An occasional question we get on tours is,

Why are there two steering wheels?

Well, obviously one’s for steering left and the other is for steering right. No, I’m kidding!

I’ll aim to describe the basic operation of these controls on USS Blueback.

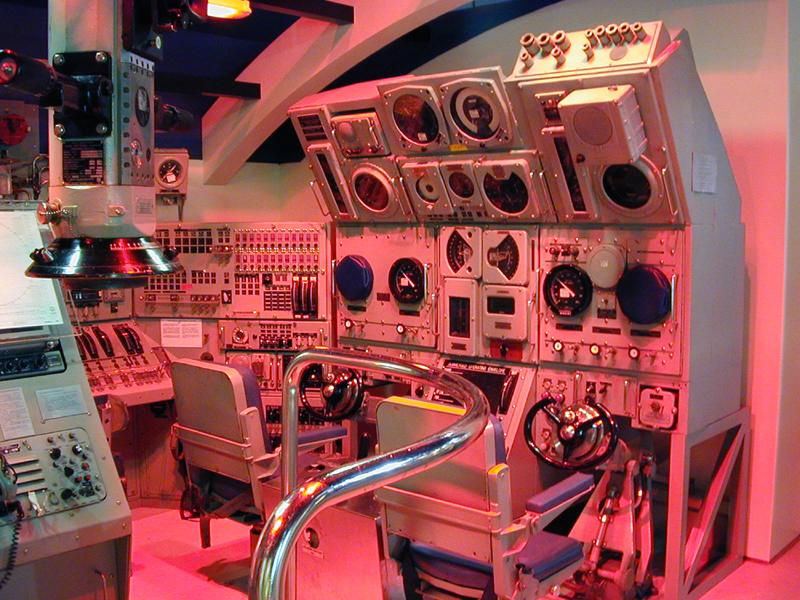

The diving station, AKA pilot station, is where the boat is steered from. Only the angle, depth, and steering are controlled from here. The propulsion of the submarine is controlled from the maneuvering room in the back. The earlier experimental research submarine, USS Albacore (AGSS-569), and the production attack subs of the Barbel-class were the first submarines to introduce aircraft-style controls for the diving station. The Barbels also introduced push-button toggle switches for ballast tank controls, as well.

The inboard chair is manned by the helmsman, who normally controls the fairwater planes and rudder. Thus, the depth and steering of the boat. The outboard chair is manned by the planesman who normally controls the stern planes, that is, the angle of the boat.

