It would also have a Target Bearing Transmitter (TBT) on it. The rear periscope was the attack scope. This was a Type 2 periscope, which is 40 feet long, includes a stadimeter, and is manually trained. Smaller than the observation periscope, its head was physically smaller in profile (about one inch in diameter) to make it harder to detect when it is on the surface. There would also be an Ultra High Frequency/Identification Friend or Foe (UHF/IFF) antenna that is not visible on the outside. This antenna would be operating in the 200 – 500 MHz frequency range. Both periscopes have bearing transmitters for feeding information to fire control, sonar, and radar.

The periscope eyepieces also have mounting brackets to allow a camera to be mounted to them for taking photos through the periscopes. Rick Neault told me how he had to go to periscope photography school in Groton, CT, to learn how to use the camera. Since you cannot see what exactly the periscope is pointed at, you need to rely on the officer training the periscope to tell you when to hit the shutter release button. The film negatives would then be developed on the boat to determine if the photos came out well. Additionally, the observation periscope could tilt straight up, and a modified aeronautical sextant could be attached to the eyepiece to allow for star shots to be taken for celestial navigation.

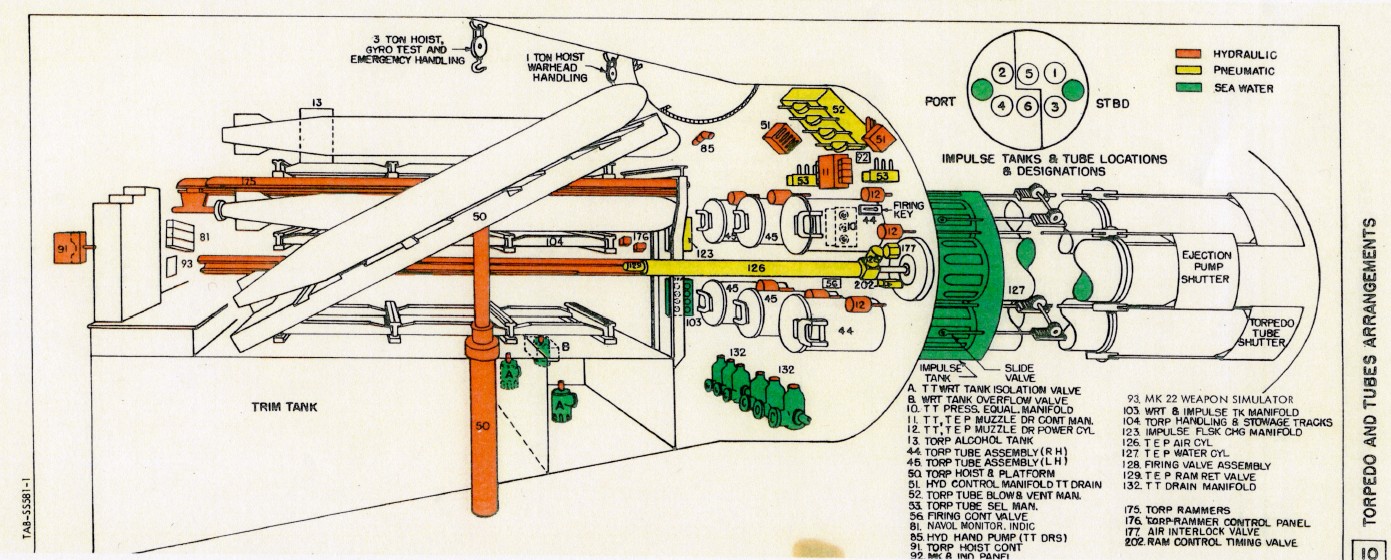

The consoles on the forward starboard side of the control room are the attack center. This is the Mark 101 mod 20 fire control system for the torpedoes. The Barbel-class were some of the first attack submarines to feature the modern layout of a control room. The size of the Mark 101 fire control system meant it could no longer fit inside the conning tower of a submarine. Since the Barbel-class subs have a sail and not a conning tower, this necessitated having a dedicated space within the control room for the fire control systems. The Mark 101 system also reflected the shift to sonar, rather than periscopes, becoming the primary sensor of a submarine.23

The Torpedo Data Computer (TDC) is an electro-mechanical analog computer. This thing is a bunch of gears, cams, shafts, and wires. It does one thing: calculate a trigonometric firing solution, taking into account the course and speed of our submarine, and the range, course, speed, and position of a target relative to our submarine, and then computing a firing solution for our torpedoes so they will intercept that target at a point and time in the future. This TDC is essentially the same thing used on WWII submarines, but there are upgrades and additional consoles in the attack center to allow for the control of the newer post-WWII torpedoes. While your PC or smartphone is basically 500,000 times more powerful than this thing, in 1959, this computer was state-of-the-art. Modern nuclear-powered submarines use all digital fire control computers, but do not make the mistake of thinking that just because the TDC is old, it is somehow primitive; it worked at the time, and it can still work today. Hence, the Navy still used it up through the 1980s. It is extremely accurate, reliable, and rugged.

The blue-lighted window on the TDC is the Mark 101 position keeper, which receives information from radar, sonar, or visual sources and plots the position of the target vessel in relation to our own. The information from the position keeper is fed into the Mark 18 angle solver, which is just aft of it. The angle solver computes a solution so that the torpedo will intercept the target. Wire-guided torpedoes can also be steered using the controls on the angle solver. Information from the angle solver is fed into the tone signal generator (just aft of it), which feeds the information from the TDC directly into the torpedo itself through a wire. Directly aft of the tone signal generator is the firing panel, which is used to select which torpedo tube is going to be fired and in what sequence. The torpedo would be fired from this panel, but at the same time, it would also be manually fired from the torpedo room in the event that there is a malfunction and the firing panel does not operate. The skinny console aft of the firing panel is a switchboard to select which sensor is feeding information into the TDC.

Unlike earlier systems, the Mark 101 used a pair of analyzers that could be fed up to three sets of data observations (one of which would be from passive sonar bearings). This made for quicker firing solutions in place of simply guessing. Unlike earlier TDCs, the Mark 101 could also account for the target making an evasive turn by allowing the operator to input a target’s tactical diameter.24

Forward of the attack center on the starboard side of the control room is one of the two chart tables. This would normally be the weapons officer’s station. It does the same thing as the navigator’s station but would be manned during battle stations when using torpedoes.

