Comparisons between the various military forces of the world, be they land, naval, or air forces, are nothing new or even original. In fact, our assessments of foreign military forces are heavily dependent on our intelligence picture of what the other side possesses and what we believe their capabilities to be. Of course, not all military forces are the same size, nor do they possess the same capabilities. With regard to naval forces, the number and size of the vessels may or may not be the most reliable indicator of what a navy can do. Among the discussions of how navies exercise their power, one of the topics frequently brought up is how inferior navies can operate as a fleet-in-being to leverage their strategic, operational, or tactical position for an advantage. The first step will be to define what a fleet-in-being is. After doing so, the discussion will move through several examples of how fleet-in-beings were used throughout history and end with an examination of possible options for a fleet-in-being. Ultimately, it can be seen that a fleet-in-being is not merely a moniker for an inferior navy, but a range of strategies that a smaller navy can use to combat a superior navy given the appropriate set of circumstances.

What is a Fleet-in-Being?

A “fleet-in-being” is usually spoken of in reference to a smaller or weaker naval power attempting to wrest control of the sea from a more powerful foe. The term itself hinges on there being a large enough disparity in power between at least two naval forces with the weaker force being the “fleet-in-being.” According to Ian Speller (2014), achieving a decisive victory at sea requires a force that is numerically superior and/or more efficient in combat. That said, such a superiority in force usually deters a weaker enemy from attacking, and with no fixed points at sea to defend, it can be difficult to force an inferior opponent to fight. Thus, a weaker navy may simply opt to stay in port and defend its position. The mere presence of this weaker fleet operates on the assumption that it would strategically restrict a superior enemy’s choices and serve its purpose without achieving command of the sea (49). In other words, simply by being there, a smaller fleet can still present a potential threat.

Additional nuances to the term exist, as well. Geoffrey Till (2013) writes that a fleet-in-being is a defensive strategy (of several strategies) for attaining command of the sea, where the strategic advantage is created by a fleet that is not willing to engage a superior adversary in battle. Furthermore, weaker navies have a preoccupation with outflanking or limiting a stronger adversary’s ability to command the sea. Like decisive battles or blockades, operating as a fleet-in-being occurs at the tactical and operational levels of war (p. 157). Furthermore, the fleet-in-being strategy aims to reduce a superior opponent’s strategic ability to command the sea (Till, 2013, p. 172 – 173). Additionally, French Admiral Raoul Castex opines that even superior naval forces can be forced into limited defensive operations by circumstances, such as pursuing offensive operations elsewhere. In essence, all navies face the issue of making the best use of limited resources when confronting a superior navy (as cited in Till, 2013, p. 173). What we gain from these definitions and theorists is that a fleet-in-being is both the physical presence of an inferior fleet and a defensive strategy to be used.

Early Examples

In 1690, British Admiral Arthur Herbert (1st Earl of Torrington) faced a superior French fleet, under Admiral Anne-Hilarion de Tourville, in the English Channel. Believing that the presence of his force posed an unacceptable risk to the French and would ultimately accomplish his goal of preventing an invasion of England, he declined to give battle. Unfortunately, he was overruled by Queen Mary and forced to engage the French. The resulting Battle of Beachy Head ended in a British defeat and a court-martial for Torrington. Thankfully, the French failed to exploit their victory (Speller, 2014, p. 49).

This is also reportedly where the term “fleet-in-being” came from. Prior to the battle, Torrington wrote:

…whilst we observe the French, they can make no attempt either on sea or shore, but with great disadvantage… Most men were in fear that the French would invade; but I was always in another opinion: for I always said, that whilst we had a fleet in being, they would not dare to make an attempt.

(as cited in Till, 2013, p. 174)

While the British government eventually accepted Torrington’s actions, which dissuaded the French from invading, it appears that they were expecting a more decisive engagement and Torrington never commanded a force at sea again. Torrington’s critics note that his success was largely due to de Tourville’s failure to follow up on his victory with a pursuit. Instead, de Tourville carried out an inconsequential raid at Teignmouth (Till, 2015, p. 174).