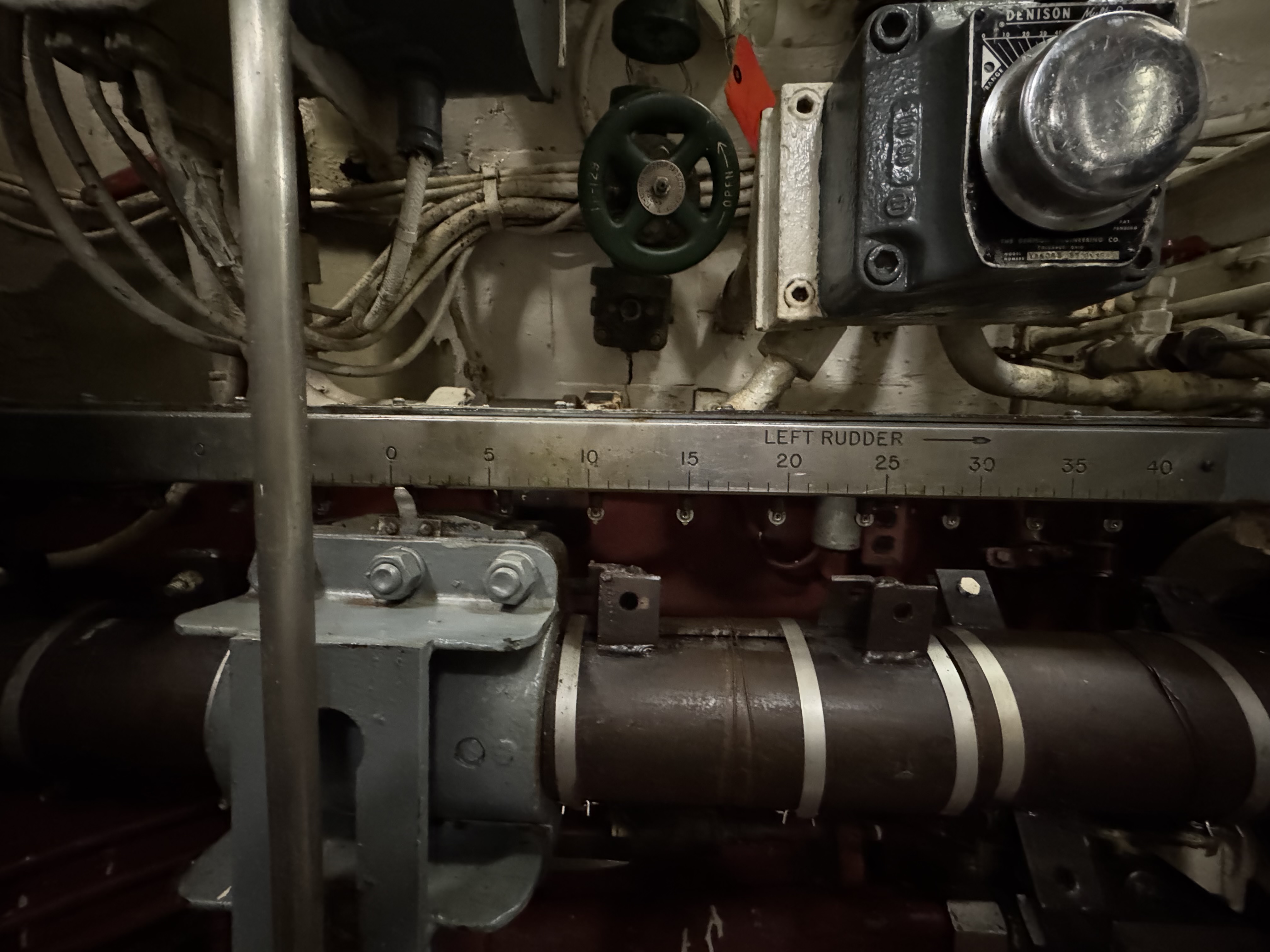

Bear in mind that we’re looking at late-1950s technology here. The system is electro-hydraulically operated. When the wheels are turned, pushed, or pulled, they actuate order servos, which transmit electrical signals to the power servos, which then port hydraulic oil to the steering and diving rams in the plane and rudder system.

