Sailing Vessels as Warships

The development of sailing vessels from merchant ships into actual warships was a very slow and gradual process. By the 1400s, the three or four-masted carracks, along with the smaller and more maneuverable two to three-masted caravels, were evolving to take advantage of wind power (these designs would later evolve into galleons). In addition to being used as merchant vessels, many of the larger vessels began to mount cannons in dedicated gun ports along the hull. Even galleys in the Mediterranean began mounting guns in their bows, with smaller ones sometimes mounted between the oars (Grant, 2008, p. 10 – 11).

By the 1500s, carracks, distinguished by their high forecastles and sterncastles, were the main warships used in northern Europe. They provided a “relatively” stable platform for cannons. The largest carracks, called “great ships” could mount over 100 cannons. For example, the Henry Grace a Dieu (AKA Great Harry) in 1514, mounted some 180 guns distributed along its gun decks and high castles (Grant, 2008, p. 10). Along with the Mary Rose, these were some of the most powerful warships of their day and rendered earlier types of warships nearly obsolete (Grant, 2008, p. 75). Even then, galleys and other oared warships were still used in various parts of the world for some time.

In spite of all their impressive firepower, the attendant naval tactics had not quite developed to efficiently leverage the warship designs of the time. Naval battles during and following the Middle Ages still largely degenerated into melees with individual or small groups of ships chasing after one another, firing their guns, and possibly attempting to get close enough to board each other. Professional navies were yet to be developed with warships being largely commanded by officers with more knowledge in land warfare than in sailing. Little tactical cohesion, never mind communication, existed. Line-of-battle tactics would not come into more common practice until the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the mid-1600s.

The Eighty Years’ War (1568 – 1648) was sparked off by the Dutch revolt against the Spanish rule of the United Provinces. Eventually, the English were pulled into the war in support of the Dutch, as well as privateers operating against the Spanish in the Caribbean. Given the rather rudimentary state of naval warfare, at the time, and the lack of cohesive coordination, hit-and-run tactics were frequently utilized. English captains often used the tactic of “giving the prow” against the Spanish (Grant, 2008, p. 116 – 117).

Giving the Prow

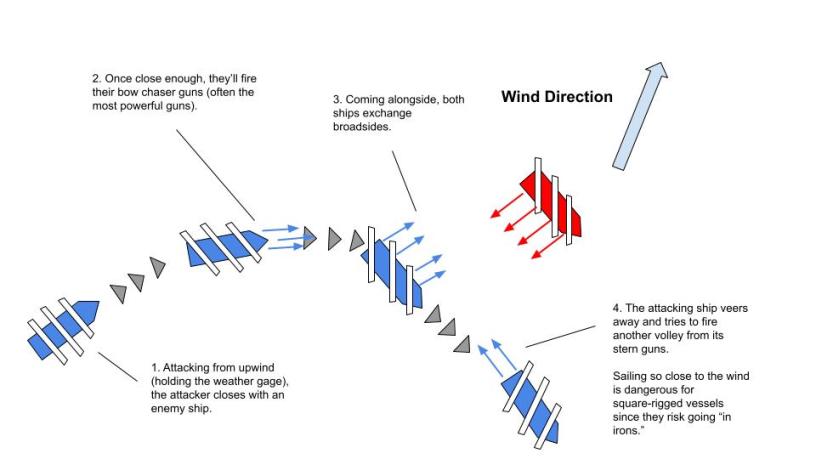

The numbers below correspond to the numbers in the above illustration.

- The premise of the tactic involves an attacking ship (blue) approaching from the windward side of an enemy vessel (red) (such a position is known as having the weather gage).

- As the blue vessel gets within range, their bow will be pointed towards the red vessel allowing blue to use the guns mounted in their bow. These bow chaser guns were often the most powerful armament on warships during this era.

- As the blue and red ships maneuver alongside each other, they would open up with their broadside guns.

- Upon passing the red vessel, blue would veer away, and possibly try to get in some final shots with their stern chaser guns. As they maneuvered away, blue would take the time to reload their guns and come around for another attack.

Advantages & Disadvantages

The advantage of giving the prow is that it allows the attacker to control the distance of the engagement by approaching from the windward side. In doing so, they are said to, “have the weather gage,” and the vessel to the lee side can’t maneuver easily or quickly to close the range and board the attacker. Should the attacker also have longer-ranged guns and better-trained gun crews, it can also allow them to keep out of range of any enemy return fire.

