Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the presenter’s own and do not necessarily reflect the official policies or positions of either the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), the United States Navy, or the United States Government. While strong efforts are made to ensure accuracy, all information is subject to change without notice. All personal statements, opinions, omissions, and errors are the commentators’ own.

More information about the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), as well as USS Blueback, can be found on the museum’s website at omsi.edu. OMSI is a non-profit organization that receives support from various sources, including generous donations from people like you.

Here’s another interview from a Blueback volunteer tour guide and former Barbel-class sailor.

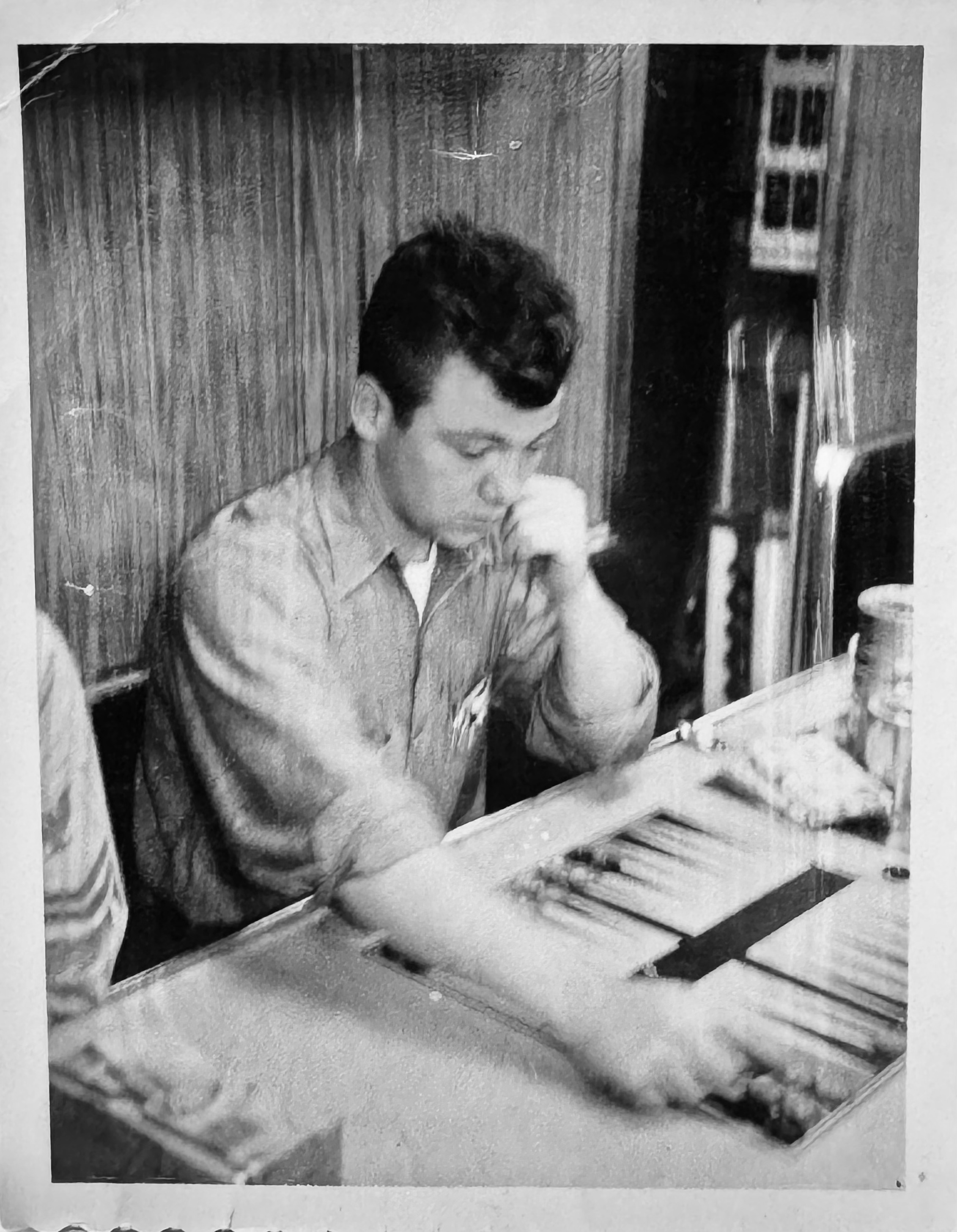

Featured Tour Guide – Tony Capitano – IC2/MT2, U.S. Navy

Our featured (volunteer) tour guide in this post is Tony Capitano. Tony served in the U.S. Navy as an Internal Communications Electrician, 2nd class (IC2), and later as a Missile Technician, 2nd class (MT2). His time in the Navy included duty aboard the submarines USS Barbel (SS-580), USS Cusk (SS/SSG/AGSS-348), and USS Lewis and Clark (SSBN-644) (AKA USS Lost and Confused, as he calls it). He joined OMSI and the Blueback as a tour guide in 2008.