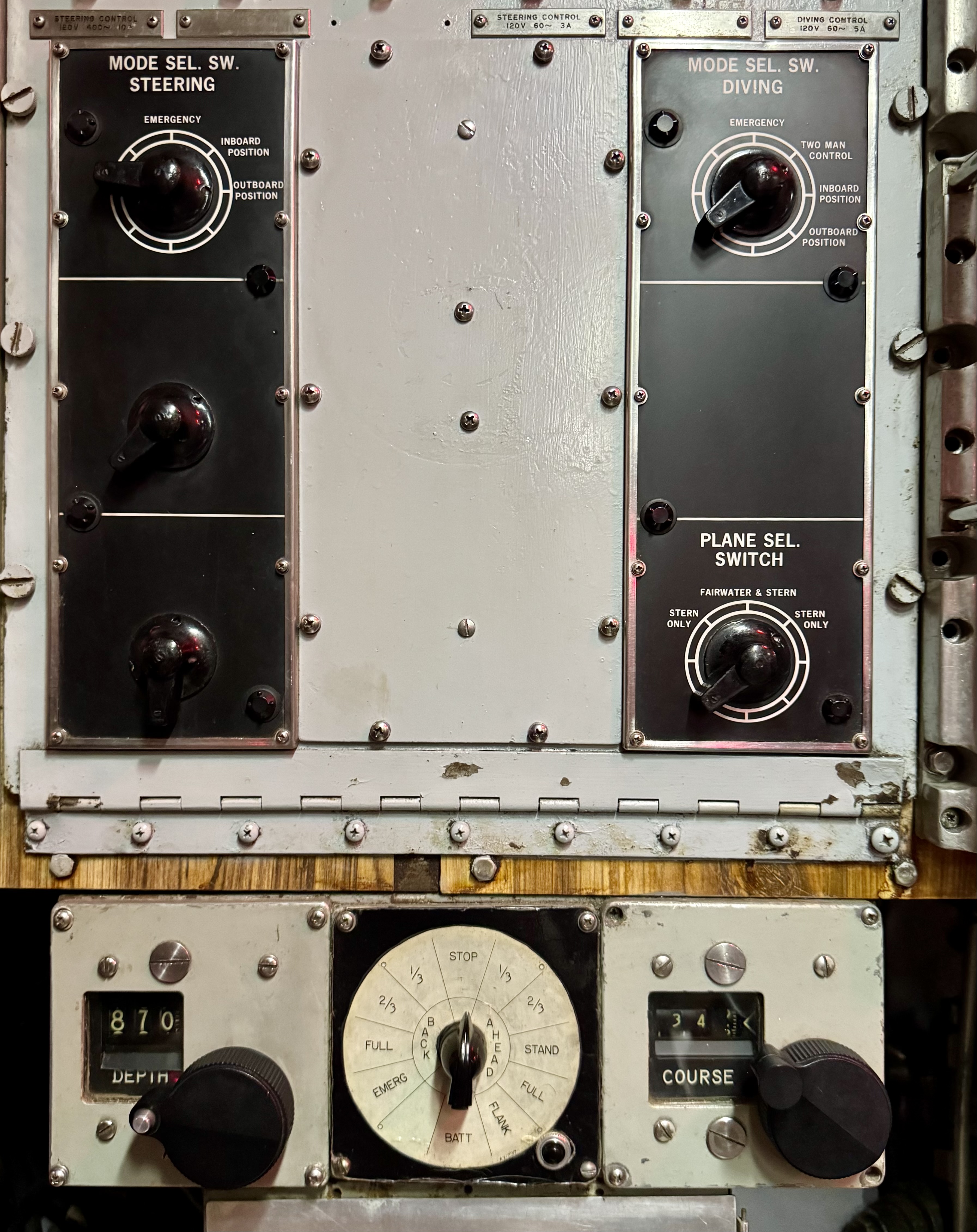

Steering and Diving

Rudder Control

The switches in the center can be used to change which station controls what function. For steering (on the upper left), the selector switch is turned to either INBOARD POSITION or OUTBOARD POSITION to change which station controls the rudder. I recall one tour guide who was describing the diving station and had this little girl on his tour ask him, “What if one person turns left and the other turns right?”

The idea being that they’re fighting over who controls the rudder.

He responded, “That can’t happen.”

Not accepting his answer, she then asked, “But what if it does?”

So he said, “Well, then the Chief of the Watch sitting behind you is gonna smack you on the back of the head and tell you to mind your helm because you’re being an idiot!”

So only one person can control the rudder at any given time.

Emergency Rudder Control

If the steering selector switch is set to EMERGENCY, then, provided that there’s still vital hydraulic power available, the Manual Auxiliary Helm (orange handle) is used to control the rudder. Effectively, this turns the system into a three-man control station.

Fairwater & Stern Planes Control

The diving selector switch (on the upper right) allows for either one or two-man control of the fairwater and stern planes.

One-Man Planes Control

For one-man control, the switch is set to either INBOARD POSITION or OUTBOARD POSITION. Below it, the plane selector switch (on the bottom right) is then set to either FAIRWATER & STERN (so the selected station controls both sets of planes) or to STERN ONLY (so the selected station only controls the stern planes). While there are two selections for STERN ONLY, there’s no difference in where the switch is set according to the electrical diagrams for the boat.

Two-Man Planes Control

When the diving selector switch is set to TWO-MAN CONTROL, the plane selector switch is bypassed, and the inboard station controls the fairwater planes and the outboard station controls the stern planes.