Giuseppe Fioravanzo (1979) identifies the French naval operations in the Indian Ocean, specifically the battles of Coromandel and Ceylon (AKA battles of Sadras and Providien) in February and April of 1782, as illustrative examples of a naval force operating as a fleet-in-being. While both battles featured relatively equal numbers of ships in the opposing forces, Admiral Pierre Suffren managed to tactically defeat the British forces under Edward Hughes and force them to retreat both times. While Suffren has been criticized for not following up and pursuing the English, Fioravanzo observes that Suffren’s mission was to secure the French lines of communication in the Indian Ocean. Being far from home and with limited forces that couldn’t be quickly reinforced, it wouldn’t have benefited him to fight a large or decisive engagement. Thus, these operations stand as a good example of a fleet-in-being, but on the high seas rather than in a port (p. 91 – 93).

WWI and WWII

Geoffrey Till (2015) observes that the German Navy stands as an example of the strategic gains that can be obtained by using a fleet-in-being or a defensive naval strategy. He notes that Admiral Tirpitz’s Naval Law of 1900 embraced the concept of “Risk Theory” which posited that the German Fleet would present such a danger to the larger Royal Navy that could not let its guard down and would feel further exposed to other threats. Consequently, the German fleet-in-being would deter the British from pursuing policies that would obstruct German interests. Unfortunately for Germany, Britain settled its differences with these “other threats” (France and Russia) which allowed it to focus on the German Fleet and the German “Risk Theory” strategy ultimately failed. However, it was an attempt at using an inferior naval force to exert indirect political pressures (p. 175).

During WWI, the German Navy was too strong for the Royal Navy to impose a close blockade. Instead, they opted for a distant blockade which allowed the Germans limited use of the North Sea. This further created opportunities for the German surface raiders and U-boats to sink merchant shipping. German fleet operations aimed at gradually weakening the superior Royal Navy until the odds were more acceptable for a battle. The Battle of Jutland was an attempt at putting these concepts to work, but neither the battle nor the operational plans panned out. Even so, the British need to maintain a blockade forced them to be in a state of constant readiness and they would have little warning should the German Fleet have sortied again. The British destroyers were also tied up with the Grand Fleet which meant they could not be used as escorts for other shipping. Admiral Scheer opined that the continued existence of the German High Seas Fleet kept the British Royal Navy far to the north and they did not risk attacking the German coast or the U-boats at their source (Till, 2015, p. 175 – 176). Not everyone in the Royal Navy held a high opinion of the British strategy, and Captain Bernard Acworth opined that the Royal Navy had adopted an overly cautious approach as its doctrine. He concluded that the German defensive strategy, and defensive strategies in general, were only effective when the stronger navy allowed them to be (Till, 2015, p. 177).

During WWII, the German Navy tried a more passive approach with Admiral Raeder specifying that naval forces would only attack if it would help to achieve the navy’s main objective. He also specified frequently changing the operational areas of naval forces to create confusion with the enemy. In another example, the battleship Tirpitz was deployed to Norway and forced the British to devote significant resources to defending the supply convoys to Russia. The hassle this battleship caused the Allies was far beyond its actual capacity (Till, 2015, p. 176). In the Pacific, U.S. carrier forces adopted an active fleet-in-being approach in 1942 against the Japanese. For example, prior to the Battle of Midway, Admiral King’s instructions to Admiral Nimitz were to use attrition tactics and not get drawn into a decisive engagement that would result in the loss of the carriers and cruisers. The continual hit-and-run tactics of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific bought them time to build up their fleet before going on the offensive. Thus, it stands as another example of a successful active fleet-in-being strategy that is more viable than passively sitting in a port or committing to a suicidal engagement as the German Navy was supposedly planning at the end of WWI (Till, 2015, p. 177).