Tony is unique, being one of two tour guides to have served on one of the three Barbel-class subs. The other is Rick Neault, who served on Bonefish and Blueback. (See Rick’s interview about the Bonefish fire.) Tony’s technical knowledge of the submarine surpasses all of us. Always one for conversation, Tony’s plethora of stories is enhanced by his pleasant demeanor and fun attitude. As an aside, his last name actually means captain in Italian. Had he been an officer and risen to the rank of Captain, then it would be the ultimate redundancy. “This is the skipper, Captain Captitano.” (i.e. Captain Captain.)

Transcript

Tim:

Hello everyone, welcome back. I have a very special guest for you today, one of our other Barbel-class sailors apart from Rick Neault. I’m here with Tony Capitano, a submarine veteran, and we’re just going to ask him a little bit about his time in the Navy and what it was like being on submarines. So welcome, Tony.

Tony:

Hi!

Tim:

Could you tell us where you’re from and why you joined the Navy?

Tony:

Oh cool. Well, I was born in Buffalo, New York, but I moved to Tennessee in grade school, so I don’t know where I come from. Anyway, why did I join the Navy? Well, I think I watched a lot of Victory at Sea movies when I was a kid, and submarines were kind of cool, and I thought, well, that’d be fun. And my brother joined the Navy, too. He was in the Navy before me. He was on an oiler, though. That didn’t seem like a real fun job to me, so.

Running around throwing lines across to another ship, and filling them up didn’t sound like a good job. I joined the Navy in 1960. I went to San Diego for boot camp. I went to A school in San Diego as well, IC “A” school. Then I went to sub school right after that.

My sub school lasted a little longer because I ended up, first thing back then, the first thing you did was do the tank test, and if you didn’t pass the tank test, you didn’t go to sub school. Well, I ruptured my eardrums, so I had to wait another six weeks before they let me do it again. So I took a little longer at sub school than normal, and then I reported aboard the Barbel.

The Barbel was in the shipyard in Kittery, Maine. She just finished doing an overhaul. Well, I reported aboard in June, I believe, and we didn’t leave until December because everything five inches and above was torn out and rebuilt because she took 350 tons of water in the engine room on a deep dive. So they overhauled her and moved the bow planes to the sail at the same time. So we spent a lot of time in the yard.

We did some training during the yard, but most of the lines and stuff were torn out. So I ended up mess cooking once we got underway, and our first home port was Norfolk, Virginia. So we were in Norfolk for Christmas, and I was telling you the other day, one of the electricians got a Christmas card from Yokosuka, Japan, saying, “See you next year.” And next year we were in Yokosuka, Japan, so that’s kind of interesting.

We went through the [Panama] Canal, spent about a month and a half in the Caribbean, hitting a few islands and stuff, and went through the canal. We were supposed to stop in Acapulco, but one of the enginemen got hepatitis, so they wouldn’t let us in. This was back when they didn’t have any shots for hepatitis. So they air-dropped a bunch of stuff to us, and the corpsman gave us all a shot.

But we got to stop in a little town above Acapulco called Manzanilla, which was kind of fun because it was a little bitty town, and it had just this oil dock that was there, so it wasn’t a major docking system. But they had a wedding, so they invited us to the wedding. The whole town was involved in the wedding, so it was kind of fun. We had an open house for the sub, so we had people coming down the main hatch, going out the torpedo room hatch. So it was kind of interesting.

Then we were stationed in San Diego for a period of time, did ops out of San Diego, went to the Seattle World’s Fair, and then got stationed in Hawaii. So we went from Norfolk to San Diego to Hawaii.

Did a couple tours – WESTPAC tours. I ended up getting transferred to the Cusk after that because I signed up to change my rate to missile man, and they were getting ready to go to WESTPAC again, so the XO said, “Well, I’m not going to take you with me because I don’t want to transfer you in Yokosuka or someplace.” So he said, “You got a choice. You either spend three months or so up in the sub barracks,” because at the time in Hawaii, we actually had barracks that we stayed in, so we had lockers for our clothes and stuff. So he said, “You could either go up there and be a Master at Arms or the Cusk,” which is a Balao-class submarine, was going to Tahiti, and they needed an IC electrician. So I went to Tahiti for three months. Then went to school. So I just spent a TAD (Temporary Assignment to Duty) to them.