The main disadvantage lies in the fact that once the attacking ship veers away, they are now trying to sail into the wind. This slows them down and leaves them potentially vulnerable. It can be difficult (sometimes impossible) for square-rigged vessels to “tack” through the wind (with their bow passing through the direction of the wind). Not only do they drastically lose speed trying to sail close to the wind, but they risk going “in irons” where the wind goes out of their sails and they lose all forward way (essentially coasting to a stop with their bow into the wind). Even more drastically, at this point, the vessel can be “taken aback” when the wind pushes the sails back against the masts and the vessel can actually begin moving backward. This also puts a lot of strain on the masts. This is not to say that square-rigged ships cannot tack upwind, but it is more difficult for them to do in comparison to fore-and-aft-rigged ships. Instead, square-rigged ships often need to “wear” downwind (with their stern passing through the direction of the wind) in order to make progress upwind. This transcribes a figure-eight pattern and takes more space and time to maneuver, but it is not as risky as tacking for square-rigged ships.

In the above illustration, should the attacking vessel instead turn to port and try to sail downwind immediately after giving a broadside, they may need to pass on the opposite side of the enemy vessel which deprives them of the weather gauge and gives the enemy the advantage. Furthermore, they may also be presenting their port-side guns again which would still need to be reloaded. Thus, attempting to sail downwind immediately after attacking might not be advantageous unless the attacker put plenty of room between the enemy and themselves before maneuvering.

The Melee

Despite the disadvantages of the above tactic of “giving the prow,” a skillfully maneuvered warship could still present a serious danger to a stationary vessel even if it maneuvered around to the lee side. Thus, simply having the weather gauge did not necessarily guarantee victory, and losing the weather gauge did not portend defeat. As a melee developed, an attacking ship could likely exploit the confusion and sail in circles around an enemy. Renowned for their seamanship, the Dutch were particularly skilled at outmaneuvering their opponents in a melee (Grant, 2008, p. 127).

The above illustration shows an attacking vessel (blue) making skillful use of the weather gauge and maneuverability in a melee to close with and fire on a relatively stationary enemy vessel (red). For the sake of argument, let us assume the enemy ship is at anchor, and therefore, severely restricted in her ability to maneuver.

- The blue ship wears downwind towards a red opponent. Holding the weather gauge, they gain speed and turn to port.

- Coming alongside the red vessel’s port side, blue fires a broadside with her starboard guns with red responding with her port guns. After firing, the blue vessel turns to starboard and wears ship again. (This is in contrast to the previous tactics of “giving the prow” where the blue ship would have instead turned to port and tacked upwind at this time.)

- The blue ship reloads its starboard guns while making a wide circle around to a starboard tack. Coming alongside red’s starboard side, the blue ship fires her starboard guns again. Red’s starboard guns respond.

- After extending further away, blue turns into the wind and tacks upwind in a zig-zag pattern.

- Having gained sufficient distance to windward through tacking, blue has taken the time to reload, and can now turn to starboard. In doing so, blue can wear ship again towards red to make another attack run.

Advantages & Disadvantages

This is merely an example of a ship exploiting various factors in what would, in reality, be a confused naval brawl. As can be seen, the attacking vessel largely transcribes a circle around its opponent. This melee tactic uses the advantages of the weather gauge, speed, maneuverability, and a well-trained crew to exploit a confused situation. In this instance, it’s assumed that the opponent is largely stationary, or somehow restricted in their ability to maneuver. Additionally, the enemy vessel may be caught by surprise or have a poorly trained crew. It is easy to imagine such melee tactics failing to produce any results should the enemy vessel be equally maneuverable and with a competent crew.

Conclusion

Both tactics of “giving the prow” and exploiting maneuverability in a melee demonstrate the use of hit-and-run tactics in the days of naval warfare before the formal adoption of line-of-battle tactics. It is worth remembering that naval battles throughout history did not always follow the prescribed tactics to the letter. Additionally, naval doctrine and tactics did not always maintain pace with the technological developments of ships and weaponry. Throughout the Middle Ages and into the 16th century, naval battles still frequently devolved into melees with ships shooting at each other and attempting to close with an enemy vessel to board them. The tactic of “giving the prow” was likely one technique that attempted to leverage the growing technology of sailing ships and their cannons. It would still be some time before formalized tactics were developed.

References

Grant, R.G. (Eds.). (2008). Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare. D.K.