Wayne Hughes and Robert Girrier (2018) write that ports have traditionally been a (mostly) safe haven for fleets. However, by WWII, this measure of protection had disappeared. The British air raid on the Italian fleet at Taranto in November of 1940 and the famous Japanese raid on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 demonstrated the vulnerability of ports early in the conflict. Later U.S. carrier raids on Rabaul in 1943 forced the Japanese to withdraw to Truk which would later be raided in February 1944. Eventually, the U.S. Navy could concentrate a tremendous amount of air power against any island in the Pacific. This forced the Japanese to completely retreat into the Western Pacific where they were pushed back to their home islands (p. 184).

As a Modern Strategy

Historically, the stronger navy dealt with a weaker navy’s fleet-in-being strategy by implementing a fleet blockade. The objective of the blockade would be to prevent the weaker navy from interfering with the superior navy’s ability to use the sea. Mahan argued that a fleet blockade at a decisive point near the enemy’s main fleet bases was more effective than dispersing the fleet to protect other maritime interests directly. A direct fleet blockade also had the added benefit of knowing exactly where the enemy was located. Another advantage would be that a fleet blockade would prevent dispersed enemy forces from concentrating (Till, 2015, p. 178 – 179).

Speller (2014) writes that with the capabilities of modern Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) and precision strikes, it is debatable as to whether or not a fleet in being is still a viable approach for a navy. Hiding in a harbor behind a minefield may no longer keep a fleet safe from attack unless air superiority is established along with defenses against cruise and ballistic missiles. The fleet will have to be well-protected or well-hidden. Even so, the fleet-in-being strategy has been used in modern times, for example, with the Argentine Navy during the Falklands War in 1982. It may also be possible to retain an inferior fleet by having it be interned by a friendly or neutral country (p. 101). Along similar lines, Hughes and Girrier (2018) opine that maintaining a fleet-in-being would be more difficult in modern times given the current capabilities of weapons. However, it may not yet be obsolete (p. 231).

What are the Options for an Inferior Fleet?

Clausewitz wrote that the decision for war originates with the defense, not with the aggressor; the ultimate object of the aggressor is possession, not fighting (as cited in Hughes & Girrier, 2018, p. 231). Hughes and Girrier (2018) write that Clausewitz’s saying applies to naval warfare, as well. In theory, the main objective of a fleet is the destruction of the enemy’s fleet in a decisive battle. The strategic premise is that the destruction of the enemy fleet creates more options. In practice, the decisive battle rarely occurs unless both sides choose to fight, and history has many examples of one side avoiding a decisive battle. This helps explain why there have been so few battles at sea (compared to on land). Along this line of thinking, an inferior naval force will only want to fight when the opposing force is at a disadvantage in the pursuit of its operational objectives. The goal of naval operations is generally that of either sea control or power projection. Sea control is aimed at protecting sea lines of communication and focuses on destroying enemy forces that threaten those lines. Power projection employs sea control by using strikes ashore or amphibious landings. With that in mind, a strategy should never overburden a tactician with too many objectives, as this can be exploited by an inferior force (p. 231 – 232).

Hughes and Girrier (2018) theorize that an inferior navy has several options, but all with the ultimate objective of naval forces influencing events on land:

- Defense by fleet action will fail.

- The consequent option would be to maintain a fleet-in-being much like the German High Seas Fleet did after the Battle of Jutland or the French Navy did during the Napoleonic era. The downside to this option is that the competence of the fleet-in-being with degrade due to their inaction, and the superior navy will be able to take greater risks to command the sea.

- Whittle down the enemy to more fair odds in a decisive battle.

- This was the strategy of the German High Seas Fleet prior to Jutland, and the Imperial Japanese Navy prior to World War II. The High Seas Fleet utilized deception and trickery to their advantage in smaller battles, and such a strategy of gradually depleting the enemy was also envisioned by the Japanese Navy as preceding a decisive engagement. To that end, the Japanese Navy developed suitable tactics (e.g. night fighting and destroyer torpedo attacks) which they used to their advantage in early battles when they enjoyed superiority.