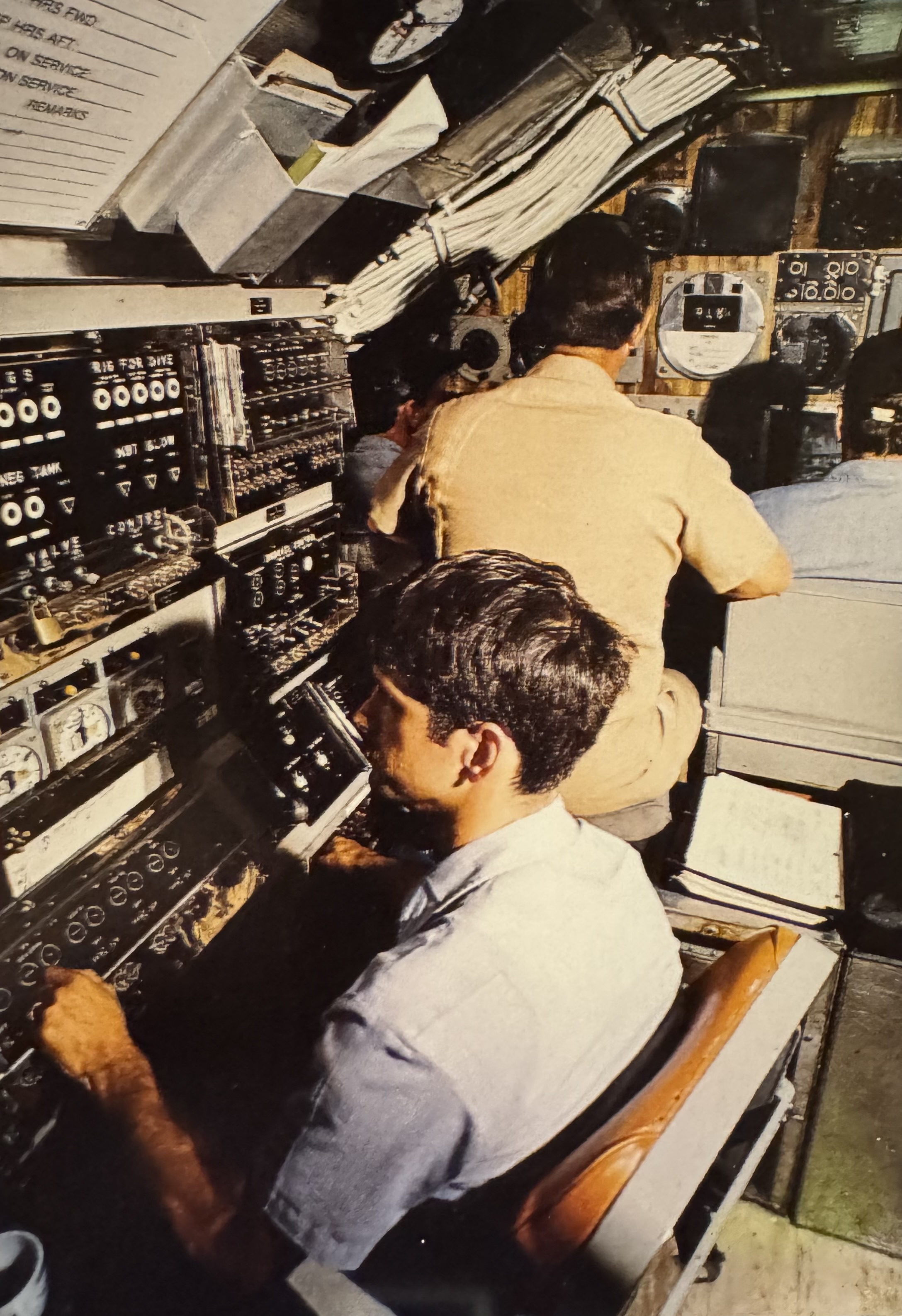

The two seats on the forward port side of the control room are the diving station. The inboard chair on the right is the helmsman/pilot’s seat. He controls the fairwater planes and rudder (i.e. the depth and direction of the sub). The outboard chair on the left is the planesman’s seat. He controls the stern planes (i.e. the angle of the sub).25 The gauges directly in front of their seats tell them the attitude of the submarine. Additional repeater gauges are on the bulkhead above them, which would be used by the diving officer, who would be standing behind them, and the conning officer/OOD. The selector switches on the panel between the helmsman and planesman’s gauges allow for either station to control any or all of the diving and steering functions (except emergency steering). Generally, junior enlisted sailors would be manning these controls because all they have to do is follow orders and steer the proper course. Just behind the two chairs of the diving station is the Mk. 27 magnetic gyrocompass. The orange-lit graph on the panel in front of the diving station is a bathythermograph. (Apparently, the exact same model is used on Los Angeles-class boats.) Water temperature is measured because a temperature gradient, known as a thermal layer or thermocline, can exist deeper down. Below this layer, the water is colder, and active sonar can bounce off it, allowing a submarine to hide below the thermocline.26

The board behind the diving station with all the green lights is the Ballast Control Panel. It is colloquially known as the “Christmas Tree,” due to its festive colors. Unlike older subs, the Barbel-class were the first to introduce push-button controls (rather: toggle switches) for the Ballast Control Panel.27 Divided up into several sections, in the center of the console are the indicators and switches for controlling the ballast tanks and vents. Green lines indicate closed, while red circles indicate open. A green/straight board would indicate that the boat’s openings are secure and rigged for diving. On the right side are the controls to raise and lower the masts (except the periscopes). Just beneath the mast controls are the hydraulic plant controls. Three hydraulic systems would be operating at all times, with another on standby. Beneath the Christmas Tree in the center are the controls for the trim system for the variable ballast tanks. On the left side are the gauges and controls for the air banks on the submarine.

Diving the Boat

Once the boat has crossed the 100-fathom line (600 feet of water beneath the keel), the captain or the Officer of the Deck would order the diving officer to submerge the ship. The diesel engines would be secured, all external hatches in the pressure hull would be closed, and the propulsion would be switched over to the batteries. Then the boat can dive. The Chief of the Watch, manning the Ballast Control Panel, would confirm that all hatches are secured and announce “green/straight board!” He would then announce over the 1MC “Dive, Dive!” and sound the dive alarm twice.28 He would then open the ballast tank vents, and 490 tons of seawater would flood in through the flood ports on the bottom of the boat, filling the ballast tanks between the outer hull and inner hull. The helmsman and planesman would push forward on their controls, providing a 6 – 8 degree down angle, and the submarine would go from the surface to underwater in about 58 seconds.29 Once getting below about 150 – 200 feet, it would be a very quiet and smooth ride. A diesel-electric submarine on battery power is actually quieter than a modern nuclear-powered submarine. Not to mention much cheaper. A modern nuclear-powered Virginia-class fast-attack submarine with all the bells and whistles costs upwards of $4 billion…with a B! Give or take a billion.

Once the boat had reached the ordered depth, the helmsman and planesman would level off their controls, and the Chief of the Watch would have to trim out the boat by pumping water through the trim system to add or pump out seawater, or shift it fore or aft to maintain neutral buoyancy and an even keel.