I should say I started out as a fireman, E3, IC striker, and I left as an E5 IC man. I qualified on all electrical watches on the Barbel. I qualified as an IC electrician, roving watch, senior controllerman, junior controllerman. So I stood all the electrical watches.

I think the main reason they wanted to do that, the electrician in my duty section did not want to stand battery watches during the in-port. So he made sure I was qualified to do the battery charges in-port. Well, it’s a four or five-hour watch, so depending on how bad the battery is. So he didn’t want to do it. He’d just as soon stand a watch as a below-decks guy instead of standing a watch in the back.

Tim:

Perhaps for our listeners, could you explain what an IC electrician does?

Tony:

An IC electrician. Well, IC electricians take care of – on this class of submarine, it was kind of nice because everything on the submarine, one end of the switch was mine, and the other end of the switch was mine. So all the servo synchro, all the servo valves, all that stuff is something I had to work on. So it was a nice submarine because everything in the submarine had a part of electrical connection to it. So all those switches on the control panel, the other end of it, and that switch is my problem. Plus, we took care of all the navigation equipment, the gyros, the dead reckoning analyzers, the plotters, all the plotters. All the sound-powered phones, yeah, sound-powered phones, that’s another project.

For instance, all the external cabling I ended up working on. So the masts, all the masts have cables in there. I remember being in Yokosuka underneath the sail patching a cable with a, we had this plastic device that you would trim the insulation off and put this plastic device on, fill it up with epoxy, and close it up and seal it. So those are the kind of things that we would be doing.

Tony said some of the areas inside the sail can be accessed via the bridge access trunk at the forward end of the sail, but otherwise, he would crawl into the sail from below it via the turtleback superstructure.

Tim:

I see. And you recounted a story to me earlier. Could you tell the one about that sailor where you pressurized the boat and he opened up the hatch to the sail and ended up flying out of it?

Tony:

Right. Yeah, we were on our way to Seattle, and we stopped in San Francisco, and they decided to put a five-pound pressure test on the main compartment, so the living compartment, which is the largest compartment on the ship. It’s about 22,000 cubic feet or something like that. I’m not, don’t remember exactly. But anyway, they put a five-pound pressure on and then you hold it for, I don’t know, 15 minutes or something to make sure there’s no leaks. And then you start bleeding it off. Well, it takes time to bleed that much air off. And he went up to the hatch and thinking that it was at a level where he could crack the hatch. And when he cracked the hatch, the hatch just opened, flew open, and he ejected himself. Unfortunately, he did never come back to the submarine. I think he was in the hospital for a long time. Severe head injuries because there’s an I beam above that hatch. So I think he took a direct hit on that.

Tim:

Ouch. Alright, well, I believe eventually you transferred to a boomer, right?

Tony:

Yes, I ended up going to missile school. We went to an A school and a C school. So it was 57 weeks of school. So then I got transferred to the Lewis and Clark, which was a new construction boat. I picked it up in Newport News, Virginia. And so I spent the end of my career on that. We went on several, you know, we went on several cruises, which were kind of fun. So being a missile man is totally different than being an IC man, but it was a nice job. I enjoyed it.

Tim:

So, how was the transition from being on an attack submarine to being on a ballistic missile submarine? Did it require you to re-qualify and -?

Tony:

Oh, yeah. You got to re-qualify. Well, if I had stayed longer on the Cusk, I would have had to re-qualify on it. But I was only there three months. And so re-qualifying wasn’t going to happen because it is a totally different class of submarine than the Barbel. So I would have had to re-qualify on it. So yeah, I re-qualified on that. We went through the entire sub, nukes, and everything. So that was fun. It’s kind of different. You know, like on a diesel boat, you basically, once you qualify, you keep going through the boat because you’re the below-decks watch. So in port, you’re constantly wandering through the boat, checking valves and checking the bilges and stuff. So you stay pretty well qualified on the boat. But on a nuke, you got the forward group, you got the missile group, and then you got the nukes. And once you qualified, you didn’t really mess with the other end of the submarine. So yeah, you’re qualified, but I’m not sure if you’re qualified as well. Let’s put it that way.

Tony mentioned that it took him about one year to re-qualify on USS Lewis and Clark. Although he also said it was easier the second time around.

Tim:

[laughing] Okay. All right. So, given that a boomer’s job is to simply go out, hide, and act as a nuclear deterrent, did you notice any kind of difference in the culture of being on a ballistic missile boat versus an attack boat?

Tony:

Well, no, I didn’t because most of the guys that I was on the boat with were old diesel sailors. So they were already qualified on diesel boats. So they were pretty much the same group of guys, although, you know, I talked to a few guys on tours here. I was talking to a guy that was a diesel guy and went to a nuke after that. And he didn’t like it because he just didn’t think it was the same camaraderie. And maybe it isn’t, you know. But the group that I was with were all ex-diesel sailors. So they were, you know, this was in the transition period. This was in the early 60s. So most of the guys were diesel guys. And I ran around with more of the engineering guys than I did with anybody else on the submarine because I was a comfort net, the E-gang. So most of the guys I ran around with were nukes.