Emergency Planes Control

When the diving selector switch is set to EMERGENCY (provided that vital hydraulic power is available), then the planes are operated the same way as TWO-MAN CONTROL.

In the event of electrical OR main hydraulic system failure, the steering columns are operated in dive mode as in NORMAL mode, with the column linkages transmitting vital hydraulic system power directly into the rams. Vital power is passed to the emergency control valves via blocking valves, which are normally shut when energized. With the loss of electrical power (or when the switches are set to EMERGENCY), they open and allow vital hydraulic power to pass through. Similarly, the main hydraulic system blocking valves will automatically shut when there’s a loss of power. Steering in EMERGENCY mode, however, will be accomplished with the auxiliary helm.

Locking the Steering Yokes

Another feature of these wheels is that the steering columns and wheels can be locked from moving. This is accomplished by pushing a metal pin in the control columns to lock the forward and backward movement and prevent the planes from being moved up or down from here. The steering wheel itself can be locked by tightening the silver wheel. This prevents the wheel from turning left or right, and thus the rudder as well. This forms a very rudimentary kind of autopilot. If we know that we’ve set a course for a long period of time, then we can lock the wheels on a certain heading. It’s the same thing if we know we’ll be at a certain depth for a significant amount of time. We’ll lock the columns from moving the planes up or down.

A former Blueback sailor on one of my tours shared a story of how, when on watch at the stern planes, he would lean back in his chair and brace his knee against the steering yoke. Eventually, he would start to fall asleep until he heard the “pss…pss” of the valves actuating, upon which he would start awake again.

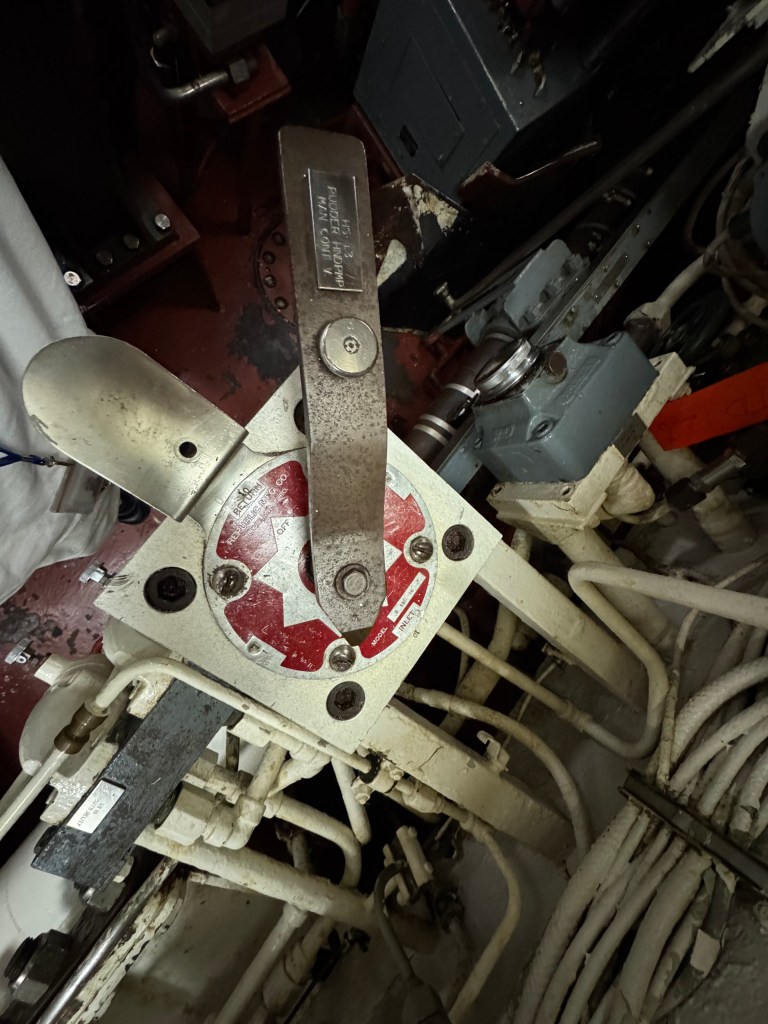

Hand Pump “Brawn” Controls

If both electrical AND hydraulic power are lost, then manual control valves and hand pumps would be used to move the control surfaces. The manual control valves for the rudder and stern planes in the Auxiliary Machinery Space (AKA Shaft Alley) would be actuated to change the direction of movement, and hand pumps would be used to manually move the rudder and stern planes.