Surfacing the Boat

There are a couple of ways to surface the submarine. When the submarine is neutrally buoyant, then the boat can simply be driven to the surface by angling the planes. Another way is by either a low-pressure or high-pressure blow. A low-pressure blow uses 400 psi air and can also use the exhaust from the engines with about 15 lbs. of pressure to create positive buoyancy, and the engines would be used for the final trim of the boat. A high-pressure blow with the forward and aft main ballast tank blow switches uses 3,000 psi air to rapidly force the water out, and the sub will ascend to the surface quickly. According to the Ship Information Book, this submarine can store 588 cu. ft. of this high-pressure air in four banks (28 flasks) around the hull.

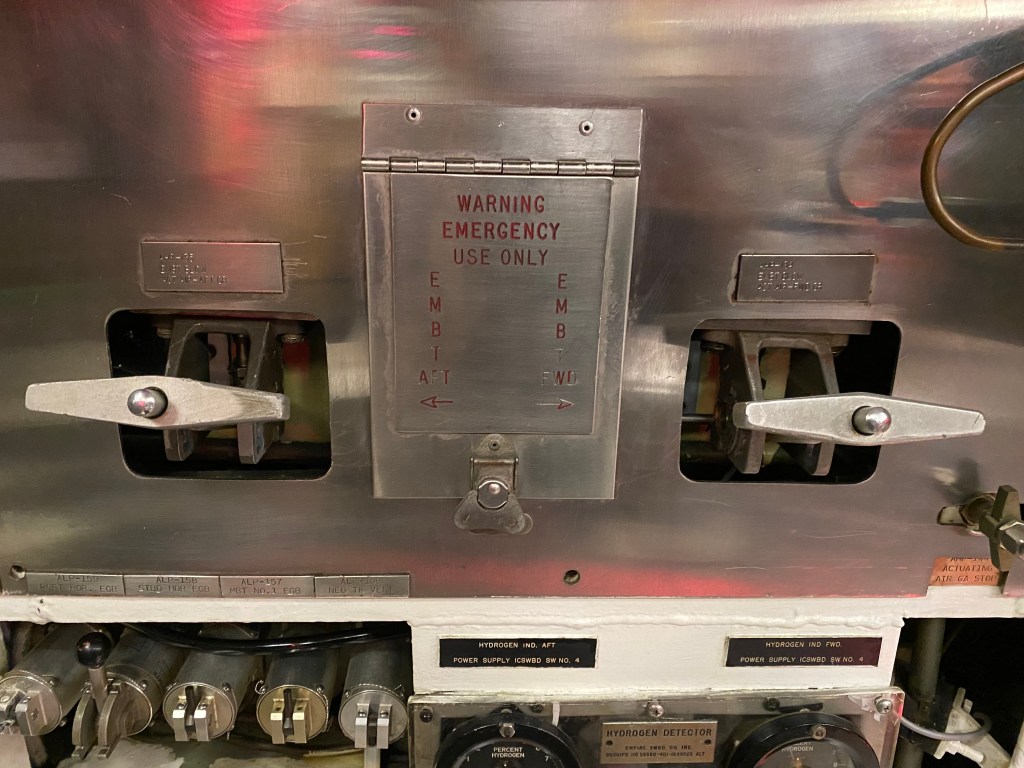

The last way to surface is via an Emergency Blow. Aft of the ballast control panel are the two switches for the Emergency Main Ballast Tank Blow. Also known as “chicken switches.” Upon activating these, 3,000 psi air would be blown into the ballast tanks, all the water would be rapidly evacuated, and the submarine would immediately rise to the surface. Submarines would practice this maneuver, but obviously, it is not the normal way to surface the boat. It is done in emergencies only…as in, if we do not get this submarine to the surface now, then we are never getting back up.30 Reportedly, the last time Blueback performed an emergency blow, she went from about 700 feet to the surface in approximately 58 seconds.

And no, your ears do not pop, and you do not need to worry about decompression sickness (AKA the bends) when submarines do this. The inner pressure hull is completely sealed and maintained at one atmosphere. You would just hold on to something. Depending on who you talk to, an emergency blow is either a terrifying event (if there is a genuine emergency) or the lamest roller coaster ride ever. It has also been described as a fast elevator ride that only goes up. One former Fire Control Technician on USS Haddock (SSN-621) said his boat would usually practice emergency blows about twice a year. Another who served on ballistic missile subs for 12 years said he only did this twice in his entire career.

Blueback DID NOT perform the famous emergency blow scene near the end of the film, The Hunt for Red October, as some people erroneously claim. That was actually USS Houston (SSN-713). According to a sonar technician on one of my tours who was aboard USS Houston when she performed that stunt, this shot required numerous takes, and they spent most of the day going deep and then doing emergency blows over and over. This is because the camera helicopter did not know exactly where the sub would surface, so it took multiple tries to get the shot you see in the film. Ultimately, it got kind of boring. One of the shots, possibly the last one, resulted in the fiberglass dome on the bow that covers the sonar array cracking when the bow came down after breaching the surface. This ultimately resulted in the film company paying the Navy $5 million to get the fiberglass dome fixed or replaced.