Tim:

So would you compare life being on a big boomer, very nice, you know, versus like a cramped attack boat?

Tony:

Well, this boat was really nice. This boat was nice in the fact that we very seldom had to hot bunk or anything because this boat was originally designed as a down-range missile tracking ship. OK?

Tim:

The Barbel, right?

Tony:

The Barbel was. And where the sonar room is on this ship was actually all the SINS* gear and all the stuff for tracking missiles. Well, when they flooded, they tore all that stuff out. And our sonar room was up where the crypto room is on this submarine. Our sonar room was behind [the] radio [room]. Okay. Well, they left that there because the Chiefs decided they wanted to make that room the Chief’s quarters. So we ended up with an extra set of bunks because that became the Chief’s quarters, and the Chief’s quarters on this boat was [for] senior first class. I mean, we had to have a lot of people on board the hot bunk. So we very seldom hot bunked. So I didn’t ever run across the deal of hot bunking. You know, it was a different boat compared to this boat.

*SINS: Submarine Inertial Navigation System.

Tony also told me that he slept on one of the middle racks on 2nd Street aboard Barbel and that he never hot bunked on any sub he was on.

Tim:

I see. So, how would you describe the captains on the boats you were on?

Tony:

I enjoyed all my captains. They were all very good. The first, the captain, when I went aboard the Barbel, he was a senior commander. When we hit San Diego, he left and went to the war college. And then the XO became the captain. And he was very good. I really enjoyed it. He actually became an admiral. He was a pretty sharp guy. He was nice. That’s the other thing, on the Barbel and on the Lewis and Clark, I was the captain’s phone talker. So I got involved with the captain a lot. I knew him, knew the captains quite well, because during that, during maneuvering and stuff, I was always standing behind the captain and the officer of the deck, reporting whatever they said, you know. And on this class, during battle stations, I was the captain’s phone talker. So I got along good with the captains.

Tim:

What years were you on Barbel, and what years were you on Lewis and Clark?

Tony:

I was on the Barbel from 1961 to ’63. And then I was on the Cusk for three months. October of ‘63, I went to school. So 57 weeks later, I ended up on the Lewis and Clark. So, the end of my career, the last hitch of my Navy [career] was on the Lewis and Clark.

Tim:

I see. And when did you get out of the Navy?

Tony:

I got out in 1967.

Tony technically passed the exam for Missile Technician 1st class, but left the Navy before advancing because there weren’t enough Missile Technician billets on ballistic missile subs at the time. Missile Technicians only work on ballistic missiles, and the only ballistic missiles in the Navy are on ballistic missile submarines.

Tim:

Well, moving on, what brought you to OMSI, and when did you become a Blueback tour guide?

Tony:

Well, I knew about the Blueback. I came down several times and looked at it a few times, but the job I had I traveled a lot, so I didn’t have any possibility of doing this. I ended up leaving for weeks at a time, so it wasn’t something that was a good idea for me. So when I retired in 2008, I signed up to be a tour guide.

Tim:

When you started being a tour guide, what feelings did you have walking through another B-girl boat? Did it bring back any kind of nostalgic memories for you?

Tony:

Yeah, it did. Although, like I said, this boat has gone through a lot of transitions, so things are moved around and where they would have been on the Barbel. They weren’t there, you know, so. Plus, they added stuff that, you know, that we didn’t have in the past, so like we didn’t have the prairie masking system. That was not a part of the original sub. I don’t know when they put that on here.

Tim:

So kind of how would you characterize your time at OMSI as a volunteer and a tour guide here on Blueback?

Tony:

I really enjoy this. This is a lot of fun. I enjoy talking about the different submarines, especially since I’ve been on three different classes. So, which I figure to me it’s kind of neat because I was able to go backwards and spend three months on an older boat, which is totally different. I slept in the after torpedo room on that Cusk on the way to Tahiti and was woke up in the middle of the night with this huge noise and cables running and stuff.* The after marker buoy let loose, and while we were submerged. So it’s just paling out. So we had the surface in the middle of the Pacific, and we got up on top and actually ended up, they ended up shooting it till they sunk it. Well, we’re not gonna retrieve it, try to put it back in. So they shot at it till they sunk it and then cut the cable and let it go.

*Tony mentioned he slept next to a Mark 14 torpedo.