(It has an orange bar inserted to allow a person to use it.)

A manual control valve and a hand pump in the torpedo room would similarly control the fairwater planes.

It’s also worth noting that the two planes for both the fairwater and stern, as well as the rudder, are connected. (i.e. The two planes move together, either on a rise or a dive. Left or right for the rudder. In other words, the individual planes can’t move independently of each other like ailerons on an aircraft.

Broken Artifacts

To preserve these things as artifacts, we’ve had to lock the movement of these wheels because kids on tours were treating this thing like it’s a playground, as if they were in some kind of submarine racing simulator or fighter jet. They did so many extreme turns and forward and backward movements on the steering columns that they broke. The springs inside the yokes broke, so they no longer return to center when you let them go. Similarly, anyone giving a tour down in the torpedo room would suddenly hear this loud metallic banging. That was the kids up in the control room (on another tour) violently pushing and pulling the columns all the way to the stops.

This is really unfortunate because we used to be able to do a cool diving simulation in the control room portion of the tour. The gauges on the consoles moved, and you could see the depth gauge changing as you pushed or pulled on the wheel. The tour guide would sound the dive alarm and say, “Make your depth 200 feet” or whatever. “OK, now take her to periscope depth! Make your depth 60 feet,” so they pull back and bring the depth gauge to 60 feet. Of course, we’re stationary, so you don’t actually feel any up/down angle or change in course or speed, but it was cool to pretend you were diving the submarine. Sadly, these are broken now, and the gauges don’t move, so we can’t do it anymore. Furthermore, we haven’t found any detailed documentation about the components inside these steering columns, so we’d basically have to tear the things apart and hopefully be able to figure out how to repair them. Truth be told, we probably could do it, but the main issue is the lack of time, equipment, manpower, and money. We don’t have an abundance of any of those.

We’ve also had to curtail, or completely remove, many of the more interactive parts of the tour over the years due to wear and tear on the submarine (as an exhibit) and the inability to acquire spare parts when things break. As I’ve mentioned before (but it’s worth reiterating), while museums ideologically stand for the preservation of artifacts and the education of others, the reality of museum operations is that any artifact that can be handled by people will eventually be destroyed. We’ve also had instances of people stealing artifacts from the submarine.

I recall one instance where I was on a phone call with a father whose 5-year-old kid stole something from the boat. When he found out about this, he contacted us and had his son explain himself over the phone to me. When I asked the kid why he took said artifact, his reply was, “Because I wanted it.” I ended up giving this young boy a short lecture on having integrity and not stealing things. Eventually, they mailed the artifact back. More to the point, I was just floored that a parent would hold their child accountable for their actions. You rarely see that in this day and age!

This brings me to another point, which I’ve said before, but it deserves to be repeated ad nauseam. This submarine is not a playground or an amusement park ride. If kids want a playground where they can climb over stuff and play with things, then OMSI’s science playground is on the 2nd floor for ages 0 – 6. If kids are expecting a roller coaster, then Oaks Amusement Park is just a 5-mile drive south of us. That’s where the fun rides are. The submarine doesn’t go anywhere, and it can’t go underwater anymore, because it’s a museum exhibit. However, it’s designed as a warship, it’s an industrial environment, and not something for your personal amusement. It’s very easy to injure yourself on this thing because everything is hard and made of steel. On active submarines, head injuries are somewhat common, I’ve been told. Even on Blueback, injuries happen to tour guides, even though we work here every day. I’ve fallen down ladders, cut and bruised myself, hit my head on pipes, valves, door frames, hatches, etc. Even when I’m being really careful about how I move through this boat, before I know it, I get complacent and don’t watch where I’m stepping. Then BAM! I’m not even a tall or a big guy, and it still happens to me on occasion. Now consider the fact that the tallest sailor to serve on this submarine was 6’8”!