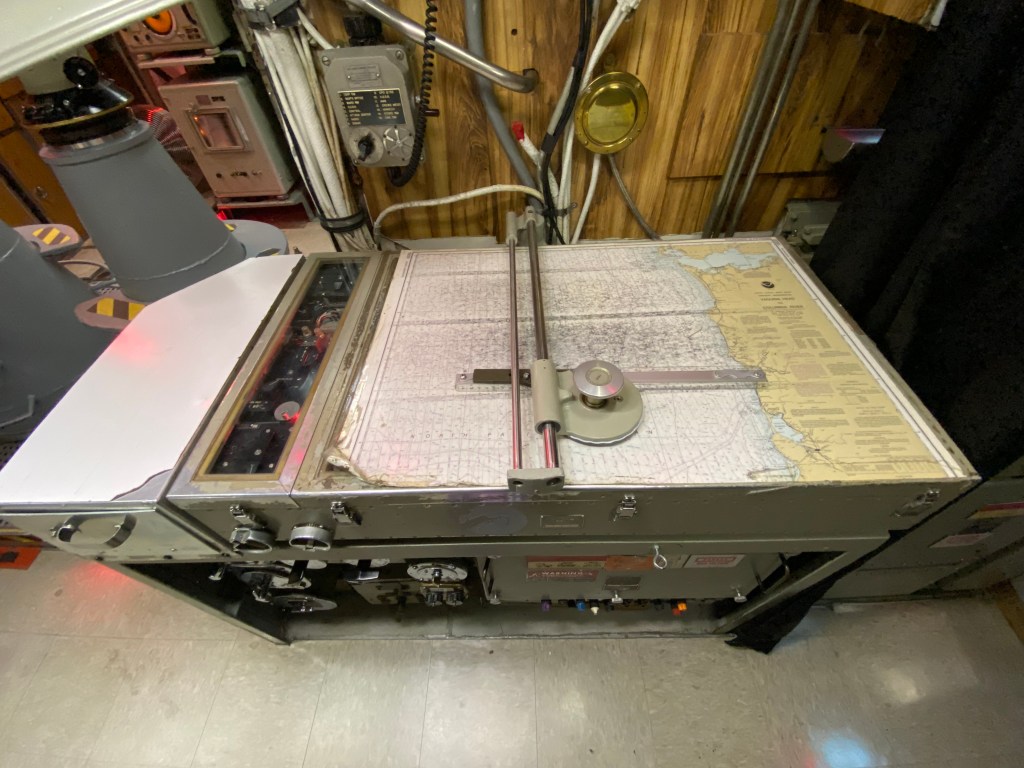

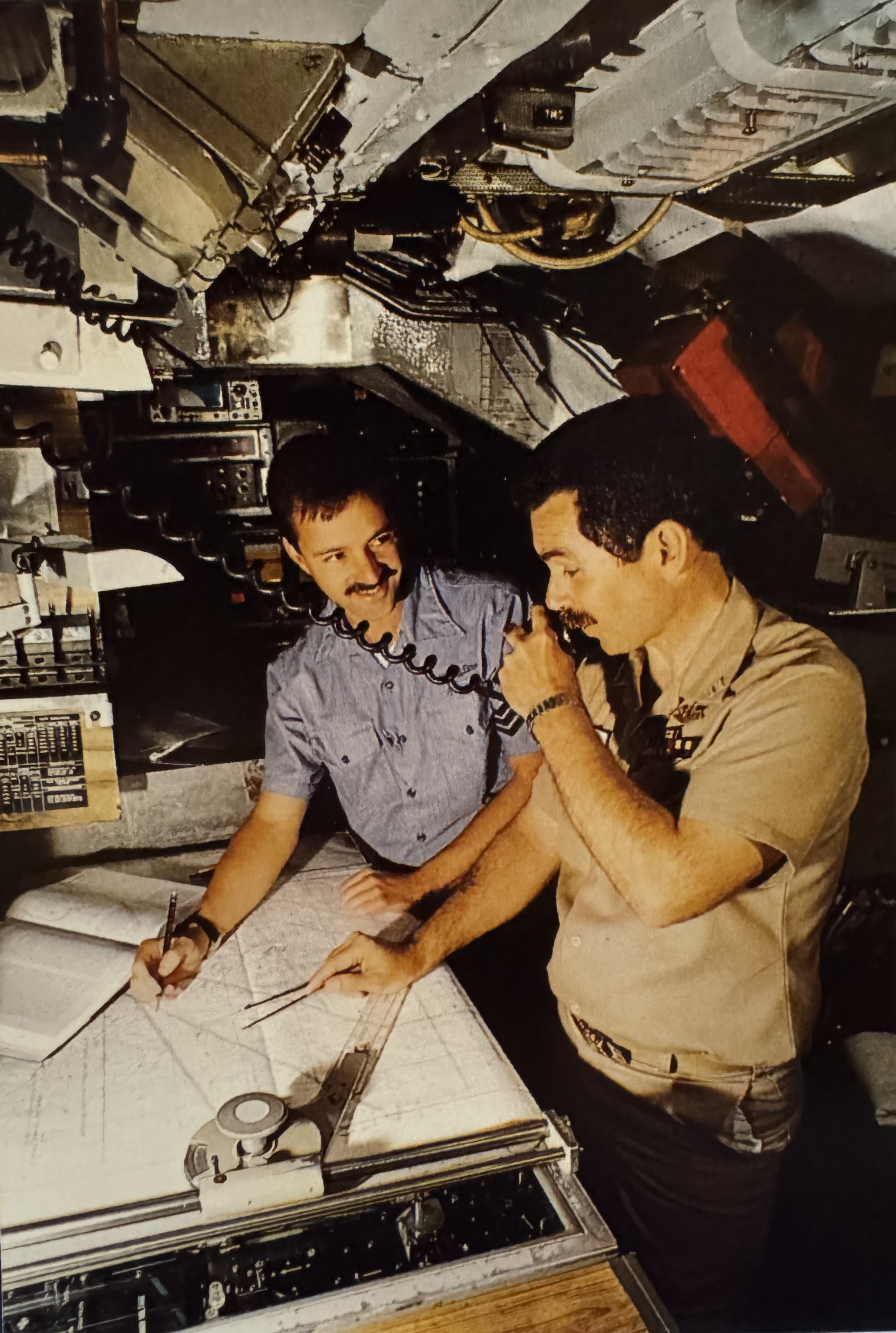

Just opposite the chicken switches, and abaft the periscopes, is a chart table. This is the navigator’s station. The Quartermaster of the Watch would be here, and this is where the submarine’s course is normally plotted. A positional fix could be taken either on the surface or when submerged down to about 60 feet with the radio masts extended. Once their position is calculated, that information, along with information from the gyrocompass, could be inputted into the dead reckoning tracker on the plotting table. There was no internet connection and no Google Maps or anything like that for the sub. Instead, they would rely on traditional paper charts of the ocean, celestial navigation with a sextant, and terrestrial-based radio navigation (like LORAN). However, Blueback did have satellite navigation near the end of her career (Transit AKA NAVSAT).31 Upon successfully getting a fix on their position, they could input that information into the Dead Reckoning Tracker on the plotting table. Under the plotting table is a small light that shines upward and shows the rough position of the submarine.

Navigational errors are to be expected, and positions are not absolute. It depends on the method used. Modern GPS (like on your smartphone) gives a very accurate fix of your position to within a few feet, but submarines like Blueback had earlier satellite navigation late in their service. Former U.S. Navy Quartermaster, Blueback crewman, and tour guide, Rick Neault, told me that a satellite navigational fix on Blueback was accurate to roughly 50 feet, and he rarely used LORAN-C because it was so unreliable.32 A radio navigation fix could expect errors of several hundred feet to several hundred yards. A celestial navigation fix using only the sun or stars could be off by several miles or more.

The area in the very back of the control room on the port side contains the radar scope and Electronic Support Measures/Countermeasures (ESM/ECM) equipment. This would be used for intercepting, locating, classifying, and identifying signals (radar, radio, etc.). According to the boat’s documentation, the ESM suite includes the WLR-1 and WLR-3 receiving sets and the BLR-6 microwave intercept receiver.