Oh, that was a nice thing about going to Tahiti is I got to cross the equator, which was kind of a fun job. And on one of those boats, you actually surface and do it on the surface. So we crossed the equator on the surface, and they had this big garbage chute, and you had to crawl through the garbage chute and get people beat on you and kiss the belly of King Neptune and all that stuff. So it was fun. We had a swim call as well.

Tim:

All right, well, we’re coming up to the end. Is there anything else you want to say to any listeners out there?

Tony:

Not really, I don’t think. Just come on down to the Barbel [Blueback] and visit.

Tim:

Well, thank you very much for your time, Tony. Again, it’s just really unique. It’s always great having you here, having another B-girl sailor, and you bring a very unique perspective to these boats, and we’re glad to have you.

End of Transcript

Other Stories

Barbel’s 1960 Near Sinking

Regarding Tony’s story of Barbel flooding, the boat’s deck logs for 30 November 1960 show that the boat was participating in the training exercise SLAMEX while operating off Norfolk, Virginia. At 1003, flooding was reported in the engine room. The boat conducted an emergency surface, went ahead full, and rigged for collision. The engine room reported that the discharge line for the No. 1 saltwater circulating pump was “carried away.” At 1050, the boat secured from collision quarters, and at 1120, the engine room bilges were pumped dry. Due to the flooding, the following materiel casualties were reported:

- No. 2 and No. 3 main generators

- Trim pump

- Trim pump priming pump

- Trim system

- No. 1 saltwater priming pump

Thankfully, there were no personnel casualties.1 When Tony mentioned that everything above five inches had to be torn out of the boat, he meant that the piping had to be replaced since that’s what failed and caused the flooding.

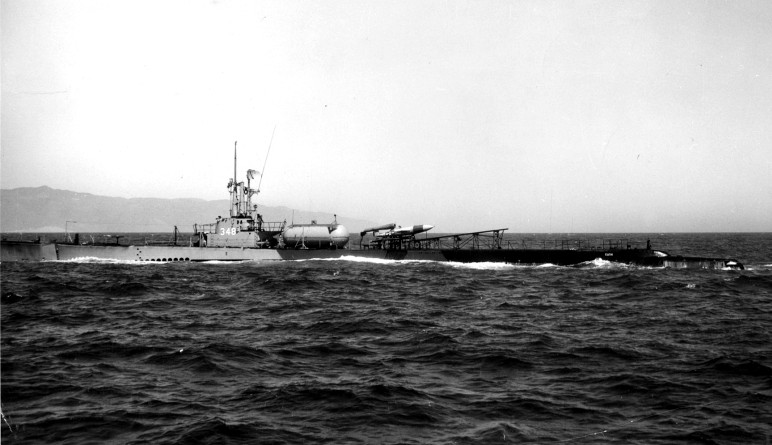

Loon Guided Missile

Tony also recounted a story of how, before his time aboard her, USS Cusk took part in the early U.S. Navy submarine missile tests. The first missiles developed for launching from submarines were American copies of the German V-1 (AKA buzz bomb). The German V-1 was a 27.5-foot-long, 4,917-pound missile with a 1,830-pound high-explosive warhead. It was launched via a steam catapult trolley from a 157-foot-long rail on land. The pulse-jet engine propelled the missile up to 400 miles per hour for 150 miles before the engine cutoff, and the missile dove toward the ground. By July 1944, the Allies had enough intelligence to begin copying the V-1; further tests designated the missile as the JB-2 by the U.S. Army and the Loon by the U.S. Navy.2 By November of 1944, Admiral King expressed interest in using these to strike land targets from escort carriers.3

U.S. Military modifications to the design included replacing the German steam catapult with a rocket booster to get the missile airborne, and the addition of radio-guidance with a radio beacon, which allowed an operator on a ship or trailing aircraft to track and course correct the missile, with the ability to steer it left, right, and dive it. The minimum operational range of the missile was specified at 100 nm with the weapon cruising at 1,000 – 6,000 ft., and the control aircraft at 10,000 – 20,000 ft. Use against land targets at 100nm involved using early warning aircraft (“Cadillac”) for control, and for use against ship targets at less than 100nm using shipborne fire control radars. Admiral King approved the large-scale program on 12 April 1945, and the Navy designated the missile as Loon on the 16th. In July 1945, an escort carrier unit commenced training off Point Mugu, California, and the first Loon was fired on 7 January 1946, but it crashed when the engine died.4

Willys-Overland built copies of the V-1, called the LTV-N-2, which were 2.8 feet in diameter and 27 feet long, with a 17.7-foot wingspan. They had a 2,000-pound warhead and a claimed Circular Error Probable (CEP) of 0.5 nm.5 While more accurate than the German V-1, the Loon had an average error of 400 m (1/4 mile) at 160 km (100 miles) range under optimal conditions.6