Early attempts at digitization

Naturally, technology has advanced since Blueback was commissioned on 15 October 1959.

While the surface fleet was experimenting with the Naval Tactical Data System (NTDS) in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the submarine fleet was undertaking similar experiments with digital systems integration. Plans for streamlining information from various sources, including sonar, submarine controls, and targeting/attack systems, were tested from 1957 to 1965. The idea was to present the information of various tactical situations in a more distilled form for ease of use and to reduce strain on users. A program known as SUBIC (SUBmarine Integrated Control) was instituted by the Office of Naval Research, with Electric Boat being the prime contractor. The program was quite futuristic for the time and examined three different computer arrangements:

- A single duplex machine

- A pair of parallel computers

- A distributed network

By the 1960s, solid-state machines had become fairly reliable, and a 1963 report showed that a distributed network had a figure of merit about 1.6 times that of a single computer.1

Devices related to better dynamic submarine control were examined with a companion program called FRISCO (Fast-Reaction Submarine COntrol). This program included CONALOG (CONtact AnaLOG), SQUIRE (Submarine QUIckened REsponse), AMC (Automatic Maneuvering Control), and AUTOTAB (AUTOmatic Trim and Ballast). The CONALOG system was a CRT monitor at the diving station, which showed the helmsman/planesman the path to follow (the monitor could also display sonar and radar info). The system was installed on USS Shark (SSN-591), USS Thresher (SSN-593), and USS Permit (SSN-594) in 1961. By 1965, it was on all Sturgeon-class boats and ballistic missile subs of the Benjamin Franklin-class. While innovative for the time, the CONALOG system was maintenance-intensive and absolutely despised; so much so that by 1968, it was removed from the design of Los Angeles-class boats, which went back to analog gauges. One sub skipper reported that the CONALOG display had a tendency to put watchstanders to sleep.2 Others have also noted that the CONALOG display looks strikingly similar to the Vertical Display Indicator (VDI) screens on the Grumman F-14 Tomcat and A-6 Intruder aircraft.3

SQUIRE was a system that showed a grid display of the projected consequences of control plane movements of the boat. The vertical lines showed course, and the horizontal lines showed depth. A cross showed the boat’s actual position, a circle showed the ordered position, and a dot showed the predicted position. (I assume the idea was for the operator to align the cross, circle, and dot together in the same position on the grid.) While it didn’t show speed, it provided a 360-degree view of the submarine. A prototype was installed aboard USS Tullibee (SSN-597). A 1965 report showed that the SQUIRE system was cheaper, more reliable, and easier to use than CONALOG since it showed the user the consequences of various control actions.4

The Automatic Maneuvering Controls (AMC) installed on ballistic missile submarines was an analog computer that modeled the boat’s control characteristics. It needed to be readjusted during every refit, but it had the advantage of allowing the submarine to change depth much more smoothly than an out-of-practice planesman at the controls. This was noticeable when the crews changed over from Blue Crew to Gold Crew or vice versa.6 Friedman also notes that a submarine’s planes were most effective when travelling at or above 6 knots, known as Normal Plane Maneuvering (NPM). When below 6 knots, depth was best controlled with the planes when on an even keel, known as Even Keel Planes Maneuvering (EKPM). When below 3 knots, the boat had to rely on ballast water to change depth, known as Even Keel Ballast Maneuvering (EKBM).7

The Automatic Trim and Ballast (AUTOTAB) system was tested in 1963 and designed to control automatic hovering. It was also designed to quiet the submarine by limiting plane motion and the subsequent noise from hydrodynamic flow. Using the stern planes to correct trim angle, AUTOTAB was most effective when the submarine was making little to no forward way (as in the case of firing missiles).8

There were various other components to these attempts at early digital integration of a submarine’s systems, but they’re related to fire control, so I won’t discuss them in this post.