- When the ratio of forces is favorable to the smaller fleet, they can surprise the enemy in a vulnerable time and exploit it to gain command of the sea.

- The inferior navy cannot plan based on enemy capabilities, but instead, it must take calculated risks based on its estimation of the enemy’s intentions. For example, the Americans were outnumbered at the Battle of Midway, but Admiral Nimitz ordered the use of calculated risk based on good intelligence that allowed the Americans to seize the initiative, achieve surprise, and attack effectively first.

- Establish local superiority.

- During WWII, the Germans were able to accomplish this in the Baltic. The Italian Navy and Air Force were also able to (at times) in the Mediterranean.

- Sea Denial by creating a vast no man’s land.

- For a continental power, it may be enough to deny the coast to the enemy since it already has a purpose on its own land. German U-boat campaigns in both world wars are an example of sea denial in pursuit of continental objectives. In the Mediterranean Theater, British naval and air operations against Rommel’s sea lines of communication serve as another example of hindering his objectives on land. Post-WWII, the crux of the Soviet naval strategy against NATO and the U.S. Navy was long-distance sea denial by air and submarine. If a sea denial strategy fails to win the war, it can still be useful in providing operational leverage. For example, the Allies dedicated enormous costs and resources to combat the German U-boat threat. In the Pacific, the Japanese kamikazes could not restore command of the sea, but they tried to delay or cripple the U.S. Navy as they approached Japan. Today, coastal defenses, which would be no threat on the high seas, could seriously damage a fleet as it operates in the littorals.

- Achieving maritime objectives through events on land.

- For a continental power, they may be able to alter maritime objectives by events on land. During WWI, Britain’s Expeditionary Force suffered heavily but helped to protect France so it was not overrun by the Germans. Therefore, Germany (a continental power) was forced to base its fleet and U-boats in the North Sea. In WWII, after France was occupied, the Germans could deploy their U-boats from the Bay of Biscay. Furthermore, had Hitler chosen, aircraft from French airfields could have also devastated Allied shipping. Thus, events on the ground during the Fall of France made Royal Navy operations extremely precarious and nearly defeated Britain’s maritime strategy. These serve as further examples that sea power has a far slower and more indirect influence on events on land than many realize.

(p. 237 – 239).

Relating to the tactical aspects of the above missions, Hughes and Girrier (2018) write that naval commanders must be particularly cognizant of the role that sea forces have in influencing events on land. This is because it is anticipated that the two domains will be even more connected in the future. In addition, any future enemy will likely have a far more land-oriented posture in terms of its naval organization and doctrine. Lastly, Mahanian naval doctrine has caused us to focus too heavily on the decisive battle and neglect the importance of applying naval power on land and in the littorals (p. 240).

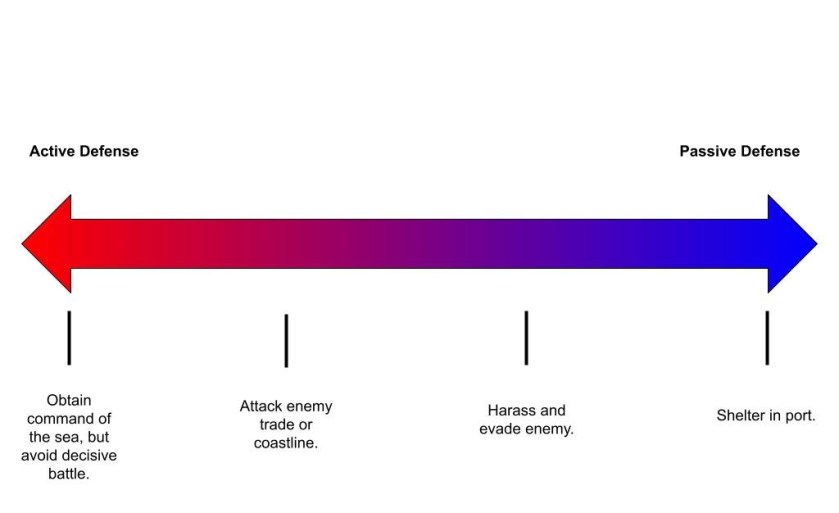

Geoffrey Till (2013) puts the fleet-in-being strategy on a spectrum with a moderated offensive on one end and a passive defense on the other. The environments range from littoral waters to the high seas, and for both short and long time periods. In their various forms, an inferior fleet’s operations can aim to:

- Obtain command of the sea, but avoid forcing the issue through battle. Alternatively, they can engage in a raiding campaign designed to wear down the enemy’s superior strength.