The WLR-1 set is a high-resolution, high-sensitivity, superheterodyne receiving system used for analyzing radio and radar signals in a range of 50 – 10,750 MHz. It has a 37-second sweep and a long persistence scope, allowing for a good probability of intercept. The system makes use of nine RF tuners, which break the frequency spectrum down into nine bands. By prepositioning one of the nine RF tuners to a given frequency, it can store from 1 – 10 signals.

The WLR-3 is a countermeasures receiving set using a wide-band, crystal video receiver. It can be used in conjunction with the WLR-1 and monitor other bands of frequencies while the WLR-1 scans a single band or analyzes a specific contact. Using the BLR antenna, the WLR-3 set operates in two bands: 2,300 – 5,200 MHz and 4,800 – 11,000 MHz. It can give a rough frequency, bearing, and pulse repetition rate.

The BLR-6 microwave intercept receiver uses the AT/863/ULR spiral antenna in the Type 8 periscope to provide wide band coverage in the ranges of 2,000 – 4,500 MHz or 8,000 – 11,000 MHz or both. It provides signal parameters to give a rough bearing, S or X band, and pulse repetition rate. This information can be fed to the WLR-1 for additional analysis.

The following antennas can be used with the ESM suite:

| Antenna | Frequency | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| AS-1071/BLR | 2,300 – 10,750 MHz (Bands 7 – 9) | Direction Finding Low side 2300 – 5200 MHz High side 4800 – 10,750 MHz |

| AS-962/BLR | 1,000 – 2600 MHz (Band 6) | Direction Finding |

| AS-994/BLR | 550 – 1,100 MHz (Band 5) | Direction Finding |

| AS-371/BLR (Door Knob) | 1,000 – 4,000 MHz (Bands 6, 7) | Omnidirectional |

| AS-693/BLR (Dipole) | 30 – 1,000 MHz (Bands 1 – 5) | Omnidirectional |

The frequency spectrum would be broken down into the following nine bands:

| Band | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 1 | 50 – 100 MHz |

| 2 | 90 – 180 MHz |

| 3 | 160 – 320 MHz |

| 4 | 300 – 600 MHz |

| 5 | 550 – 1,100 MHz |

| 6 | 1,000 – 2,600 MHz |

| 7 | 2,300 – 4,450 MHz |

| 8 | 4,300 – 7,350 MHz |

| 9 | 7,050 – 10,750 MHz |

In a normal search plan, the ECM operator would use the WLR-3 for bands 7 – 9 and the WLR-1 for bands 1 – 6, with occasional sweeps through bands 7 – 9. When a signal is detected on the WLR-3, it is determined if it is on the low band (2,300 – 5,200) or high band (4,800 – 11,000), or both (4,800 – 5,200), and then analyzed using the WLR-1. While at periscope depth, the BLR-6 on the periscope can be used to detect signals in the S or X bands, while the WLR-1 would search bands 1 – 3. If no contacts are obtained, the BLR mast would be further raised, and the WLR-3 would search bands 7 – 9. If still no contacts were obtained, the BLR mast would be fully raised, and the WLR-1 would sweep all nine bands. If a contact was detected on the BLR-6 antenna, but it was undesirable to raise the BLR mast, then the information would be fed to the WLR-1 to determine the pulse repetition rate.

Most of Blueback‘s career was used for intelligence gathering, and many of her operations regarding that are still classified. We have met several officers and about 6 of the captains, but they are still tight-lipped about the details of her operations. She did three patrols off the coast of Vietnam and patrolled off the coast of northern Russia. One tour guide told me that the largest number of men on board this submarine during one patrol was around 130. In addition to the 85 crew, there were teams of Navy SEALs, Recon Marines, and a group from the CIA. The sub was operating off the coast of Russia… and by off the coast, we mean inside Vladivostok harbor.

The red lighting (known as “rigged for red”) serves a few purposes. Firstly, it tells the crew that it is nighttime. Windows and sunshine are non-existent on a submarine, so the natural day and night cycle has no meaning. Secondly, if the sub is at periscope depth with the periscopes raised, then red light will not compromise your night vision as much as white light. Thirdly, white light can travel up the periscopes and be seen for miles at sea, especially in the dark. Red light is harder to see at night due to its longer wavelength, and the rods in your eyes are much less sensitive to red light. If the submarine is operating in a highly sensitive patrol area, then the lights in the control room can all be blacked out.

Sonar Room

At the bottom of the ladder from the control room is the sonar room. Tours normally just pass by it coming down the ladder, since you would be hard-pressed to fit sixteen people in this room, and we definitely do not want people touching the panels and equipment in there. Indeed, some of the equipment is still energized and operational.

The current equipment contained in this room is as follows:

- AN/BQR-2B – passive sonar

- AN/SQS-49 (BQS-4) – active/passive sonar

- BQG-2B – sonar receiver

- BQA-8B – sonar computer (measuring own ship’s noise, cavitation, and figures of merit)