However, the automation of submarine systems isn’t new and has been attempted by other nations. The famed (and feared) Soviet/Russian Alfa-class (Project 705) submarines had crews of only around 30 men (24 officers, 4 warrant officers, and 1 petty officer (a cook)). The Alfas were the first submarines to integrate all facets of navigation, tactical maneuvering, and weapons employment into a single combat system, which provided the captain with the optimum recommendation for making a decision. Additionally, all of the functions for ship control, propulsion, weapons, sensors, and communication were handled from the control room. Aside from the living spaces, all other compartments (e.g. torpedo or engineering) had no permanent watchstanders and were only entered for maintenance or occasional repair work.9 While the small crew size was unique, the designers at Malachite noted that the heavy automation presented problems since the systems were so complex; reliability became an issue. Operational experience with the Alfa-class also demonstrated that the small crew size meant there were fewer people available in the event of emergencies, to repair broken systems at sea, or to replace any ill or injured crew. There was also the need to train highly skilled crewmen, provide for their replacement, and promote the officers. In retrospect, Radiy Shmakov of Malachite said that the Alfas were a “design project of the 21st Century” and many years ahead of their time. But they turned out to be too difficult to effectively operate.10 This was likely due to the immaturity of the technology at the time.

Modern Submarines

On U.S. submarines, automatic controls didn’t end with AMC, as described above. In fact, in 1977, Rockwell’s Autonetics Aided Display Submarine Control System (ADSCS) was tested aboard USS Los Angeles (SSN-688) during a Mediterranean deployment. With this system, the boat’s course, depth, turning-rate limit, depth-rate limit, and bandwidth could be input and executed with a button press. For example, they could order the boat to go to periscope depth, plus or minus one foot, with a high depth rate. This also quieted the submarine by reducing plane motion at high speed and reducing hydraulic noise. While it was never adopted, Norman Friedman speculates that it inspired the computer-piloting system used on USS Seawolf (SSN-21).11 ADSCS had a follow-the-pointer system that showed a point of light on the edge of the rudder and diving plane angle indicators for the helmsman and planesman to follow. The whole system was driven by the UYK-20 computer. While the test of the ADSCS was successful, the Navy declined to buy it. Friedman cites an article in the January 1989 periodical Submarine Review by A.J. Giddings, who opines that the submarine force had a mentality that made it averse to automatic control.12 Ultimately, the Los Angeles-class submarines not only did away with CONALOG, as described above, but also completely removed automatic controls for steering, diving, and hovering.13

Seawolf-class boats show a red and black digital display in front instead of the traditional dials and gauges. But they still have these aircraft-style wheels and analog gauges above the screens. As mentioned above, based on Friedman’s research, the Seawolf boats may also have some form of automatic controls as well.