- Create a positive strategic outcome without trying to defeat the other side’s forces (e.g. attacking an enemy’s trade or coastline).

- Create a negative outcome by prohibiting a stronger enemy to exercise their superiority (perhaps through harassment and evasion).

- Merely ensure the continued survival of the weaker fleet.

(p. 173)

Modeled graphically, a fleet-in-beings spectrum of options might look something like this:

Julian Corbett theorized that the full potential of a navy operating on the defensive, while not securing command of the sea, could strategically allow for more time in the long run and prevent the superior force from attaining command of the sea. That being said, he also noted that such defensive campaigns need to be conducted very imaginatively and that it is not enough to merely keep the fleet in existence. Additionally, Corbett thought that a defensive strategy was not the opposite of an offensive one. In fact, it could serve as a complement. By exercising a defensive strategy in one area, a navy could create an opening for an offensive strategy in another area (Till, 2015, p. 174).

Till (2015) further compares a fleet-in-being strategy to guerilla warfare and notes that Mahan and Castex had similar opinions on a fleet-in-being pursuing a more active strategy. Rather than allowing the navy to waste away in a port, Mahan opined that weaker navies should keep their forces together and make infrequent appearances, bolstered by rumors to increase anxiety in the enemy. By being elusive, the enemy would be forced to detach forces from the main body which would otherwise weaken the main force and could allow for individually separated enemy forces to be defeated in detail. Castex had a similar idea linked to harassing the enemy when given the opportunity (p. 174 – 175).

In the end, Till (2015) identifies the following seven components that underlie and successful defensive/fleet-in-being strategy:

- Base and logistic security

- Divided enemy forces

- Helpful geography

- An effective campaign plan

- Sufficient air and sea capabilities

- Superior domain awareness

- Delegated command and control

Till notes that maintaining the physical security of your forces while exploiting superior domain awareness to force the enemy to disperse their forces is critical. In a limited war supported by a political strategy, a campaign involving deception, avoidance, and hit-and-run tactics can be effective against a superior enemy (p. 177 – 178).

In summation, a fleet-in-being is not only another term for a smaller or weaker navy but an entire defensive strategy that can be executed to achieve some outcome. Through a variety of means such as harassment of a superior enemy’s forces and coastline, raiding enemy commerce, or simply staying in port and presenting a potential threat, the range of options for a fleet-in-being spans a spectrum from active to passive defense. While an inferior fleet cannot win in a straight-up decisive engagement with a more powerful fleet, they can adopt a more defensive strategy to buy themselves time and disrupt the superior enemy’s ability to carry out its objectives at sea and/or on land. Of the many ways to carry out such a defensive strategy, the successful implementation of a fleet-in-being arguably hinges on leveraging a well-thought-out political strategy with effective domain awareness and logistical security that allows for the survival of an inferior force while simultaneously dividing superior enemy forces. It must also be considered that local superiority may be achievable and that a navy’s objectives may also be accomplished on land given that naval operations are almost always tied to some purpose ashore.

References

Fioravanzo, G. (1979). A History of Naval Tactical Thought (A.W. Holst, Trans.). Naval Institute Press.

Hughes, W. P. & Girrier, R.P. (2018). Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations (3rd Ed.). Naval Institute Press.

Speller, I. (2014). Understanding Naval Warfare. Routledge.

Till, G. (2013). Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-First Century (3rd ed.). Routledge.