- RD-337/UNQ-7E – sound recorder

- RQ-55209 – cavitation indicator

- IP-334/BQR-2B – azimuth indicator set for BQR-2B sonar set

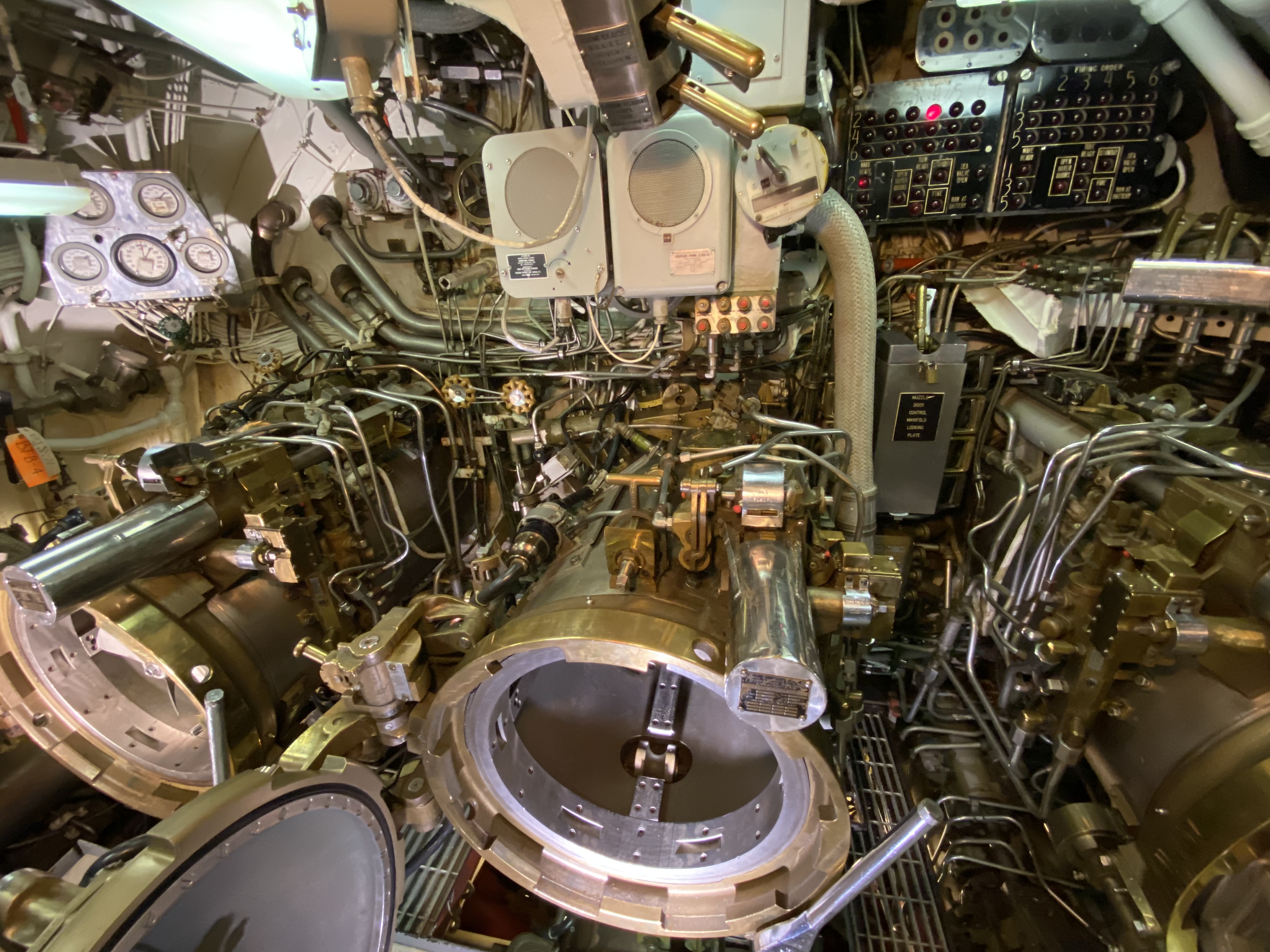

The sonar arrays are in the bow of the submarine, with the SQS-49 array located above the torpedo tubes and the BQR-2 array below the tubes.33 The arrays are covered in sound-transparent glass-reinforced plastic. Both the BQR-2 and BQS-4 sonars are mounted on other submarine classes, as well. Such as the earlier Tang-class.34

BQR-2 Passive Sonar

The BQR-2 is the passive sonar listening array for medium-range detection and fire control tracking. Essentially, it is an American copy of the GHG sonar taken from captured German Type XXI U-boats; the most advanced passive sonar of its time for post-WWII submarines (circa 1956).35 It can operate in either searchlight or scanning mode and includes forty-eight 3-foot vertical elements in a 6-foot diameter circle and a 5-foot high dome. It has an 18-degree beam, operating between 500 cycles and 15 kHz. While the German GHG was used like a searchlight (i.e. with the beam turned in a certain direction to listen), the U.S. BQR-2 added a commutator operating in the 5 – 9 kHz range, which either scanned continuously at 4 RPMs or was tracked by the Bearing Direction Indicator (BDI). The BQR-2B version added a second commutator operating in the 700 Hz to 1.4 kHz range that fed a Bearing-Time Recorder (BTR). A piece of paper rolls down past a stylus that moves horizontally, with each pass of the stylus being one full commutator scan. Whenever the received signal reached a certain level, the stylus placed a mark on the paper. Over time, the BTR could be used to estimate a target’s motion and position. The BTR beam could be driven at 1 or 10 RPMs, with the higher one being used for a stronger target signal.36 The BQR-2B has a sound-bearing recorder for 1 – 4 kHz, but it can aurally detect noise at 0.3 – 15 kHz. Automatic target following had an accuracy of 0.25 degrees against a noisy submarine at 12,000 yards. The typical performance for this set is as follows:37

| Noise of submarine | Detection distance above thermocline | Detection distance below thermocline |

|---|---|---|

| (Own sub) Quiet (Target) Snorkeling/cavitating | 110,000 yards | 8,000 yards |

| (Own sub) 13 knots (Target) Quiet/shallow | 13,000 yards | 4,000 yards |

| (Own sub) Quiet (Target) Quiet/shallow | 10,000 yards | 2,500 yards |

That said, in May 1951, Captain W.B. Siglaff of SubDevGru 2 reported that the best range of a BQR-2 passive sonar was 20,000 to 30,000 yards. The worst range was 2,000 to 4,000 yards, and the average was 8,000 yards.38 The documentation on Blueback similarly credits the BQR-2B with a detection range of 40,000 yards in excellent sound conditions with a bearing accuracy of 0.1 degrees. It has a 50% probability of detecting a snorkeling submarine traveling at 10 knots at a range of 36,000 yards in a sea state of 2 with a thermal layer at 100 feet depth. Echo ranging in the 1 – 15 kHz range can be tracked. The passive sonar can be used as an input for fire control.

The desktop computer in here is a modern addition and would not have been there when the submarine was in service.39 The screen shows a fake digital waterfall display. Since this submarine was originally in operation before digital computers, Target Motion Analysis (TMA) was done via a Bearing Time Recorder (BTR) as seen above the BQR-2B sonar console. There is also an azimuth indicator and a BTR console up in the control room. A modern submarine’s digital waterfall display originated from this analog device.40

SQS-49 (BQS-4) Active Sonar

SQS-49 sonar is an SQS-4 mod 1 with MARK (Maintenance and Reliability Kit). The SQS-4 is the first postwar long-range sonar produced for both surface ships and submarines. Effectively, it is a lower-frequency version of a WWII QHB, the first operational U.S. scanning sonar, with a similar beam shape and three different pulse lengths: 6 ms (50 kW), 30 ms (30 kW), and 80 ms (10 kW) at the original frequency of 14 kHz. The Mod 1 decreases the frequency to 8 kHz. SQS-4 is considered accurate out to 5,000 yards on surface ship sets and can achieve even longer ranges on submarine sets. It can be operated in a passive mode and incorporates functions of both a search and attack sonar, such as both a ship-centered (PPI) and target-centered display.41 On a noisy, transiting submarine, SQS-4 has a range of around 6,000 yards.42

Documentation on the sub notes that this active ranging sonar also has the capability of passive listening. It has a range of 15,000 yards in active mode with a range accuracy of 2% of scale and bearing accuracy of 1 degree (3 degrees in passive mode). While this set is normally used in passive mode, if an ASW vessel has contact, then a maximum intensity signal can be emitted to saturate the vessel’s scope and present a false target. It has a peak power output of 50 kW.