Plans were made for the mass production of the missile and for bombarding Japan with it from ships and nearby captured islands, but the dropping of the atomic bombs ended the war before it was deployed by the Americans.7 Postwar, plans were drawn up on 5 March 1946 and approved by Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal to convert the two fleet submarines USS Cusk (SS-348) and USS Carbonero (SS-337) to experimental launch platforms for Loon missiles. On 12 February 1947, while off the coast of Point Mugu, California, USS Cusk became the first submarine to fire a guided missile. The Loon program was cancelled in 1953. In reality, the Loon was never meant to be an operational weapon for submarines, but the tests proved valuable in training crews and gaining experience in launching missiles from submarines, particularly with the later Regulus missiles.8

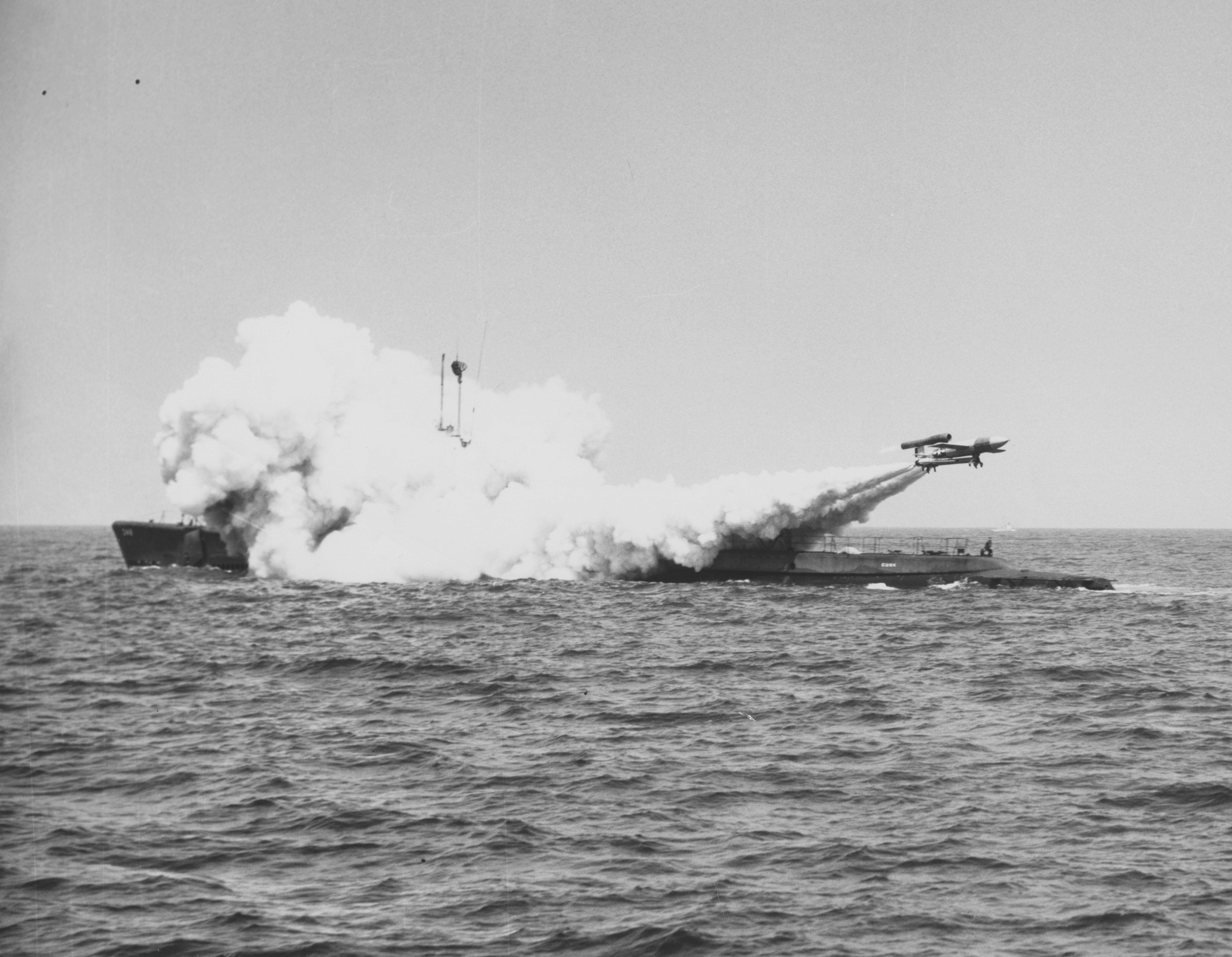

7 July 1948 Missile Explosion

Additional test firings of the Loon missile followed in the coming years, and on 7 July 1948, a unique incident occurred when Cusk fired two Loon missiles.