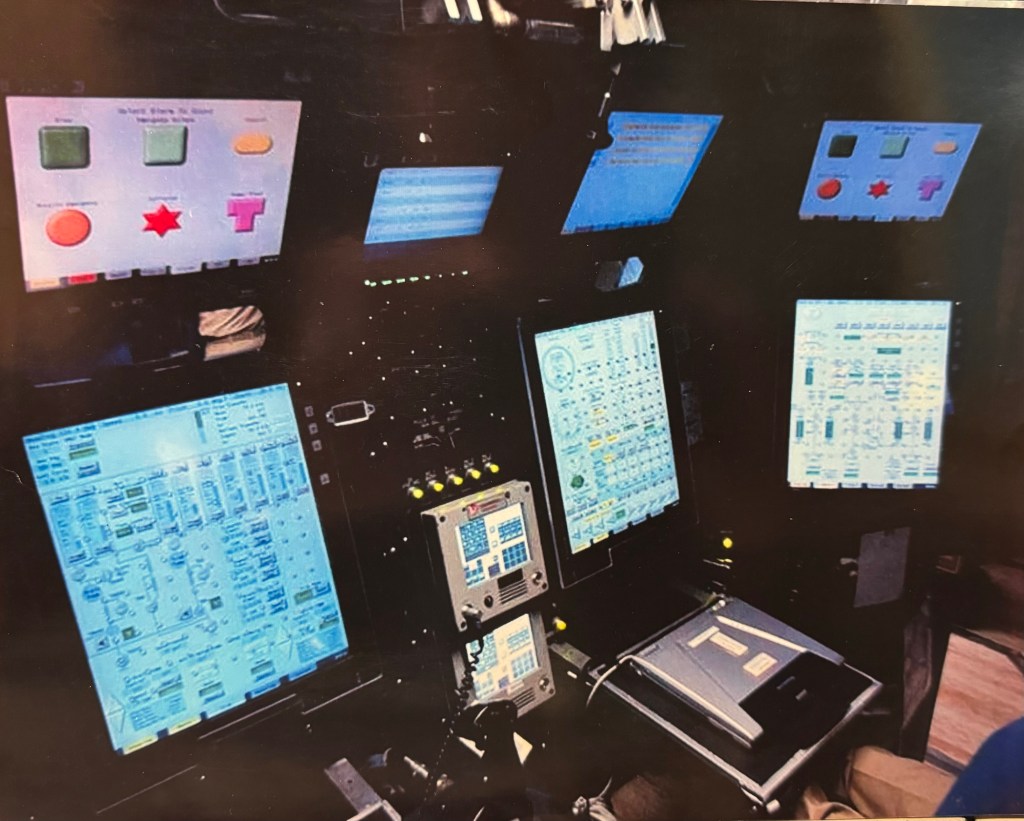

On a modern Virginia-class attack boat, it’s all digital. The entire control room is covered in large flat touchscreens in lieu of analog dials and gauges, and what’s displayed on these screens can be changed depending on the need. Similarly, there are multiple flat touchscreens at the pilot station, a joystick for each of the pilots, and a laptop computer in front of them. Fiber-optic fly-by-wire controls have replaced the electro-hydraulic controls of older boats, and there’s no separate need for helm and plane controls since the submarine is essentially “flown” underwater.14 One of our volunteer tour guides who served on a Virginia-class boat said they hardly ever used the joysticks to control the boat (although they could if needed). So when the pilots are given an order, they’d just punch in the appropriate information like course, depth, angle, etc., then hit enter, and the submarine would automatically maneuver. Effectively, it’s become something out of the TV show Star Trek!

Anyway, things have obviously changed with submarine controls since the 1950s and Blueback‘s day. What’s surprising is that it took so long for submarines to adopt more digitization and automation of their controls. Then again, history shows that the U.S. Navy submarine force has resisted automation in its boats, especially when compared to the Soviets/Russians, who tried with the Alfa boats, but with varying degrees of success. Nowadays, this amount of automation is much more commonplace as technology has matured rapidly with digital technology.

Notes

- Norman Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945: An Illustrated Design History, Revised edition. Printed case edition, with Jim Christley (Naval Institute Press, 2023), 115 – 116. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 117. ↩︎

- Tyler Rogoway, “Check Out This Mystery Navigation Screen Mounted In The Conn Of A Sturgeon Class Nuke Sub,” The War Zone, December 6, 2018, https://www.twz.com/25349/check-out-this-vintage-mystery-navigation-screen-in-the-conn-of-a-sturgeon-class-nuke-sub. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 117 – 118. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 118. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 118. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 284. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 118. ↩︎

- Norman Polmar and Kenneth J. Moore, Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1. ed (Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005), 140. ↩︎

- Polmar and Moore, Cold War Submarines, 144. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 118. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 284. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 167. ↩︎

- Friedman, U.S. Submarines since 1945, 222. ↩︎

Bibliography

Friedman, Norman. U.S. Submarines since 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Revised edition. Printed case edition. With Jim Christley. Naval Institute Press, 2023.

Polmar, Norman, and Kenneth J. Moore. Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines. 1. ed. Dulles, Va.: Potomac Books, 2005.

Rogoway, Tyler. “Check Out This Mystery Navigation Screen Mounted In The Conn Of A Sturgeon Class Nuke Sub.” The War Zone, December 6, 2018. https://www.twz.com/25349/check-out-this-vintage-mystery-navigation-screen-in-the-conn-of-a-sturgeon-class-nuke-sub.

Tim, thank you for such a comprehensive and interesting post. Having sailed on carriers, it was all new to me. Looking forward to other posts!

LikeLike