Many BQR-2B sets are often combined with BQS-4 active sonar sets since the passive array can be used as a receiver for an active set. The BQS-4 features seven transducers stacked on a stave inside the BQR-2 array, pinging at 7 kHz.43

BQG-2B Sonar Receiver

Originally, the Passive Underwater Fire Control Feasibility Study (PUFFS), this set is for determining the passive ranging and bearings of a target. Norman Friedman writes that the BQG-1, -2, and -4 sets obtained information from a set of three hydrophones. The original idea was that three equally spaced hydrophones on a 250-foot base, operating at 0.2 – 8 kHz, would be able to obtain ranges within 2 percent against a snorkeling submarine at 10,000 – 15,000 yards. They would measure the curvature of the wavefront of the target signal, compare the time of arrival at the three detectors, and then correlate the information. Feasibility studies of this began in March 1953 and progressed to a working model aboard USS Blenny (SS/AGSS-324) in November 1960.44 Other publications suggest that the Barbel-class submarines never had the PUFFS system installed, or at least the hydrophones, since they would have created too much hydrodynamic drag.45

Documentation on the boat suggests that this was originally a BQG-2A receiver with passive ranging and bearing accurate to within 20,000 yards (+/- 25 yards range and +/- 0.1 degrees of bearing) and bearings accurate to 40,000 yards. However, it was ineffective against echo ranging in frequencies below 5.6 kHz. The set could track two targets simultaneously (port or starboard) and input information to fire control.

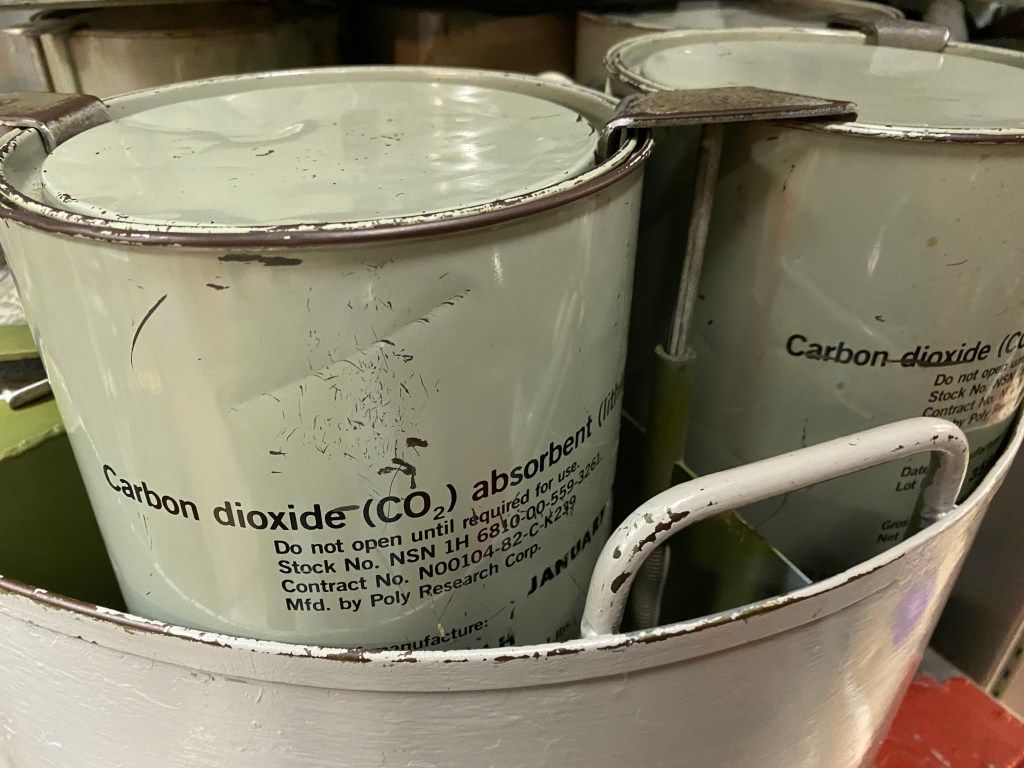

Silent Running

Documentation on the boat for operations notes that three conditions of silent running are prescribed by the ship’s organization manual.

- Patrol Quiet: Equipment is secured to the maximum extent possible with normal living conditions. This would be when the submarine is operating in its patrol area. The AC load is dropped so it can be maintained by one 75 KVA generator set.

- Battle Quiet: Maximum securing of equipment and only personnel on watch are up and about. Self-noise is reduced so that a Mk. 37 torpedo’s gyro can be heard to turn up over the UQC Underwater Communications Set.

- Sonar Quiet: Extreme quieting conditions are maintained for the purpose of specialized sonar recording. Only equipment essential to safely operate the ship is used under this condition.

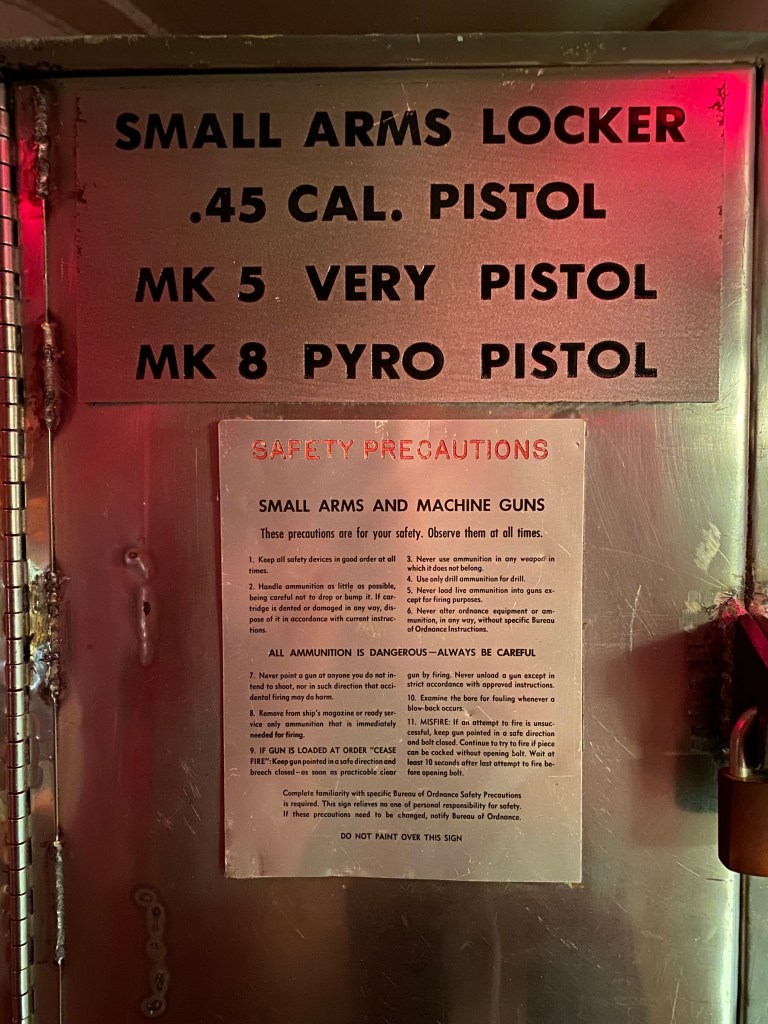

Small Arms Locker

Forward of the sonar room are two metal cabinets which are the small arms lockers. Small arms are handheld weapons like pistols, rifles, shotguns, etc.