During the second test firing, the missile exploded and caught the deck on fire.

One sailor recalled:

Something went horribly wrong. “One of the rocket bottles exploded on the deck (of the Cusk),” recalls Thomas. “And the missile, which was full of JP-5, like kerosene, exploded and dove down on the deck of the submarine.” Horrified onlookers saw the boat disappear beneath a towering fireball and smoke cloud. “Everyone thought the Cusk had sunk,” remembers Captain Pat Murphy, USN (ret.), another Loon-era veteran. “But the Cusk‘s captain [Fred Berry] saw what happened through the periscope and saw that there was no hull rupture. Well, he submerged. They had all the water they needed to put out the fire.” The Cusk survived with minor damage.9

So there was no real cause for alarm, and Cusk turned out all right in the end.

Miscellaneous Anecdotes

Tony related a couple of other stories about USS Barbel to me. For example, Barbel once got spotted by a friendly aircraft while transiting on the surface from San Diego to Pearl Harbor, and the captain later got in trouble. While this may not seem like much of a transgression, the Barbel-class, with their teardrop-shaped hulls, were some of the first diesel-electric submarines designed for better underwater than surfaced speed.

Our examination of Blueback‘s early deck logs shows that how much time the boat spent on the surface or snorkeling depended heavily on who was the skipper. The logs show that some skippers preferred to spend most of the day snorkeling or on the surface. This is because the early skippers of the boat spent the majority of their early careers on fleet boats, which were essentially surface ships that could also dive underwater to attack or hide. The postwar GUPPY conversions of the fleet boats, particularly those that got snorkel conversions, represented a transitional period of submarine design within the U.S. Navy. This also meant that snorkeling was fairly new to U.S. submarines.

A heavy sea state also posed problems for snorkeling submarines since a wave can wash over the air induction and force the head valve in the snorkel to close. This deprives the diesel engines and the submarine of air, so the engines must be shut down to prevent creating a vacuum inside the boat and suffocating the crew. Often, a diesel-electric submarine like Blueback would just ride out heavy seas on the surface if it needed to charge its batteries. The issue is that the teardrop-shaped hull isn’t well-designed for seakeeping on the surface, so the boat would roll and pitch even in very mild swells. It wouldn’t be a comfortable ride. Some veterans of this class have told me that in heavy seas, this boat could be doing rolls of 45 degrees or more when surfaced. You’d practically be walking on the bulkheads.

Speaking of being uncomfortable, one particularly cramped space to work in on the Barbel-class boats was the battery air plenum. There’s a tiny door just outboard of the freezers that leads into the plenum to service the air filters. Tony, having recently reported aboard Barbel (as a fireman IC striker), was tasked one day with crawling through this door to do some maintenance in there. Since he was a small 5’9″, 160 lbs guy, and new to the boat, he got the duty.

Another anecdote Tony related to me was that Barbel had small jukeboxes on the outboard wall of the crew’s mess; however, they still had to insert 5 cents into them, so one of the Chiefs would keep a stash of coins so the crew could play the records when they were off watch.

USS Barbel was also on the small screen in the TV sitcom The Brady Bunch. In Season 4 Episode 1 “Hawaii Bound,” when visiting Pearl Harbor, their tour guide, David, points out two “nuclear” submarines, one of which is Barbel.

Umm…no, David. Those are both diesel-electric subs. The left picture is clearly a fleet boat and the right picture is USS Barbel. The hull number on her sail is hard to make out, but it’s 580.

An interesting story about USS Barbel, although not related to Tony’s remembrances, involves her time on the big screen. USS Barbel was decommissioned on 4 December 1989 and sent to a scrapper who removed the sail and some of the superstructure. However, what was left of the hull appeared in the 1995 Tony Scott film Crimson Tide, specifically the scene where the crew is lined up at the pier and waiting to get underway. A fake plywood sail and superstructure were placed on top of the hull, and some cosmetic changes were made to make her resemble an Ohio-class ballistic missile boat.

Now, anyone familiar with the size of an Ohio-class submarine will instantly be able to tell that what’s in that shot is definitely a different submarine because the hull is far too small. A Barbel-class submarine is 219 feet long and 29 feet wide at the beam. In contrast, an Ohio-class submarine is 560 feet long and 42 feet wide at the beam. The main giveaways in the shot are that you don’t see the hull extending much further behind the sail (when it should), and the men standing topside on deck are far too large when compared to the size of the hull itself. (Not to mention that the sail and the fairwater planes are oversized for the hull of a Barbel sub.)