In the top small arms locker of Blueback would be pistols such as M1911s, as well as pyro and very pistols (AKA flare guns). The bottom locker is larger and would hold M14 rifles and 12 gauge shotguns.

NAVORD OD 10718, originally published in June 1956 and declassified in August 2025, shows the original ordnance loadout for a Barbel-class submarine. When commissioned in 1959, the small arms lockers would have included 8x Colt M1911A1 .45 caliber pistols, 6x Thompson .45 caliber submachine guns, 3x M1 30.06 M1 Garand rifles, 2x Mk. 5 Very pistols, and 2x Mk. 8 Pyrotechnic pistols. The upper locker has 14 pegs for pistols, suggesting that when Blueback was armed with the nuclear-tipped Mark 45 torpedo, the number of pistols would have been increased. There would have also been a line-throwing gun. As time went on, the small arms in these lockers no doubt changed to more modern weapons like M14 rifles and 12-gauge shotguns.

All naval vessels have small arms to defend the ship, and submarines are no exception. However, unlike the movies, you are unlikely to be repelling boarders, and if you get into a gunfight on a submarine, then something has gone very wrong. Additionally, the base skillset of sailors is seamanship, not infantry tactics. Sailors are not trained to run around in jungles or up and down mountains blasting away with rifles, machine guns, and rocket launchers. That is what we pay the infantry (Army 11Bs and 0311 Marines) for.

Rather, the small arms are used when the submarine is in port. A sentry (such as the Officer of the Deck) will be stationed on the pier or the quarterdeck with a weapon to provide security and prevent unauthorized people from getting on the boat. People do not walk around a naval vessel (or any military installation) carrying weapons at all times. There is simply no need for that. The people who would be armed are MPs or MAs (Military Police/Master at Arms). The small arms would always be in a secure area, and if there is ever a need for them, then there would be time to unlock them and issue the weapons out. Certain secure areas of a vessel, such as the engineering spaces or the radio shack, would likely have someone with a loaded weapon present to deter intruders. Do not try to enter these areas without authorization, or you will be greeted with a loaded pistol pointed in your face and told in no uncertain terms to leave.

There could also be small arms qualification where the submarine could be on a surface and the sailors would be topside on deck (or on the bridge on the sail), firing at targets to maintain their qualification in using pistols or rifles. A swim call would also necessitate someone standing on deck with a loaded weapon in case any sharks show up to the party.

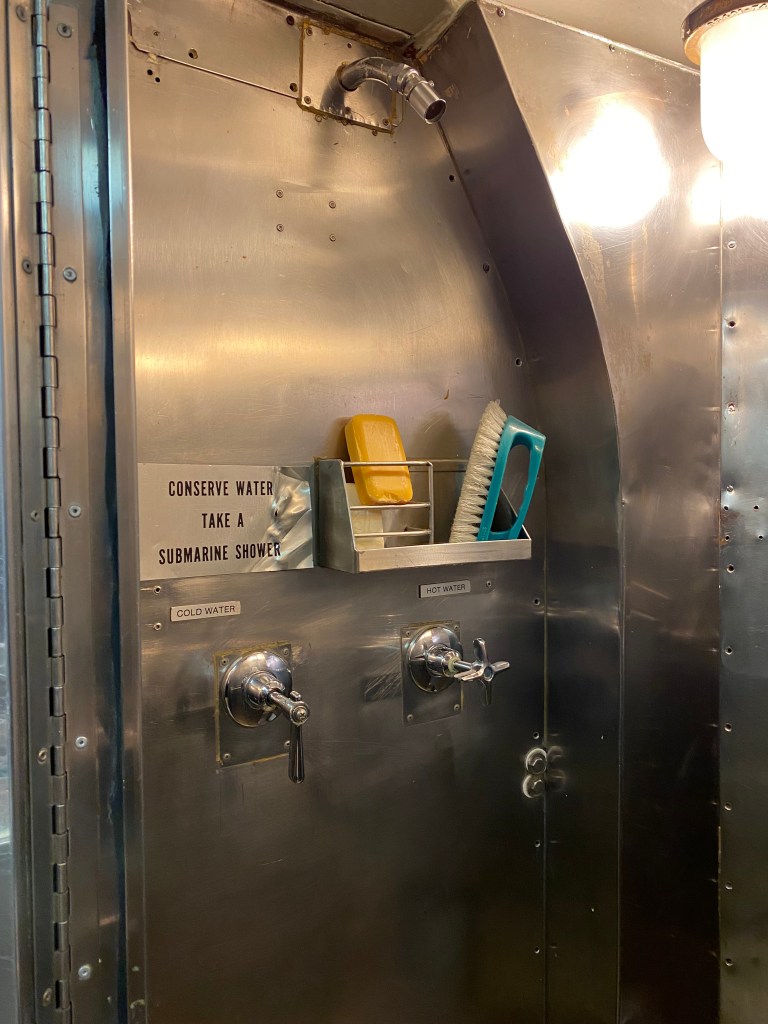

Showers & Heads

There is nothing particularly special about the showers and heads (toilets). There are two showers and four heads for the 77 enlisted crewmen.46 I have already written a short article on the procedure for using the head (as well as one for the showers). The showers are an interesting experience because a diesel-electric submarine would be perpetually rationing freshwater. Any shower you take would not be a long “Hollywood” shower, as sailors call it, because it wastes too much water. Rather, the experience is a one or two-minute-long “submarine” shower (if the sub is operating at high latitudes, then you can bet the water would be freezing). Here is how you take a submarine shower:

- Get in the shower.

- Turn the water on for 10 seconds and get wet. Turn the water off.

- Apply your shampoo and soap. Scrub.

- Turn the water back on for about 30 to 45 seconds and rinse off. Turn the water off.

- Get out and dry off.

If you are lucky, you will get a shower once a week on this submarine. More than likely, you will shower once every two to three weeks or even just once a month. According to Rick Neault, on one patrol, the crew went roughly 54 days (almost 8 weeks) before they got a shower. Rick also said that the water heaters worked, so at least the showers were hot/warm, but if the submarine was in port and receiving water from ashore, then they would be cold. Still, he said he could count the number of showers he took on these boats (Bonefish and Blueback) on both hands. Usually, showers were just once a month.