Funny enough, in the very next scene, the film does show the actual USS Alabama (SSBN-731) submerging when going out to sea. Now, if the film’s trivia page on IMDb.com is to be believed, the film crew was tipped off by a civilian informant and waited outside the entrance to Pearl Harbor with boats and a helicopter to film the submarine as it left port and then submerged. While the Navy filed a complaint about filming one of its vessels without permission, it technically wasn’t an illegal act since the submarine was in public view at the time. The fact that this submarine was the actual Alabama (as in the film) was a sheer coincidence.10

As for the hull of Barbel herself, she was returned to Navy ownership and rusted away as a hulk at the pier in San Pedro until she was towed out to sea and sunk as a target on 30 January 2001 off the coast of California.11

Being a former USS Barbel sailor, Tony represents a wealth of information about this class of submarine. What’s even more unique is that he served on Barbel very early in her service, so he provides a snapshot of how these boats were operated at that time and what kind of equipment they had. In this regard, it’s interesting to compare Tony’s experiences with Rick Neault’s experiences on Bonefish and Blueback late in their service. You could ask these men the same question about this class of submarine, and you’ll potentially get two very different answers, but both will be accurate. It just goes to show that all three boats of the Barbel-class were different (since they were all built by different shipyards), and they all changed with regard to their layout and equipment as they went through various refits in drydock throughout their service. (This is generally true for all ships.)

Conclusion

Well, that was my interview with Tony Capitano, a friendly guy who loves telling stories about his time in the Navy on three different submarines. Tony can recall a lot of interesting facts about USS Barbel early on in her service and represents one of our two Barbel-class sailors. Between Tony and Rick Neault, we have all three subs in the class covered at the beginning and end of their careers. In many ways, these men represent a bygone era of submarine service in the U.S. Navy, that is, the old diesel boats. These sailors live by the adage of “DBF – Diesel Boats Forever.”12

As always, I encourage anyone to come down for a tour of USS Blueback if you’re in the Portland area. Regardless of whether it’s your first time or you’ve taken multiple tours of the boat before, we all give different tours and have different stories to tell. If you can’t take a tour, you can always donate to the museum, which goes a long way toward supporting OMSI as an institution. More information about the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), as well as USS Blueback, can be found on the museum’s website at omsi.edu. OMSI is a non-profit organization that receives support from various sources, including generous donations from people like you.

Footnotes

- “Barbel (SS-580) – November 1960,” U.S. Navy, November 1960, 213715675, U.S. National Archives. ↩︎

- Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore, Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1. ed (Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005), 86. ↩︎

- Norman Friedman, US Naval Weapons: Every Gun, Missile, Mine and Torpedo Used by the US Navy from 1883 to the Present Day, Repr (Naval Institute Pr, 1988), 216. ↩︎

- Friedman, 216. ↩︎

- Friedman, 280. ↩︎

- “Willys-Overland LTV-N-2 Loon,” accessed September 16, 2025, https://www.designation-systems.net/dusrm/app1/ltv-n-2.html. ↩︎

- Polmar and Moore, 86. ↩︎

- Polmar and Moore, 87 – 88. Polmar and Moore note that regardless of a missile’s flight or means of guidance, be it a ballistic missile or a cruise missile, the U.S. Navy referred to virtually all missiles at this time as guided, given that they could be “aimed” at a target. ↩︎

- “USS Cusk History,” accessed September 16, 2025, https://www.usscusk.com/history.htm. ↩︎

- Crimson Tide (1995) – Trivia – IMDb, n.d., accessed September 24, 2025, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0112740/trivia/. ↩︎

- “Barbel II (SS-580),” accessed September 24, 2025, http://public1.nhhcaws.local/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/barbel-ii.html. ↩︎

- In fact, the DBF pin originated in 1970 from USS Barbel sailor ETR3(SS) Leon Figurido. ↩︎

Bibliography

“Barbel (SS-580) – November 1960.” U.S. Navy, November 1960. 213715675. U.S. National Archives.

“Barbel II (SS-580).” Accessed September 24, 2025. http://public1.nhhcaws.local/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/b/barbel-ii.html.

Crimson Tide (1995) – Trivia – IMDb. n.d. Accessed September 24, 2025. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0112740/trivia/.

Polmar, Norman, and Kenneth J. Moore. Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. 1. ed. Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005.

Friedman, Norman. US Naval Weapons: Every Gun, Missile, Mine and Torpedo Used by the US Navy from 1883 to the Present Day. Repr. Naval Institute Press, 1988.

“USS Cusk History.” Accessed September 16, 2025. https://www.usscusk.com/history.htm.

“Willys-Overland LTV-N-2 Loon.” Accessed September 16, 2025. https://www.designation-systems.net/dusrm/app1/ltv-n-2.html.